The Wire

Features

14 MIN READ

New research reveals high-level tensions in Kathmandu after the 1964 Khampa raid against the Chinese

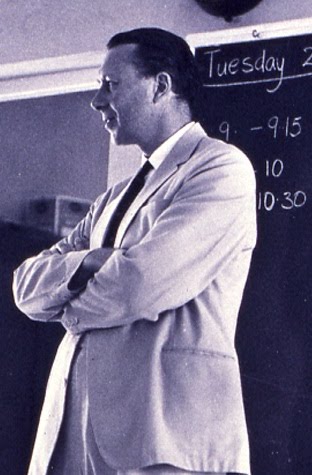

A recent study of two Foreign Office files in the UK National Archives [371/176118 and 371/176120] shed interesting light on events in Kathmandu in July 1964 which put Antony Duff, the recently arrived British ambassador, in a predicament, seriously discomfited the monarch, and caused major problems for Panchayat ministers and officials.

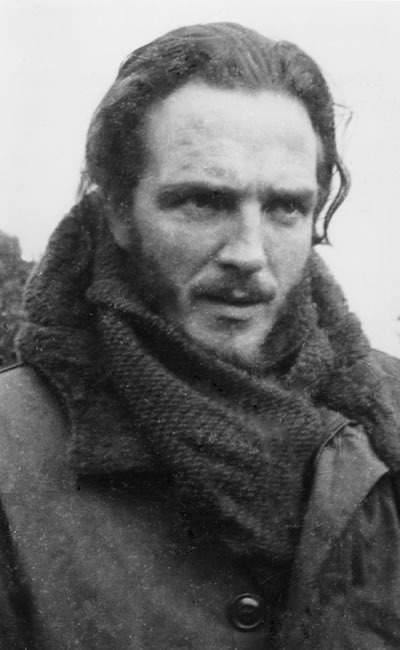

The man at the center of the events was a dedicated supporter of the Tibetan cause called George Patterson. He was a former missionary in Kham and spoke the Kham dialect fluently. He arrived in Kathmandu in March 1964 and was later joined by Adrian Cowell, a gifted documentary film maker, and Chris Menges, an experienced television cameraman. Their ambitious mission was to make contact with Khampa fighters in Mustang and film them carrying out a raid so that the world could see that Tibetans were still actively fighting the Chinese.

The buildup in late 1960 of Khampas in Mustang and their later dominance in the area was a badly kept secret. An article in The New York Times on March 3, 1962 quoted a Nepali foreign ministry spokesman as saying that unidentified aircraft had been dropping arms to about 4,000 Khampas in Mustang. The same article said that official Indian sources were expressing strong concern that the buildup of Tibetans on Nepal’s northern border could lead to China sending troops into Nepal. There were 2,000 Khampas in Mustang and the first two air drops to them, organized by the United States Central Intelligence Agency, had taken place in April 1961 and December 1961. In each case, two Hercules aircraft had delivered the weapons to a drop zone 10 kilometers inside Tibet, just across the border from Mustang. The weapons dropped were mainly of Second World War vintage.

The CIA’s intention from the outset was for the Khampas to establish positions along the roads within Tibet, but despite sustained pressure (which increased considerably after a third and final air drop into Mustang in May 1965) such a move never took place. Setting up bases in Tibet would have led to heavy casualties on the scale of those suffered by Khampas who parachuted into Tibet between 1957 and 1962 after the People’s Liberation Army had fully mobilized to meet the threat. Of the 49 men inserted, 37 were killed, most of them in pitched battles against the PLA. Lightly equipped guerrilla forces simply cannot stand and fight conventionally equipped armies supported by artillery and fighter ground attack aircraft.

The same heavy attrition occurred when the CIA shifted their point of effort in early 1964 to infiltrating small groups of Khampas into Tibet on intelligence missions. Four members of one of these groups were arrested in Kathmandu in June 1964 following a brawl. One of Duff’s dispatches gives the detail of this arrest as told to him by the Inspector General of Police, PS Lama. Lama told Duff that the Khampas were trained abroad and were on their way to the border. He also gave Duff a list of sophisticated surveillance and communication equipment taken from the Tibetans which, they said, had been given to them in Kathmandu by Hugh McDevitt who was employed as the manager of Air Ventures, which operated two helicopters for the United States Agency for International Development.

