Longreads

71 MIN READ

An account of how and why, on Lipu Lekh in 1816, an East India Company surveyor interacted over three days with the Deba of Taklakot, the official representative of imperial China in the area.

![Trade and transhumance routes of the Bhotiya groups who inhabit the four high valleys of Johar, Darma, Chaudans, and Byans. [Image adapted and modified from Pahar Mountains of Central Asia Digital Dataset, 2006, Sherring (1906), Ryavec Karl E (2015), Web (1819).]](https://assets.rumsan.net/clients/recordnepal/QmVbpjMe5tmEQDJL1xPkLLv4w76tpXtnn3G64uHtT85sEp)

This article has its origin in these lines, concerning Surveyor Captain William Spencer Webb from my article, ‘The Gorkha War and its aftermath:’

During his survey work in Kumaon in the spring of 1816, Webb requested a meeting with the Chinese Governor of Taklakot. The meeting took place on Lipu Lekh on 28 May, 1816. In Webb’s words: “the Chieftain remained with me near five hours; sending for his pipe and large teapot, as seeming to consider me but an indifferent preparer of that beverage.” Webb’s report on his work in 1816 was read before a meeting of the Asiatic Society, with Lord Moira in the chair. [Vol 3, RH Phillimore's Historical Records of the Survey of India, pp. 45 and 46.”] His report of his meeting with the Chinese Governor on Lipu Lekh was thought to be important enough to be considered by the Board of the East India Company. [Lamb, British India and Tibet 1766-1910, Footnote 59, p. 40].

This ‘meeting’ had long intrigued me. In the highly stratified society of England in 1816, how could a mere surveyor feel confident enough to deviate from his primary task of fixing the northern and eastern boundaries of the newly annexed province of Kumaon to seek a meeting with the official representative of China, a great power that the East India Company was always peculiarly cautious about upsetting? Was this done solely of his own initiative? What was the real purpose of the meeting? What was discussed? Why would a senior Chinese official be interested in meeting Webb the surveyor?

In short, I was suspicious that there was a lot more to this meeting than first met the eye. Phillimore gives some additional detail but nothing that comes close to answering any of these questions.

A recent reread of Lamb’s book, referred to above, led me to what I was looking for. Footnote 59, states, “Board’s Collections, Vol. 552, Collection No. 13,384.” Ordering the reference up to read in the British Library’s Asian and African Studies Reading Room using the link given by Lamb did not work in this digital age but after a slight delay, I spotted it under IOR/F/4/552/13384. All that was needed was a trip to London to investigate. I collected Vol 552 from the desk and found Collection No. 13384 among five other files.

Transcribing the handwriting was not straightforward given my unfamiliarity with how the letters of the alphabet were written in manuscript at the time, to say nothing about the inconsistency of spelling. However, a quick scan through the pages told me that the file would exceed my hopes, starting with the information that there was not just one meeting, but three, spread over consecutive days. The discussions were wide-ranging but the main subject at each meeting was trade. Significantly, it is also clear from the papers in the file that bringing Webb and the Deba together was carefully prepared and that Webb had at the very least the tacit agreement of senior people in the East India Company [EIC] for him to try to contact the Deba of Ticklakot (modern spelling: Taklakot). There were other strong vested interests that saw a meeting between these two men as being of the utmost importance and were more than happy to facilitate it. In sum, I quickly appreciated that this was a file that was well worth investing time in.

Most of the file consists of an extended extract from Webb’s diary covering the three meetings but there are also some important and revealing letters from Webb to his superiors in the EIC and their response to his activities. Before analyzing the details in the file, here is some background on the main characters who feature.

Lord Moira, John Adam, and Edward Gardner

Lord Moira was the Governor-General and Commander-in-Chief, John Adam occupied the powerful position of Chief Secretary to the Government of India, and the Honourable Edward Gardner was the Commissioner for the affairs of Kumaon and Agent of the Governor-General in the province.

Gardner was a close friend of John Adam and whatever Adam knew the Governor-General would also know. It was a very tight circle. They had worked closely together to bring the Gorkha War to a successful conclusion but at a cost that had far exceeded all estimates. The East India Company was a commercial organization and its top priority was to pay a dividend to its investors. This meant that at the conclusion of the war, Moira and his two chief subordinates were under great pressure to deliver quickly on promised new sources of revenue.

