Perspectives

4 MIN READ

Has gender equality actually been achieved or does it only represent a partial shifting of powers from male Khas Arya individuals to women from the same clan?

In the past decade, an issue that has found central space in political discourse and yet remains contested in Nepal is the debate around inclusion. The inclusion agenda is aimed at the structural transformation of a public sphere long monopolized by elite males from the Khas Arya community. The idea of inclusion remained pivotal in ending the structural marginalization of women, Dalits, Janajatis, Madhesis, LGBTQIA, people with disabilities, and other marginalized communities.

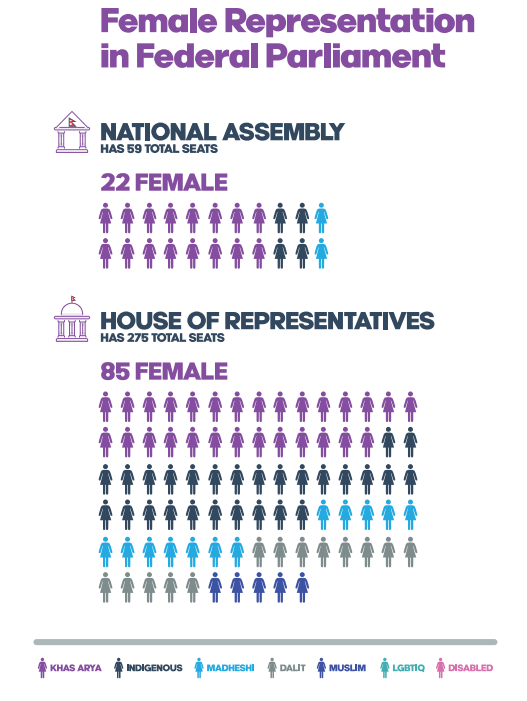

The one achievement of the democratic republic of Nepal that has been lauded ever since the dawn of republicanism has been the inclusion of women in the first Constituent Assembly, followed by the outstanding representation of women in local governments. Women’s representation has not only become a symbolic illustration of greater democracy in Nepal but the numbers have also been crucial in portraying the country as a champion of gender equality.

But pursuing inclusion means disentangling the complex relations between equality and difference, which generates power and subordination. Inclusion as a normative ideal of democracy requires equal redistribution, recognition, and participation. However, when one applies an intersectional lens, the larger question that arises is, has gender equality actually been achieved, or does it only represent a partial shifting of powers from male Khas Arya individuals to women from the same clan? And what does such a skewed transfer mean for the larger arena of building a gender-inclusive public sphere?

A recent study by VOW Media illustrates how the public sphere remains an expression of a singular ethnic character, with intersectionality at the margins. The study shows how deceptive representation and the inclusion of women have been. Women with intersectional identities still have a minimal presence in all spheres of public and private institutions with Madhesi and Dalit women almost non-existent in most leadership positions.

For example, the findings show that among editors of the mainstream media, there are just two Madhesi women and one Dalit woman editor while the rest are Khas Arya women. There are no Madhesi, Muslim, or Dalit women as chief district officers. Muslim women, LGBTQIA individuals, and people with disabilities are completely absent in leadership positions in institutions like the judiciary and the security agencies. The most inclusive institutions, as per the findings of the study, are NGOs and even in these institutions, Khas Arya women disproportionately outnumber women with intersectional identities.

The contemporary public sphere thus is skewed by power hierarchies, which the VOW study makes more than apparent. The over-representation of Khas Arya women in all structures is an appalling example of (un)inclusion being practiced in the name of inclusion. These structures ensure greater patriarchal authority and leave the traditional challenges of accommodating equality and difference in the democratic arena unaddressed. This state of inclusion is the result of placing women into the singular racist-ethnic-masculinist discourse on politics and the public sphere.

What has largely gone unnoticed is that this process is the tendency to reinforce attitudes, institutions, and structures that position some women as subordinate to other women. Such (un)inclusion has been made to look ‘natural’ but it is not. This ethnic bias, combined with patriarchy, posits that inequalities result from “inferior or different genetic endowment” and are therefore natural and inevitable. When gender is combined with ethnicity and race, it becomes another way to enforce social hierarchies that are established to be experienced as natural and normal.

There are different expressions at different times, but ethnicity, race, caste, and gender have historically determined the places that these people, especially women with intersectional identities, would occupy in the constitution of society’s political and economic organization. Therefore, intersectional positionality, as aptly captured by the VOW study, is critical to determining access to power and position. The social expression of the competition for access to power and privilege is always expressed through intersectional deprivations based on caste, ethnicity, race, and gender.

The current paradigm of Nepali un(inclusion) is best explained by Catharine MacKinnon in her seminal work A Feminist Theory of the State where she argues that “state power emerged as male power” and male power in its cardinal expression was ‘white’. This expression is further extrapolated by Gerald Torres and Katie Pace as, “Thus, as race is gendered, the superior race assumes the characteristics of the superior gender”. Hence what needs to be understood from these expressions is that racist supremacy expressed in any form is as much an expression of patriarchy. In Nepal, the excessive occupation of all public spaces by women from one ethnic community exemplifies the entrenched patriarchy and the expression of ethnic supremacy in a gendered form.

Therefore, in the given scenario, the creation of an intersectional public sphere remains a far cry in Nepal. The existing public sphere is still the manifestation of the older suppositions of patriarchal politics and an expression of an uneasy relationship that women with intersectional identities share with the public sphere. Destroying hierarchies based on caste, race, class, gender, and ethnicity is only possible by reshaping the structures that comprise the public sphere. Therefore, the struggles for racial, ethnic, and gender equality to change the inherently exclusionary public sphere remain a long and arduous journey. Reshaping gender, ethnic, and racial formations within all democratic institutions in a more politically inclusive way is only the first step.

Kalpana Jha Kalpana Jha is a PhD candidate at the University of Delhi and author of the book, 'The Madhesi Upsurge and the Contested Idea of Nepal'.

Perspectives

8 min read

The Prime Minister’s habit of bulldozing decisions through party and government has alienated all his allies

COVID19

Explainers

4 min read

The unreliable RDT kits deployed by the govt have made the Covid crisis worse

Features

5 min read

Unless Nepali migrant workers are allowed to vote from abroad, we won’t have a truly representative democracy

COVID19

News

2 min read

A daily summary of all Covid19 related developments that matter

Explainers

4 min read

The govt has callously suspended its campaign to repatriate stranded migrant workers

COVID19

Features

4 min read

The death of an inmate from Kathmandu’s Central Jail and the subsequent row over his putrefying body is a testament to the jail management's shortcomings in handling the coronavirus crisis

Week in Politics

5 min read

The week in politics: what happened, what does it mean, why does it matter?

Perspectives

7 min read

Bringing attention to the everyday abuse faced by women