Photo Essays

4 MIN READ

New photo collection brings light to women's participation in political struggles

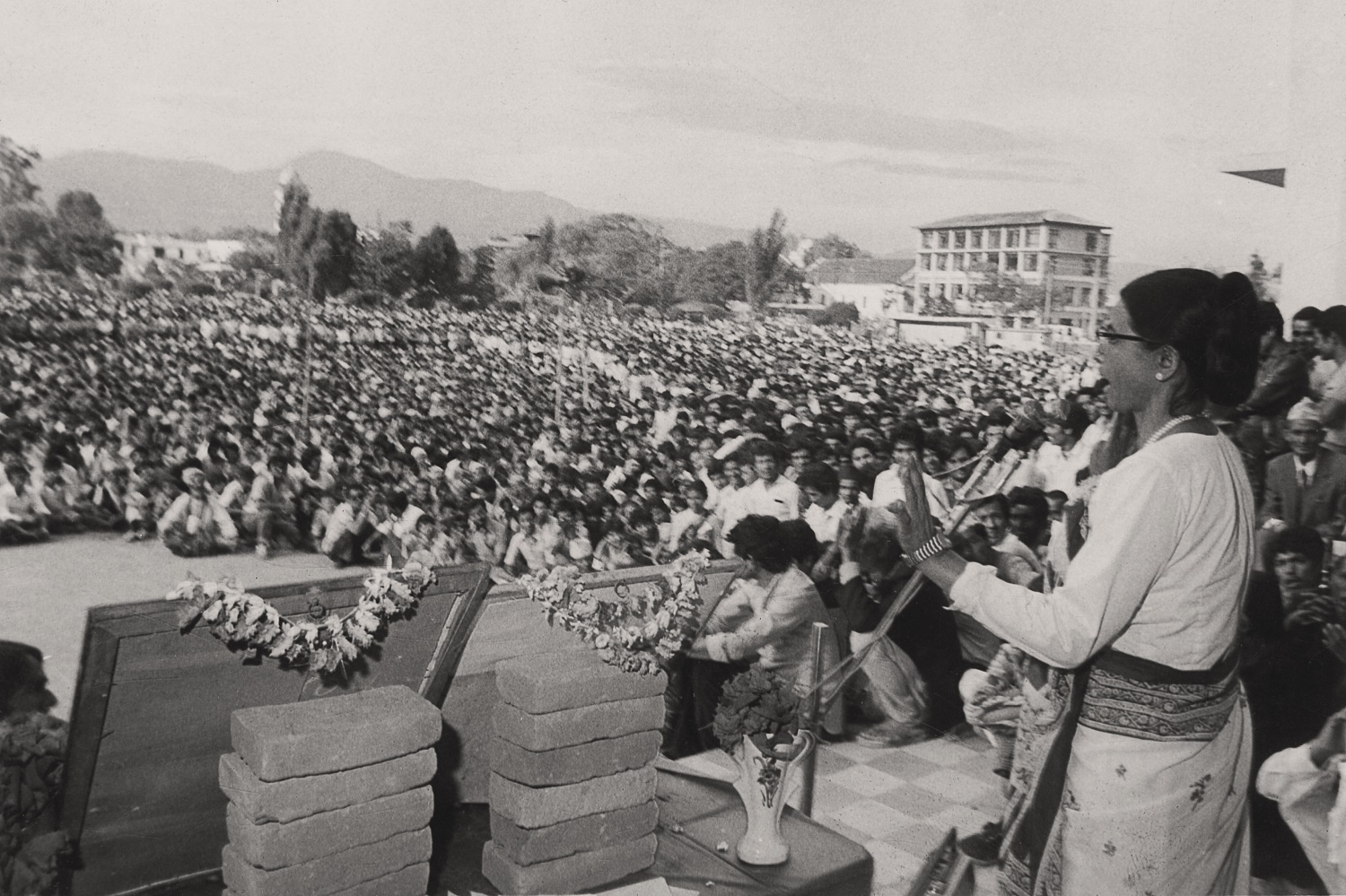

To become public is to be seen and accounted for in history. The journey of Nepali women from within the boundaries of domesticity to the openness of public life is a move from obscurity to memory. A history of women is first and foremost a social history.

The history of Nepal’s struggle for democracy and progress over the last century is dominated by men and treats women as auxiliary. Women themselves, however, were guided by this new era’s promise of inclusion in a universal community. Looking into this history from women’s perspective brings attention to the ways women made new positions and new subjectivity possible through their entry into popular politics and public life—and also the ways these possibilities made the contours of male-dominated history susceptible to new meanings.

