Features

Recommended

Popular

10 MIN READ

As more Nepalis learn Mandarin, Chinese students are also learning Nepali, providing an opportunity to develop people-to-people relations between the two neighbors.

It was 1960 when Zeng Xuyong, fresh out of high school, was instructed by then Chinese Premier Zhou Enlai to study the Nepali language. Three years into his study, Zeng would be called upon to receive the first delegation from the Nepali Parliament led by Bishwa Bandhu Thapa after the establishment of Sino-Nepal diplomatic relations.

Zeng would go on to serve as the Nepali translator on official visits by King Mahendra and King Birendra to China, as well as accompany every high-level Chinese visit to Nepal – from Zhou Enlai to Li Xiannian, former president of China. With his proficiency in Nepali and years of experience in diplomacy, Zeng eventually became Chinese ambassador to Nepal in 1998.

China’s far-sighted decision to train a batch of Chinese students in the Nepali language hinted at a genuine interest and willingness to understand its southern neighbor. This inclination continues to date.

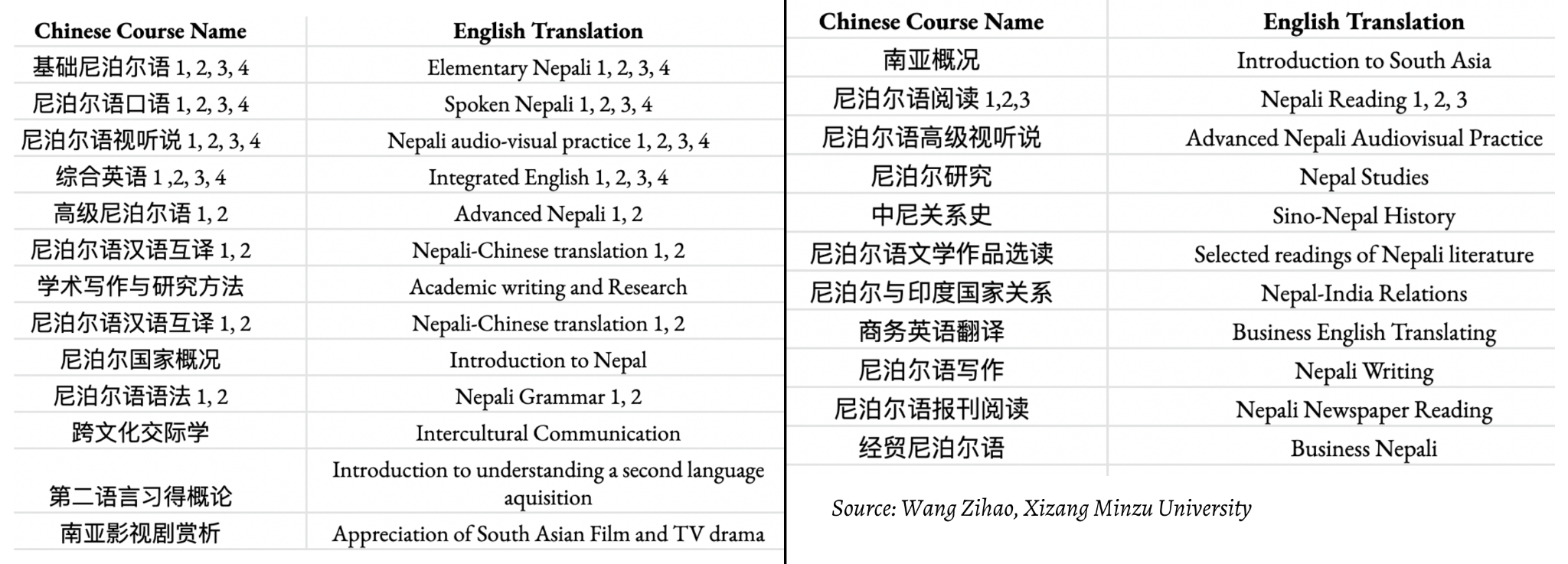

Currently, there are five Chinese universities – Communications University of China, Beijing Foreign Language University, Yunnan Minzu University, Xizang Minzu University, and Yunnan University – that offer Nepali as a major in their undergraduate degree programs. While Yunnan University has yet to enroll any students into this major, the others already have a number of graduates who’ve studied about four years of Nepali. However, the total number of students from all four universities won’t even add up to 100 students a year, according to those who are currently studying Nepali.

