Explainers

4 MIN READ

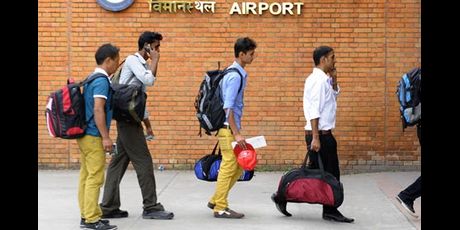

The nation is unprepared for the mass return of migrant workers from destinations across the world

Even as Covid19 cases have continued to increase in Qatar, Kumar Chaudhary’s life has been going on as usual. A Nepali migrant working in Gharafa, a suburb in Doha, Chaudhary works six hours every day, except on weekends. He spends his free time listening to music and catching up with family and friends on social media.

“Ours is plumbing and electrical work. We get to work indoors, even though we are prohibited from going to public places,” says Chaudhary, who is originally from Dang.

Not all are as fortunate as him. Since Qatar tightened restrictions on movement in public places from 9 March onwards in order to contain Covid19, thousands of Nepali workers have been rendered jobless, some without food or money, while more are likely to suffer a similar fate in the coming days.

Nearly 21,500 people, including an unknown number of Nepali workers, have tested positive for Covid19 in Qatar since the country confirmed its first case in late February. This led to the shutdown of hundreds of companies and resulted in mass layoffs, pushing already vulnerable workers to the brink. Qatar is home to around 400,000 Nepali workers, who are mainly employed as unskilled construction labourers.

“There is no work, no money. I just want to get out of this country as soon as possible,” Rudra, a Nepali worker stuck in the Sanaya area with a dozen of his friends, told The Record over the phone.

Rudra is just one amongst a host of Nepali workers scattered across the Gulf and beyond waiting desperately for international flights to resume so they can return home. Stakeholders, however, fear that this could just be the beginning of a reverse migration apocalypse.

“We are about to see what was always in the back of our minds--the mass return of workers from work destinations across the world. The shock will be felt in our economy and nearly every household for a long time to come,” says Ganesh Gurung, a member of the governmental think tank Policy Research Academy.

Nobody seems to know how many workers will return from abroad, although everyone agrees Nepal is just about to see one of its biggest reverse migrations in history. The irony is that the government doesn't even have updated figures of the number of Nepalis currently working abroad. More than six million people have acquired work approval from the Department of Foreign Employment since 1994. Some estimates suggest that there could be around three million people working abroad, besides those working as seasonal migrants in India, who do not require work permits. Most are concentrated in Malaysia and the Gulf countries, including Saudi Arabia, Qatar, United Arab Emirates, Kuwait, Bahrain, and Oman.

“About one million people will return immediately after international flights resume. There are many who are planning to buy their own tickets home,” says Pushkar Acharya, a trade unionist.

Most countries in the Gulf, which long thrived on oil and cheap labour, are facing a deep crisis due to the sudden fall of oil prices and the redirection of vast resources towards immediate medical care for millions of people, including migrants.

Countries like Saudi Arabia and Kuwait, where hundreds of industries have shut down, have already proposed to immediately return more than 70,000 Nepali workers, according to media reports. This number is likely to go up as more companies enforce mass layoffs or as workers themselves quit due to nonpayment or delayed payment of salaries.

In a statement issued on 20 April, Amnesty International (AI) said that the abuse of migrant workers had become impossible to ignore in the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) countries since the outbreak of Covid19.

The GCC, a bloc of six countries comprising Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, Bahrain, Kuwait, Oman, and Qatar, is home to millions of expatriate workers, including an estimated 1.5 million Nepali migrants. Despite being some of the richest countries in the world, these countries could become problem spots for thousands of workers, especially undocumented ones, who face starvation.

“Sadly, they have also become notorious for the systematic abuse and exploitation of the migrant workers who contribute so much to their economies. Unpaid wages, forced labour, dangerous working conditions and unsanitary accommodation facilities are too often part and parcel of the migration experience,” AI said in a statement.

Experts say the Nepal government will face significant challenges in providing jobs to hundreds of thousands of possible returnees along with the 500,000 prospective workers entering the job market each year. Some even fear that it could create a perfect recipe for those trying to steer the country towards another round of war.

“The situation could turn volatile, as hunger can be more dangerous than disease. We all need to be careful,” says Acharya.

Since mid-March, all work destinations, except South Korea, have suspended the hiring of workers from Nepal. The sudden suspension has prevented the outflow of around 10,000 workers each day, besides stranding around 40,000 workers who were in the final process of leaving for various work destinations.

“These were people who were ready with a visa and ticket in hand,” says Bishnu Gaire, president of Nepal's Association of Foreign Employment Agencies, the umbrella organisation of overseas job recruitment agencies. He says that around 1,100 Nepali workers had been leaving the country daily for foreign employment before the Covid19 lockdown.

The Oli government has done very little and looks ill-prepared to repatriate and quarantine stranded workers, let alone give them alternative livelihood opportunities. On 4 May, Foreign Minister Pradeep Gyawali said that the government was in no position to immediately evacuate workers from India or other work destinations. He also said that fewer workers than the numbers reported in the media were willing to return.

Government officials claim that the returnees can be employed through various employment schemes such as the Prime Minister’s Employment Scheme, although many experts say that these will be insufficient and ineffective in absorbing the close to 300,000 youth who leave for countries other than India in search for jobs each year.

Experts say that it is still not too late to correct past mistakes and promote the internal job market.

“Everybody knew this would happen someday. Nobody thought that day would come so soon. We have hardly any plans to accommodate those workers. We need to tread carefully,” says Gurung.

:::::::::

The Record We are an independent digital publication based in Kathmandu, Nepal. Our stories examine politics, the economy, society, and culture. We look into events both current and past, offering depth, analysis, and perspective. Explore our features, explainers, long reads, multimedia stories, and podcasts. There’s something here for everyone.

Features

4 min read

Hospitals that don’t abide by the MoHP’s directive won’t be able to continue operating

COVID19

News

3 min read

A daily summary of Covid19 related developments that matter

Perspectives

7 min read

Persons with disabilities face multiple hindrances to access basic reproductive health services and information. This leads to an adverse impact on their overall health and well-being and their participation in society.

Features

5 min read

The mass-quarantine centres in Nepal are only adding to the suffering of migrant workers returning from India

COVID19

News

3 min read

A daily summary of Covid19 related developments that matter

Features

9 min read

Nepali women are increasingly turning to podcasts to carve out a space to look at socio-political issues through an intersectional feminist lens.

Photo Essays

Features

16 min read

Retired British General Sam Cowan recounts the times he spent with five Gurkha Victoria Cross holders from the Second World War.

Perspectives

Opinions

5 min read

Why it will be a missed opportunity for Nepal if Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi cancels his visit to Janakpur