In ‘The Gorkha War and its aftermath’, I gave this extract from Moira’s private journal. It conveys his thoughts, on the morning of 8 December 1814, not long before the invasion of Kumaon, on seeing the sunrise over the snow peaks of the Himalaya during an inspection tour of troops in the northern provinces:

“…..this immense barrier would seem sufficient to limit the concerns of India; yet at this moment I am speculating on the trade which may be carried on beyond it, should the present war with the Gorkhas leave us in possession of Kemaoon [sic]. From that province there are valleys between the hills which afford passage of not much difficulty, and greatly frequented, into Tartary. The holding of Kemaoon would give to us exclusive purchase of the shawl wool, to be paid for in cutlery, broadcloth and grain”.

During the war, Moira turned these aspirations into firm promises in letters to the Directors of the EIC in London, as in this example: “The province of Kamaon [sic] is intrinsically a valuable possession, from its revenue, its mines, and its timber. The command which it is almost certain to give of the exclusive shawl-wool trade may be regarded with much satisfaction. The ready communication which it furnishes with Tartary, offers a market for British manufacturers to an undefinable extent.” [Letter of 20 July 1815, [“Nepaul War Papers”, pp. 550 and 551]

With the war over, it was time to deliver on these promises, but Moira and his team had little knowledge of trading activities on Kumaon’s northern border during the 24 years of Gorkha occupation, or before, as hinted at in this letter from Moira to the Directors in London of 11 May 1815:

“Even this, perhaps, is little, when put in the balance against a benefit which we now only know to be great, without being able to measure its magnitude. The gap through the vast Himmaleh mountains at the northern point of Kamaon afford, as we have ascertained, not only a practicable, but a commodious road into Tartary. What extent of trade may be carried on through this passage may now be a matter of loose speculation; probably it will be very considerable.” [“Nepaul War Papers”, pp. 550 and 551] [My highlighting]

So, despite all the dreams and promises, Lord Moira and his team knew very little about the state of trade over the EIC’s new northern frontier but, fortunately for them, the promise of help was close at hand.

Captain William Spencer Webb

The main character in this tale is the surveyor, Captain William Webb, a man in whom the spirit of adventure burned very strongly. As a lieutenant in 1808, he accompanied F.V. Raper and Hyder Hearsay on an expedition to discover the sources of the Ganges. In his later work in Kumaon, to fix the northern and eastern boundaries of the newly annexed province, he wrote, “The whole survey having hitherto devolved upon myself, and, being ill-qualified as a draughtsman, my attention has been principally directed to the formation of the outline and comparatively little to the map, in which I have been in continued expectation to be aided by an assistant” [pp. 45, Vol. 2 Phillimore]. Phillimore writes that Webb’s main interest lay in fixing the snow range and exploring the Tibetan borderlands. As it turned out, this suited everyone’s interests.

The clue to the timing of Webb’s arrival in Kumaon, and the reasons why the Sugauli Treaty has no map attached to it, lie in a letter dated 3 May 1815, from John Adam to Edward Gardner. This short extract tells only part of the story:

“The terms of the convention concluded with Bum Sah and the other Goorka chiefs by which they engage to evacuate Kamaon and all the fortified places as a condition of been allowed to retire unmolested across the Sarda are highly approved by the Governor-General…

As soon as the Goorka troops shall have withdrawn from Kamaon and the passage of the Sarda be secured, your attention will be directed to the introduction and establishment of the authority of the Government throughout the province. On this subject, no instructions are deemed to be necessary, beyond which you have already been furnished; except in as much as refers to the boundary which should be assigned to the province. All the Maps in possession of this government are so incorrect, that no satisfactory judgement can be framed from them with regard to what the interests of the Company may require in that respect. [My emphasis] To the eastward, the Sarda appears to present a natural limit. Still the important object of securing the trade with Tartary through the Himmaleh mountains against the interference of the Goorkhas might not be attained by fixing that river as the boundary; you are therefore requested to satisfy yourself on this point”. [“Nepaul War Papers”, p. 571]

This letter from Adam was clearly prompted by the need of the EIC to ensure that its projected trade with Tibet over Lipu Lekh would be free of interference from the Gorkhas. His problem is that all the maps in possession of the government are so incorrect that he cannot give clear orders to Gardner on what boundary would achieve this. As the rest of the quoted letter makes clear, Gardner is given the authority, if necessary, to move the boundary with Nepal as far east as necessary to achieve what was required, and to adjust the Treaty terms accordingly. As the papers in the file make clear, Webb arrived in Kumaon as part of this project.