First impressions

Despite over half a century of diplomatic relations, most Chinese nationals still consider Nepal “mysterious”. That perception, however, is slowly changing as the Chinese are now learning about Nepal in many different ways, aside from their geography and history classes.

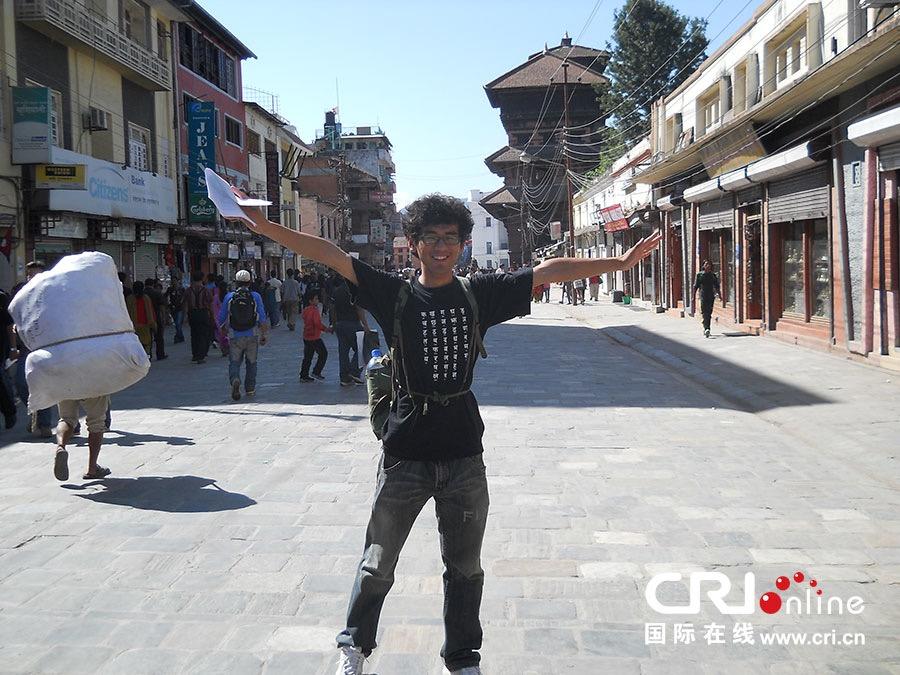

Zhang Hao, ‘Ambar’, majored in Nepali at Communications University of China. He now teaches Nepali at Foreign Language University.

“I first learned about Nepal while playing a Chinese video game similar to Counter-Strike (CS) named CrossFire in elementary school, where one of the in-game weapon options was a khukuri, also known as “尼泊尔军刀” (Nepali military knife) in Chinese. I remember it was quite a popular choice for many young Chinese boys due its handsome appearance,” said Ambar.

Similarly, for Du Wenlong, ‘Bijaya’, a graduate student and Nepali language translator at the International Department of the Communist Party of China, it was the 2014 Chinese movie, Up in the Wind (等风来), which was shot mostly in Pokhara and Kathmandu, that made up his first impressions of Nepal.

“Nepal was a mystery I wanted to explore. Its snow-capped mountains and lakes, as well as its architecture, awoke the wanderlust in me,” he said.

Another student, Guo Yunjiao, ‘Jenisha’, a final year Nepali language student at Beijing Foreign Language University, learned about Nepal from a travel memoir, Blue Heaven (蓝色天堂), written by Bi Shumin.

It is worth noting here that all sources of information about Nepal are in the Chinese language and are overseen by the state, which conveniently allows the government to manage public opinion.