All of this indicates that from an early stage the Nepali authorities knew what was going on in Mustang and who was backing the Khampas there with money and material. There was therefore no chance that the Nepali authorities would allow Patterson anywhere near Mustang but they underestimated the man’s guile and determination.

In his book, A Fool at Forty, Patterson describes the web of deceit he spun in Kathmandu to cause maximum confusion about his real aim beneath the cover of making “a TV film about Nepal.” King Mahendra was traveling in the Far West, but Patterson saw most of the key people: Tulsi Giri, the Chairman of the Council of Ministers; Prakash Thakur, the Chief of Protocol; Mr. Banskota, the Director of Publicity; and General Padma Bahadur Khatri, the Foreign Secretary. He also had a two-hour meeting with Mahendra’s brother, Prince Basundhara.

Patterson clearly pulled the wool over all their eyes as he quickly got permission to start filming in and around Kathmandu. His application to go Mustang was refused but on a visit to a Tibetan camp near Trisuli, Patterson was informed about a small Khampa group in Tsum. After some delay he obtained a permit for “a trek to Pokhara.” He had a further slice of luck when three separately nominated liaison officers all found some excuse not to go. At the last minute, a young college student was nominated and accepted. Soon after getting the permit, the group headed to Arughat at which point they left the trail to Pokhara by turning north up the Buri Gandaki. After passing the police check post and Indian wireless station at Setibas (one of 17 established along the northern border by secret protocol in 1950 and withdrawn in 1969), they left the line of the river to head north east up the long, steep trail to Tsum.

Contact was quickly made with the small Khampa group of 15 men. They had been dispatched from their main base in Mustang two years earlier to establish an outpost in this distant location. They had one Bren Gun and eight rifles between them, and no means of communication. Tendar, their commander, had led reconnaissance sorties across the high snow passes that marked the border to monitor traffic on the Dzonkha-Kyrong road, but with supplies from Mustang having to come on a long and tortuous trail across the Thorung La and Laryka La passes, little offensive action had taken place.

At the time there was also apparently a lull in cross border raids from the main Khampa group in Mustang. A July 1964 dispatch from Duff reported a meeting he had with Michael Peissel who “recently had spent two months in Mustang getting material for a book.” Peissel gave him a detailed account of where the Khampa camps were located and told him that there had been no raiding across the border since early 1963 “after the Dalai Lama had sent word that the raiding was to stop and the Tibetans were to settle down peacefully where they were and cultivate the land.” CIA sources also report this lull but give different reasons for it.

Patterson lost no time in putting his proposition to Tendar. With no means of checking with his superiors in Mustang, Tendar had his doubts. To decide the issue, he went to the gompa to cast the dice. The result was a clear indication to carry out the raid. On June 7, 1964, Tendar, with his eight lightly armed men, the three foreigners, and three Khampa-provided porters, crossed the high snow passes that marked the border. Two days later at about two in the afternoon, having been in the ambush position since before dawn, they attacked four unescorted PLA vehicles traveling on the Dzonka-Kyrong road. Three vehicles were damaged and eight PLA soldiers killed. Patterson subsequently gave a detailed account of the raid to Charles Wylie, the defense attaché in the UK embassy, and listed all the weapons carried. All except one were of the type dropped by the CIA. The exception was “one British rifle marked LSA & Co Ltd, 1919, which the Khampas claimed had been officially supplied to Tibet.” (In 1947, acting on a request for military aid, Britain supplied a substantial amount of arms and ammunition to the Tibetan government.)