The Deba of Ticklakot

From Webb’s diary, we learn a lot about the character of “the Deba or Chief of Ticklakot a Chinese officer subordinate to the Viceroy of Gurdone”. The two men clearly developed considerable mutual respect and the Deba was very forthcoming with information about trading arrangements in his area and how Tibet’s complicated local administrative system worked at the time. The diary extract reveals that he was in the fourth year of his appointment as Deba of Ticklakot. Deba is a Tibetan term that denotes officials of varying rank in different parts of the Tibetan world; for example, the Kings of Mustang were sometimes referred to as deba, but the term also denoted local chiefs, rather like mukhiyas in Nepal, who were entrusted with collecting taxes.

As for the Deba’s nationality, I have taken advice and, based on numerous details in the diary, related to language, hairstyle, and place of birth, highlighted below, it is clear that the Deba was not Chinese, or even a Manchu, but a Tibetan from a central Tibetan aristocratic family, as was the case with numerous senior officials in Tibet under the Qing. They usually dressed in Chinese silk brocade, and in appearance and manners would have been quite unlike any of the ordinary Tibetans that Europeans would have encountered. At the time, British sources referred incorrectly to ‘the Chinese’ because, since they had an idea that they were dealing with the Chinese Empire, their interlocutors ought to be Chinese.

As the title of the file indicates, the Deba was answerable to the Viceroy of Gurdone. Gurdone is almost certainly a reference to Gartok, which was by far the biggest trading mart in that part of Tibet. ‘Gurdone’ could be a mixture of Gartok and Gargunsa which was the winter residence. It was also the residence of the two topmost representatives of the Lhasa government in the area who came from aristocratic families of Central Tibet and usually served for three years or so. In early British accounts, they are invariably referred to as “Viceroys”. Hence George Traill, Commissioner of Kumaon, writing in the 1820s, notes that, “a periodical fair takes place annually in September, at Gartokh, the residence of the Lhassan viceroy, which is principally attended by traders from Hindustan, Ladakh, Cashmer, Tartary, Yarkhand, Lhassa, and Liling, or China proper: under the first description are included, the Bhoteas of this province, though at present those of the Juwár ghât, alone enjoy the unrestricted privilege of visiting Gartokh.”

The details in Webb’s diary indicate that the Deba of Ticklakot at the time had a very firm grip on events in his area. He comes across as an impressive man.

The zamindars

It was not just senior officials of the EIC who had a keen interest in the future of trade from Kumaon into Tibet after the last vestige of Gorkhali government influence had been rooted out from the province. Just as interested were the people who lived in the border areas south of the Himalaya who depended on cross-border trade for their existence. The British referred to these trans-Himalayan traders as “Bhotiyas”, a term that was later applied to a great variety of groups. In Kumaon, and featured in this story, there are four such Bhotiya groups who live in the four high valleys of Johar, Darma, Chaudans, and Byans, as can be seen clearly in the map above. Each group speaks its own distinctive language, and the last three named collectively identify themselves as “Rang.”

Historically, zamindars were often hereditary owners of multiple villages and as such, were expected to collect taxes from local farmers and pass it on to the ruler to whom they were subject. In 1793, the EIC, under Lord Cornwallis, introduced what was known as the Permanent Settlement System in which zamindars became the proprietors of their land in return for a fixed annual rent. This ensured that they had a clear interest in the well-being and prosperity of those who worked on their land.