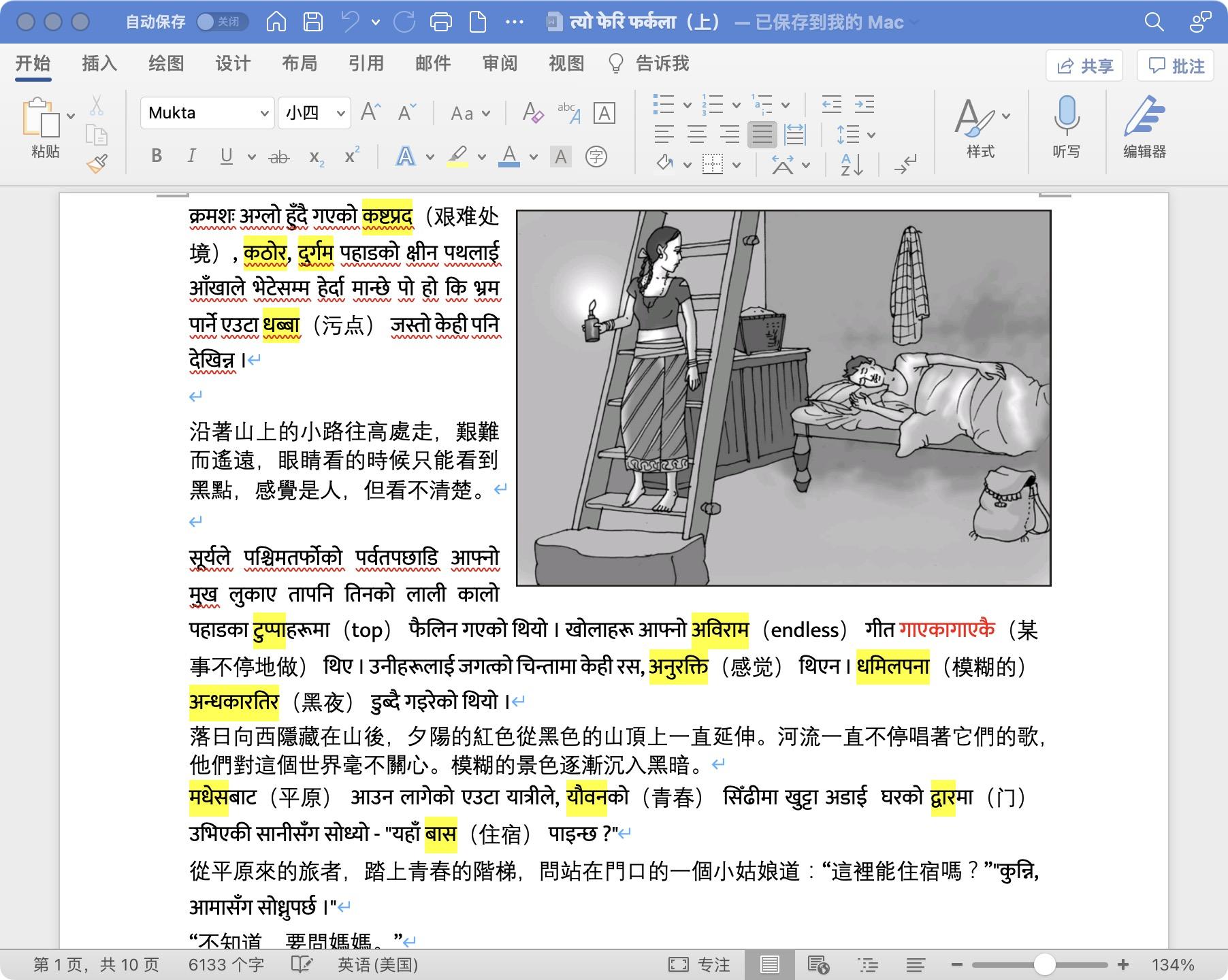

However, not everyone had an impression of Nepal before deciding to major in the Nepali language. Such is the case for Wang Zihao ‘Rajkumar’, a Nepali language master’s student at Tribhuvan University. Originally from Heilongjiang Province in China, Rajkumar had a strong inclination toward learning languages in general. While he knew he wanted to focus on learning a new language, which would allow him to skip the gaokao (高考), the Chinese college entrance examination, he was still torn between his choices of Russian, Malay, and Nepali. However, it was the institution that listed him for Nepali, and he accepted his fate. His Nepali teacher named him Rajkumar, as his Chinese name 王子豪 translates to ‘prince’. While attending TU for his master’s degree, he is also teaching Nepali to Chinese students online at Xizang Minzu University.

Chinese students like Rajkumar who choose to study Nepali in Nepal itself are normally briefed about the host country before they arrive.

“We were informed about Nepal’s development condition, which definitely helped me avoid having a strong negative impression when I first arrived in Nepal,” he said.

Furthermore, as aspects like Nepal’s poverty and its lack of development haven’t been sugarcoated by the Chinese media, this allows Chinese students to mentally prepare themselves for what lies ahead. Ambar, knew about the frequent power cuts and slow internet before coming to Nepal, allowing him to lower his expectations from the get-go, resulting in him feeling quite satisfied with his first visit to Nepal.