In his book, Patterson’s detailed description of the raid closely follows the account he gave to Wylie, including how they left the student minder behind under the pretext that they were going to film refugees. The ambush was successfully filmed and the team returned to Kathmandu on June 27, 1964. Various lurid accounts have appeared of what happened next, including stories about the team being pursued to the border by the police and the Khampas misinterpreting a CIA order to retrieve the footage as a directive to kill them. Duff’s dispatches are clear and generally tie in with what Patterson says.

On the morning after they returned, Cowell dispatched the footage of the raid on the first plane out which happened to be going to East Pakistan. A few days later, the three of them went to see Duff to confess all, mainly on the grounds, Patterson says, that they thought it was the proper thing to do. (Duff had entertained him to dinner prior to his departure but he had said nothing about his true intentions.) Cowell and Menges were dubious, but Patterson agreed that Duff could pass the information to Mahendra at an audience already fixed for the evening of Friday, July 3, 1964. Duff waited until the Friday morning to alert London to what had happened. One of his two telegrams that day stated that he was going to inform the US ambassador. It would be reasonable to assume that this is when the CIA would have been first alerted. At this stage the UK was still accepting categorical denials from the US that it was involved in supporting the Khampas. Subsequently the CIA blamed Baba Yeshi, the Mustang commander, for ordering the ambush to get publicity. He was reprimanded and the flow of funds to Mustang was stopped for six months. Tendar was recalled to Mustang and reassigned to administrative duties.

Mahendra’s first reaction was to tell Duff that the film would be “a big headache for us and for you.” In a later audience, Mahendra told him that the Khampas constituted one of his major problems though many considered that he was at best ambivalent on the subject. However, such apparent sympathy clearly counted for nothing given what Patterson was now about to expose to the world. Immediately after meeting Duff, Mahendra summoned the foreign minister, Kirti Nidhi Bista. He lost no time in transferring the monarch’s ire to his subordinates at a meeting he called on Saturday morning. Duff reported that “the main brunt fell on Padam Bahadur Khatri who took it especially hard because he would much sooner not have known anything about it all.”

That same morning, as previously planned, Cowell and Menges left Kathmandu to drive overland to India via Rauxal, accompanied by their student liaison officer. Patterson stayed on in Kathmandu because his wife, a surgeon, had arrived in his absence to help in the United Mission Hospital, bringing with her their three small children. Cowell and Menges were detained overnight at the border but left the next morning for Calcutta. Some innocuous film footage and audio tapes were confiscated. These were later returned to them; the tapes through the UK embassy in Kathmandu and the film from the Nepali embassy in London. Duff reported that the palace had given the order to release them without informing the foreign secretary. Two days later he thought they were still under arrest and being brought to Kathmandu to face disciplinary action

A week later Duff reported: “Judging by conversations with the King and the Foreign Minister at a reception, I have acquired no merit at all for telling the Nepalese about the sortie over the border into Tibet. The Foreign Minister indeed muttered something about it being sometimes better to conceal things for a while.”

At the same reception Mahendra said that the film ought to be stopped. Duff told him this was not possible. Patterson and Cowell had told Duff that they would wait for three months before showing the material. In the event, the finished film, called Raid into Tibet, was not shown on British television until May 9, 1966. It was widely acclaimed but, contrary to many reports, there is no record of it winning the Prix Italia. (Cowell did win it in 1971 for his documentary about a remote Amazonian tribe: The Tribe that Hides from Man.)

Patterson was clearly not prepared to sit on his story for 18 months. In March 1965 he wrote a lengthy propagandist-style article on the raid in The Reporter, an American biweekly news magazine published in New York. It described the ambush in graphic detail and made it clear that the action had been filmed for television. Large extracts immediately appeared in the Hindustan Times, under the heading: “Nepal-based Khampas harass Chinese.” The files show that the articles caused concern among British officials, which suggests that perhaps ATV, the independent company who finally transmitted it in the UK, had been persuaded to delay showing the film. An earlier note in the files indicates a determination to do this if pressure on Patterson failed.