Webb’s guide on this frontier-fixing trip was the chief zamindar of Johar but he was accompanied by zamindars from other pergunaahs. All these men would have had previous meetings with the Deba of Ticklakot to discuss details of the annual trading trips of their people and the charges to be paid into the Deba’s treasury for the privilege. They, therefore, had a strong interest in bringing Webb and the Deba together to ensure that the EIC, the new governing power in the south after the forced withdrawal of the Gorkhas, understood what was required to ensure the smooth functioning of cross-border trade. There is clear evidence in the file that the British believed they had intelligence that, before their withdrawal, the Gurkhas had spread the message that the British would not tolerate “the special arrangements” which ensured that trade across the high passes ran smoothly. They would therefore try to stop the trade on which the Bhotias depended. As will become very clear, the Deba of Ticklakot also had a keen interest in this subject which made him eager to clarify future trading arrangements with some British authority.

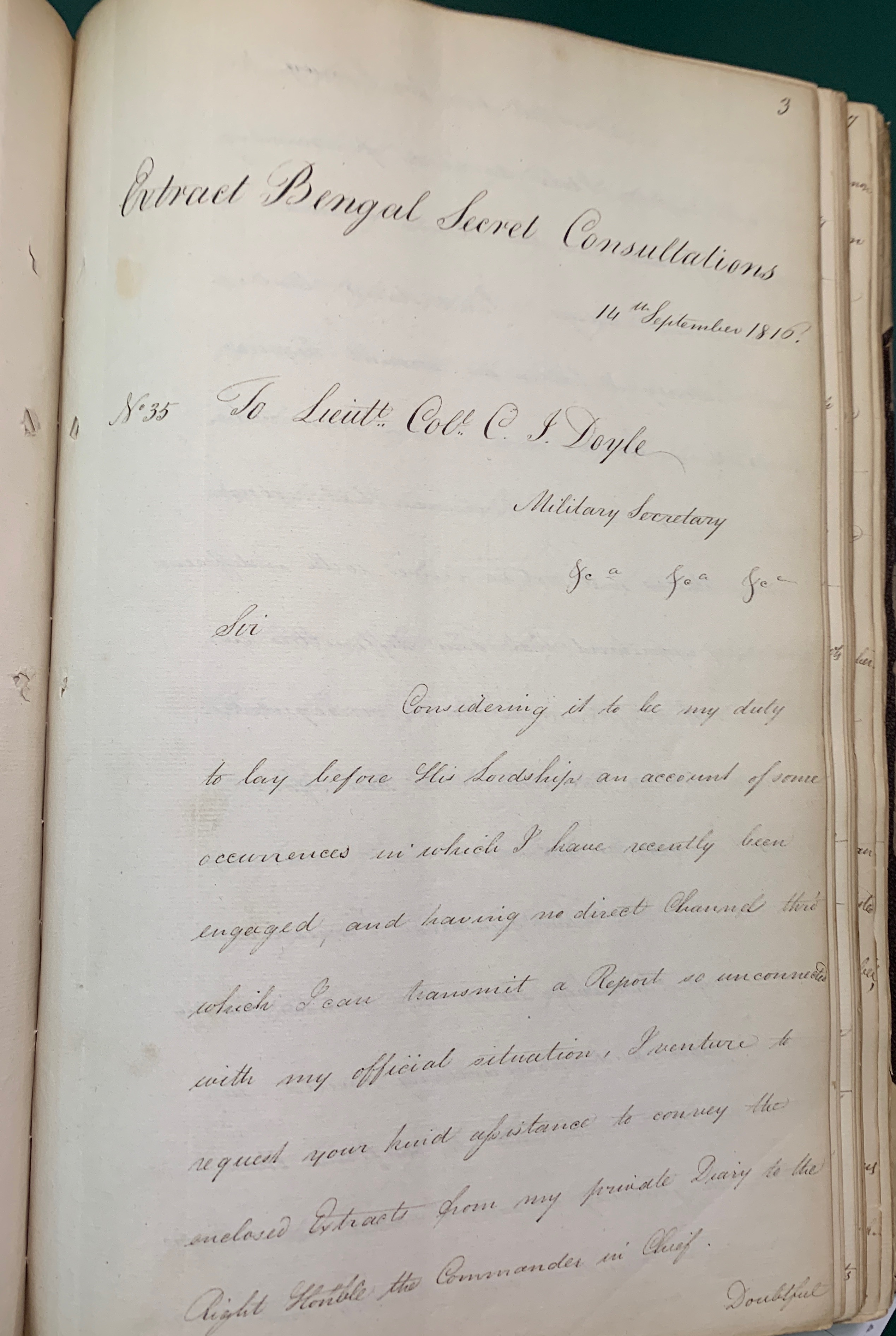

Below are the opening lines of the first letter in the file by date, addressed by Webb to the military secretary. They are highly significant. The first sentence indicates that he wants his submission, including his diary extracts, to go to Lord Moira, the first indication we have that the senior-most figure in British India at the time was aware of what Webb intended to achieve. Any doubts on that point are removed in the paragraph that follows.