As the Chinese saying goes, ‘百闻不如一见’ (to see something once is better than to hear about it a hundred times), learning about Nepal’s history, culture, and unstable politics are better seen and experienced than read about. When Bijaya was in Nepal for his exchange program, he had the opportunity to experience the Dashain festivities as well as enjoy Tihar, which has now become his favorite Nepali festival.

“The Hindu tradition of cremation at Pashupathinath helped me observe the concept of life and death on a deeper level, which still continue to fascinate me,” said Bijaya.

How and why Nepali?

It was 2018, and we were manning the Nepali stall at Peking University’s International Cultural Festival when Bijaya came rushing up to us. He caught us by surprise with his fluent Nepali and his enthusiasm for Nepal. The next time we met him was at a Dashain celebration in the Nepali embassy in Beijing, where he performed a Nepali dance and sang ‘Yo Maan Ta Mero Nepali Ho” while clad in a daura surwal along with his fellow students majoring in the Nepali language.

But why are Chinese students like Bijaya so enthusiastic about Nepal, and why do they learn Nepali?

For many students, the reason is not an affinity for Nepal or the Nepali language, but rather, one of convenience. Selecting an undergraduate or Bachelor’s degree major in China is not the same as it is in Nepal. After Rajkumar completed high school, his interest in language drove him to pursue his studies in small languages, which also conveniently allowed him to avoid the gaokao, and directly join an undergraduate program in Nepali.

The gaokao, or National College Entrance Exam, remains integral for a majority of Chinese high school students, playing a decisive role in their futures. Students who pass their exams with flying colors usually get the opportunity to not only enroll in the best universities in China, but also decide on their major. Meanwhile, students who don’t do well have to settle for whatever university is ready to admit them, or they have to give the exams again.

We’ve known Chinese students who chose to major in smaller languages like Swahili, Mongolian, and even Burmese at Peking University simply to gain admission to a top university. For Ambar, it was his gaokao score that decided his major, and he believes that “the Nepali language chose him instead”. Jenisha also shares the same reason for selecting the Nepali language as her major. While the same scores may allow them to study their desired major in a smaller city, their decision to study small languages are usually driven by their desire to attach themselves to a higher-ranked university in a bigger city.

The learning process

A WeChat page operated by Chinese students majoring in Nepali at the Communications University of China is named Níyù (尼遇), meaning ‘an encounter with Nepali language’, but it is also a homonym for Níyǔ (尼语), meaning Nepali language. One of the videos has a few students teaching the differences between the ‘l’ sound and the ‘r’ sound, leading to jokes about how any confusion could result in them mixing potatoes (आलु) with peaches (आरु).

Through this platform, students demonstrate their observations about the Nepali language, sharing tips and tricks on learning Nepali, as well as documenting their learning process. A popular method of studying in China is memorization, which Jenisha shared as her study tip. She would memorize a set of Nepali vocabulary daily and keep practicing by herself or with her classmates. Bijaya, on the other hand, chose to learn the language through other means, like watching videos and listening to Nepali songs. His favorite song is the Nepali national anthem.

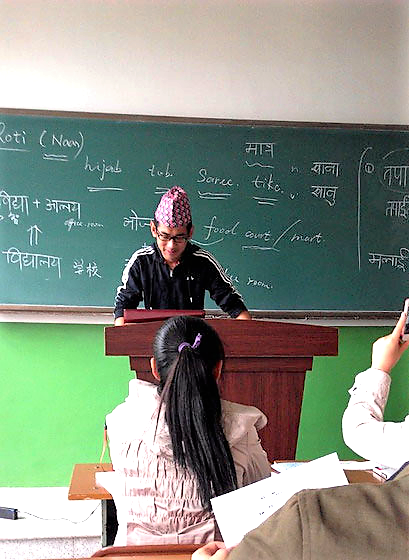

At university, students begin with the basics of the Nepali language, ranging from speaking, reading, and writing to listening in the initial semesters, and move towards written and verbal translations as well as Sino-Nepal and Nepal-India relations and history. While the majority of teachers are Chinese, there are still a handful of Nepali nationals who teach the language, providing students with an opportunity to learn from a native speaker and thus improve their language skills.