Throughout the furor in Kathmandu over the filming of the raid, Duff had argued that some control over the film’s final content might be achieved by taking a conciliatory approach with Patterson. Only Mahendra and the palace were receptive: Padam Bahadur Khatri and his cohorts wanted some measure of retribution. This manifested itself at the airport two weeks later when, without producing any authority, the police prevented Patterson from leaving on his booked flight. When Duff complained, no one in Kathmandu could or would identify who had given the order. Three days later Patterson was allowed to leave having signed a five-line note saying essentially that he was sorry for any inconvenience caused by visiting Setibas, which was not listed on his permit, and that he had not visited Mustang.

“Why that curious little statement should have satisfied anyone is merely one of the many mysteries about Nepalese behaviour throughout this affair.” That comment from Duff’s final dispatch on the event seems an apt way to end this tale as it also neatly conveys the opaqueness of government during the Panchayat days, which so confused outsiders and so suited the monarch.

In addition to the UK archive material, and Patterson’s book, other information about Tendar and the Khampas in Mustang comes from the well-sourced book: The CIA’s Secret War in Tibet by Conboy and Morrison.

(An abridged version of this article first appeared in The Nepali Times on January 3, 2014.)

This was an important article for me. It was the first to be published in the newly launched online magazine, The Record, and was also the first article I wrote which drew heavily on contemporaneous evidence from British Foreign Office files in the National Archives. An example of the value of these is given by the corrections I have made to the endlessly repeated lurid accounts of what happened to Patterson, Cowell and Menges after they returned to Kathmandu. These include stories about the threesome being pursued to the Indian border by the police, and the Khampas misinterpreting a CIA order to retrieve the film footage as a directive to kill them. The dispatches from the British ambassador, based on first-hand knowledge of what was happening in Kathmandu, including conversations with the threesome, make clear that such accounts are totally wrong.

As mentioned in the article, there has also been much speculation on the reason for the apparently long delay in showing the footage shot in Tibet but, in a telephone conversation with Chris Menges after the publication of the article, he explained that whatever the Foreign Office files or others might say, there was no suppression. The reason for delay, he explained, was much more mundane. After Nepal and India, he and Cowell went directly to Hong Kong, Thailand and Burma to shoot footage for other documentaries. Only when they eventually returned to UK, could they finally edit the Tibet film along with the other material. Raid into Tibet was shown as a two-part series, under the name of Rebel. The second part was, The Unknown War, based on a seven-month stay with the fighters of the Shan state challenging the authority of the Burmese military rulers. Also produced from the Burmese visit and stays in Hong Kong and Thailand was, The Opium Wars. These documentaries were all shown in UK on ATV in 1966, along with three other Adrian Cowell documentaries on Buddhism in Tibet, Thailand and Japan.

Added to the original when it was published as a chapter in the author’s book, “Essays on Nepal Past and Present”, in September 2018.

Cover photo: Ruins of an old military camp where the first Tibetan refugees in Nepal trained and attacked the Chinese in the mountains of Tibet. Tserok, Mustang, Nepal. Erik Törner/Flickr. Republished under CC license BY-NC-SA 2.0.

:::::

Correction: May 6, 2014

A previous version of this article conjectured that Chris Menges did not film the footage of King Mahendra that appeared in Raid into Tibet. Chris Menges did in fact film the footage

Sam Cowan Sam Cowan is a retired British general who knows Nepal well through his British Gurkha connections and extensive trekking in the country over many years.

Opinions

6 min read

Angira’s death is one more example of brutality against Dalit bodies

Explainers

Perspectives

5 min read

Public quarantine facilities are becoming time-bombs; it’s time to rely on home quarantine

Features

5 min read

The project has become a geopolitical ping pong

Week in Politics

6 min read

The week in politics: what happened, what does it mean, why does it matter?

Features

8 min read

Today is Veteran’s Day in the US, but Nepali contractors who work for the US war effort remain under-appreciated and underpaid.

Features

5 min read

Inside Qatar’s deportation centre, migrants detained under woefully harsh conditions

COVID19

News

3 min read

A daily summary of Covid19-related developments that matter

COVID19

News

3 min read

A daily summary of Covid19-related developments that matter