This needs a close read. In particular, every word in this sentence is heavy with import: “On these matters you will judge best for yourself as you proceed.” I see the sentence as akin to a senior officer giving orders to a subordinate in these terms: “Look, I have no authority to order you to do this, but, you know what we would like, so use your initiative and do what you can but be careful. If anything goes wrong you will be on your own...”

Fortunately for Moira, Adam, and Gardner, they had in William Webb a man of rare talent as the mass of information he garnered about trading arrangements over Britain’s new northern frontier, including Lipu Lekh, demonstrate.

Webb’s decision to include an extract of Gardner’s letter shows that from the outset he wanted people to know that he was not some lone glory-seeker but had authority to try to contact the Deba and find out what he could about the state of cross-border trade. The extract confirms that the local traders were very worried about whether their new overlords would interfere with their existing trading arrangements with Tibet. The jealousy referred to in the second and third paragraphs refers to information the British had that the withdrawing Gurkhas had warned the locals that British oversight would bring cross-border trade to a halt, leading to great impoverishment. Webb argues that his incursion would dispel such jealously and lead to friendly relations.

[SC: after a lot of thought I have decided, in the interests of preserving some feel for the original manuscript, to retain the inconsistent spelling and the use of Capitals in the middle of sentences. At the time, the rules regarding Capitals were very loose and writers used them as a form of emphasis. Note also that all highlighting in Webb’s text is mine. Finally, the spelling of Ticklakot has been retained up to now. Tuklakot is less modern than Taklakot and has been retained]

“Sir,

Considering it to be my duty to lay before His Lordships an account of some occurrences in which I have recently been engaged, and having no direct channels through which I can transmit a report so unconnected with my official situation, I venture to request your kind assistance to convey the enclosed Extracts from my private Diary to the Right Honourable the Commander in Chief.

Doubtful how far I may have acted with propriety, I take the liberty of transcribing a passage of a letter from the Honourable Edward Gardner to my address. “I understand that much jealousy is felt on our account beyond our Northern Frontier and it has even been hinted to me by the Bhoteas that your Journey thither will not be received with indifference and they apprehend that some difficulties in their usual traffic might be the consequence. On these matters you will judge best for yourself as you proceed.”

Thus forewarned I considered that to pass churlishly along the frontier prying into its passes, and reconnoitring would be more likely to excite and to confirm than to allay the jealousy already kindled, and therefore to induce some friendly intercourse.

The next extract from the letter explains the key role of the zamindars in arranging the meeting, and particularly the key part played by Webb’s main guide, Ketee Booza, the chief zamindar of Dharma. The immediate positive response from the Deba indicates his enthusiasm for the meeting. It also suggests that he might have been sounded out earlier about the possibility of such a meeting. It is not hard to imagine representatives from both sides meeting to discuss the mutual benefit which might follow from a meeting between the Deba and Webb. Some details in the diary extracts point to this happening. Webb’s self-deprecating remarks in the final paragraph allow him to express the hope that his meeting with the Deba, “has tended to some degree to mitigate the jealousy, so insidiously excited by the Nepalese on the recently acquired Frontier”. It is worthy of note that there is no doubt in his mind that this emphatically includes Lipu Lekh.

I sent forward some of the Bhoteea Zemindars to Tuklakot, desiring them to state to the Governor the nature of my Journey and of my employment and to express a wish, if no objection existed, to be permitted to visit the Lake Manasrowar, which would also afford me an opportunity to pay my respects to him in person.

In consequence of the strenuous exertions of the Zemindars and more especially Ketee Booza of Dharma, the Chief sent a small deputation to meet me with a message expressive of his incapacity to comply with my request. I could have entertained no anticipation of a more favorable answer.