However, most of the effort to learn Nepali comes from the students themselves. Rajkumar admits that the environment isn’t conducive enough for Chinese people to learn Nepali, as there are very few Nepali nationals with whom they can interact with to improve their language skills.

“Knowledge exchange is an important aspect of people-to-people relations, and frequent interactions could be a perfect way to enhance it,” said Ambar.

The only time that Chinese students get to interact with Nepalis is during their semester exchange program, which is no longer an option due to the Covid-19 pandemic. Nepali language majors have not had an exchange in Kathmandu in two years. Ambar has been teaching the first batch of Nepali language majors from Beijing Foreign Language who are going to graduate next year. And although the students have learned the language and have gotten the chance to learn about different aspects of Nepal through Ambar’s experience, they have not been able to come to Nepal and experience the culture first-hand.

“It is tragic that these students will be graduating from university next year with a degree in Nepali language but without stepping foot in Nepal,” said Ambar.

Among this batch of students is Jenisha, who not only expressed disappointment at not being able to visit Nepal, but also complained about the lack of a suitable environment to practice Nepali in China. Moreover, there are very few Nepali teaching resources in Chinese, and the difficulty of many materials does not meet the current level that the students require.

Gathering from our own anxious experience of being some of the only international students in the class in Beijing, we asked Rajkumar if he felt similarly about being the only foreigner in his master’s program at Tribhuvan University. He confessed that he was mentally prepared “to be the worst in class” but he also shared that his Nepali classmates had been very supportive and were helpful during his learning process.

A win-win for both sides

The introduction of the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) has been a boon for Nepali language majors in Chinese universities. According to Rajkumar, knowing Nepali “creates less competition for jobs that require extensive knowledge of the Nepali language” and now with developing relations, increasing exchanges, and bilateral projects through the BRI, Chinese students are more motivated than ever to learn the Nepali language.

Bijaya too said that his parents were supportive of his decision to study Nepali as they were now more aware of the friendly relations between Nepal and China as well as the prospects of the BRI.

“Considering that Nepal is an important country along the BRI and a good friend of China, my parents were supportive of my decision to learn the Nepali language from the start, and they hope that I will be able to make great contributions to improving Sino-Nepal relations,” said Bijaya.

After graduating, a majority of Nepali language students either decide to work for Chinese state media like China Radio International’s (CRI) Nepali service, which Jenisha aspires to, or for government and party translations divisions like Bijaya does. Some, like Ambar and Rajkumar, go on to teach Nepali in various universities.

During the 2021 undergraduate graduation ceremony of China’s Communication University, valedictorian Liu Xiaoli, a Nepali language major, began her speech by acknowledging then Nepali ambassador to China, Leela Mani Poudel’s visit to her university four years ago. She credited him with reminding her of the importance of learning Nepali and her role as an ‘ambassador’ in Sino-Nepal relations. Many Chinese students who learn Nepali feel the same way, that they are assisting in building better understanding between two neighbors. Understanding each other's languages can be a stepping stone to deepening Sino-Nepal relations, which could prove to be more impactful on a people-to-people level.

Aneka R Rajbhandari Aneka R. Rajbhandari holds a degree in political science from Peking University and is pursuing her Master’s in Chinese Politics from the Silk Road School at Renmin University.

Suniva Chitrakar Suniva Chitrakar is an undergraduate student majoring in International Political Economy at Peking University.

Longreads

Features

74 min read

A resolution to the disputed territory along Nepal’s northern boundary will come only when India and China agree to demarcate their border

COVID19

5 min read

The coronavirus has cut through the democratic facade to show how deep inequality runs in Nepali society

Longreads

Perspectives

19 min read

Anti-secular voices demanding a return to Nepal’s character as a Hindu state are on the rise but they ignore the larger danger to Hinduism – Hindutva.

Explainers

3 min read

Co-passengers on the flights taken by the latest Covid19 positive patients pose probable risk to public health safety due to the absence of strict quarantine measures imposed by TIA

COVID19

News

3 min read

A daily summary of Covid19 related developments that matter

COVID19

News

3 min read

A daily summary of all Covid19 related developments that matter

Features

5 min read

The politics of the deaths of individual bodies, social groups, or entire populations has become increasingly normalised

Photo Essays

3 min read

Nirman Shrestha uses his art to document his experience of living with depression.