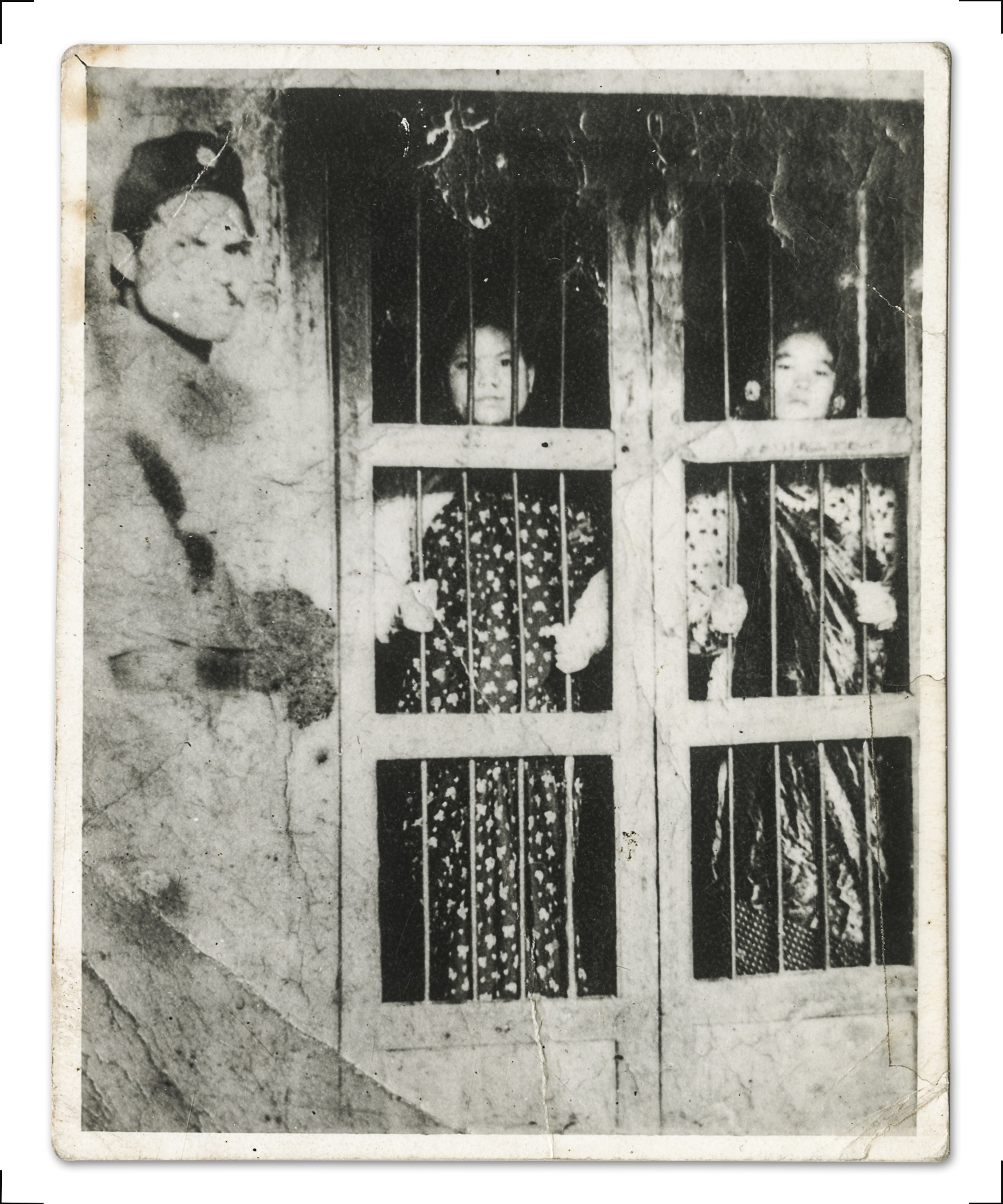

Social worker Punyaprabha Devi Dhungana founded All Nepal Women’s Association in 1951, through which she launched several campaigns to raise awareness about women’s oppression. Also seen is the facade of her organization’s office building in Thamel, donated by Kaiser Shumsher Jang Bahadur Rana. She used to walk to the office from her home in Chabahil and drop in door to door on the way canvassing support for the cause. Badri Binod Dhungana Collection/Nepal Picture Library

Starting with the movement against the Rana oligarchy, we move through the decades seeking to transmit the memory and amplify the visibility of women in Nepal’s political history. The images and the narratives of the past needed to be freed from the grips of economically and culturally dominant groups and presented to disclose—in the true spirit of inclusion and democracy—the diversities, differences, and dissensions of Nepali history.

These images are part of Feminist Memory Project, currently under exhibition as part of Photo Kathmandu, is curated by Diwas Raja Kc & NayanTara Gurung Kakshapati. For more information about the exhibition, and Photo Kathmandu 2018, please visit the festival website.

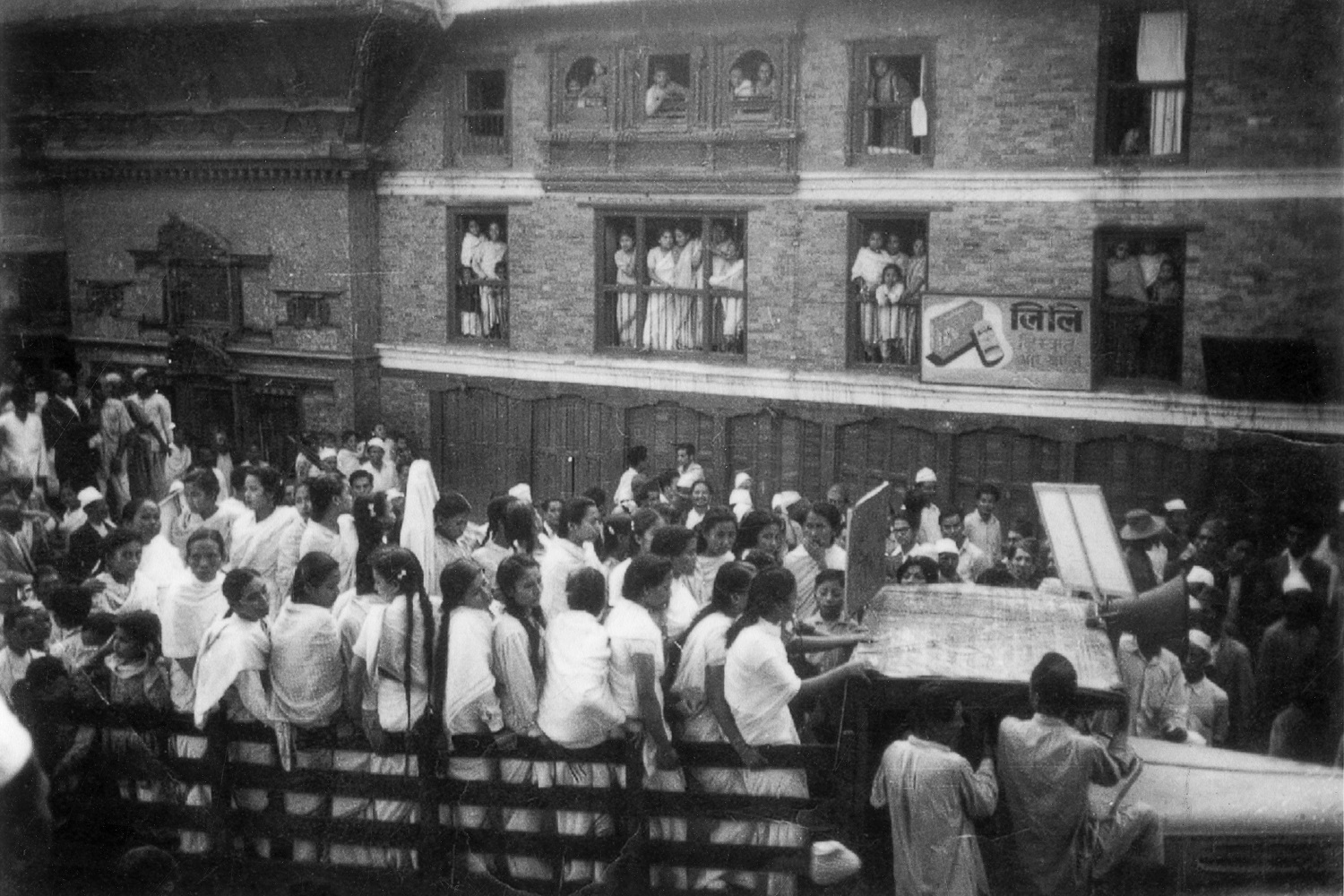

[Feature image: Kathmandu | 1981, Women from all walks of life gather for a mass meeting in Kathmandu to submit a letter of protest to the government following the rape and murder of sisters Namita and Sunita Bhandari in Pokhara that rocked the country. Hisila Yami Collection/ Nepal Picture Library]

:::

We welcome your comments. Please write to us at letters@recordnepal.com.

Nepal Picture Library Nepal Picture Library is a digital photo archive run by photo.circle that strives to create a broad and inclusive visual archive of Nepali social and cultural history, and has collected over 70,000 photos from various sources across Nepal.

Interviews

Longreads

Features

44 min read

As the crisis unfolds in Myanmar, two Burmese youths talk about their experiences and what life is currently like on the ground there.

Perspectives

Longreads

20 min read

Violence undocumented is violence denied, and new writing from Kalimpong and Darjeeling — which includes Chuden Kabimo’s Song of the Soil — is correcting this historical wrong.

Podcast

History Series

1 min read

The Rana regime ends and King Tribhuvan promises a Constituent Assembly

COVID19

News

5 min read

A daily summary of Covid19 related developments that matter

Recommended

Perspectives

7 min read

Rupa Sunar’s act of resistance not only sparked the predictable rage of Bahuns and Chhetris but also unmasked many Janajatis who see themselves as crusaders of justice for the marginalized.

COVID19

News

3 min read

The dispersed movement of people and animals roaming freely have made wildlife more vulnerable to poachers

Features

Longreads

Popular

33 min read

One of the key questions regarding the historical development of the Nepali state pertains to its independence

Features

10 min read

The Abbot of Tengboche Monastery, Ngawang Tenzin Zangbu, who passed away on Oct 10, was renowned for his commitment to the sacred valley of Khumbu and the Sherpa people