The messengers however suggested to me that if I felt any desire for an interview with the Deba, and would wait a few days for that purpose, he might probably be willing to give me that meeting near the Frontier. I thought it better to accept than to reject this proffered Civility, and the accompanying Extract from my Diary details the circumstances under which that meeting eventually took place.

The source from which it is derived must plead an excuse for the prolixity of narration, and I have to implore His Lordship’s pardon for having entered upon subjects remote from my immediate duty tho’ I trust it will appear to His Lordship that it was scarcely possible for me to avoid them. It would be great presumption on my part to suggest that any solid advantage has been derived from the intercourse, but I may still be permitted to hope that it has tended to some degree to mitigate the jealousy, so insidiously excited by the Nepalese on the recently acquired Frontier.

The short extract below indicates that crossing into Dharma from Byans over the Lebong Pass gave Webb the chance “to visit the source of the River Kalee.” This is a matter-of-fact statement but worth noting that in the opening section of the extract from his diary [see below], he refers to his tents being placed “near the Fountain of Kalapani, a place of religious resort, and considered by the natives as the source of the river of the same name.” As much as anyone, Webb knew that for Lord Moira, gaining exclusive control of trade over Lipu Lekh was an absolute imperative.

In any case, in the absence of a map attached to the Sugauli Treaty, the argument over river names is irrelevant as Nepal’s western border with British India was settled definitively by the pronouncement of Lord Moira, quoted in a letter to G.W. Traill, the commissioner for Kumaon, dated 5 September 1817, when he gave his reasons for rejecting Nepal’s request to transfer to Nepal the two villages of Koontee and Nabbee. Webb and Traill were both consulted and were strongly supportive, with the latter correctly observing that “any decision taken otherwise would have resulted in the creation of a constant source of conflict between the two states, in respect of transit duties, etc., on the trade leading to the Tibetan marts through Lipu Lekh.”

[For full details and references, see Part 3 of my article, ‘The Gorkha War and its aftermath’]

The last word in the extract below is “Bootan”, a word that appears many times in this file. Dr Shekhar Pathak, a distinguished historian, writer, and native of Uttarakhand, has helpfully explained this to me as follows. The highlands of Kumaon were known through the sub-regions as Bians, Johar, Painkhanda, or Taknaur. Bhot/Bod/Vod was used for Tibet and Bhotiya for Tibetans. As a frontier region with Tibet, the EIC officials too started using the Bhotiya term for these highlanders. Later this word was frequently used and no one was concerned about its real meaning. So most of the EIC officials and other travelers started calling these highlands Bootan or Bhootan.

No opportunity offered of instantly transmitting a statement of the above occurrences and since that period I have visited the source of the River Kalee, and with imminent peril, crossed the Snowy Ridge separating Beeans from Dharma by the Pass of Lebong. The extreme labour and great difficulty of respiration experienced in the last undertaking has occasioned a general sickness in my camp. I hope I can get the whole party under Shelter tomorrow, and to accelerate their recovery as well as to wait till the season shall be more advanced. I propose remaining stationary for some time in Dharma.

Should the general sickness not abate, I shall think it my duty to return to Almora at an early period but if, according to my hopes, rest brings about a speedy recovery, your reply to this letter will find me still in Bootan.

The final extract from the covering letter below is also of interest. What is written in both paragraphs suggests Webb’s intimacy with the Governor-General, John Adam, and Edward Gardner which must have been based on some consultation, or possibly even a meeting, between them and Webb before he departed on his trip. As indicated earlier, the Mart of Gurdan probably refers to Gartok which was by far the biggest trading mart in that part of Tibet. In contrast to smaller marts like Tuklakot, traders from Ladakh attended Gartok and had exclusive control over the prized pashmina cloth. “The Tartar Viceroy” refers to the Viceroy of Gurdone who was the Deba of Tuklakot’s senior. As will emerge later, the Governor-General and his two senior subordinates lost their nerve to back further cross-border investigations by Webb so there was no possibility of them agreeing to his admirably bold proposal.

The last paragraph again underscores that the highest priorities in Lord Moira’s mind were trade and the profits that he hoped would flow from it. The personal nature of the wording suggests the fulfilling of a promise by Webb.

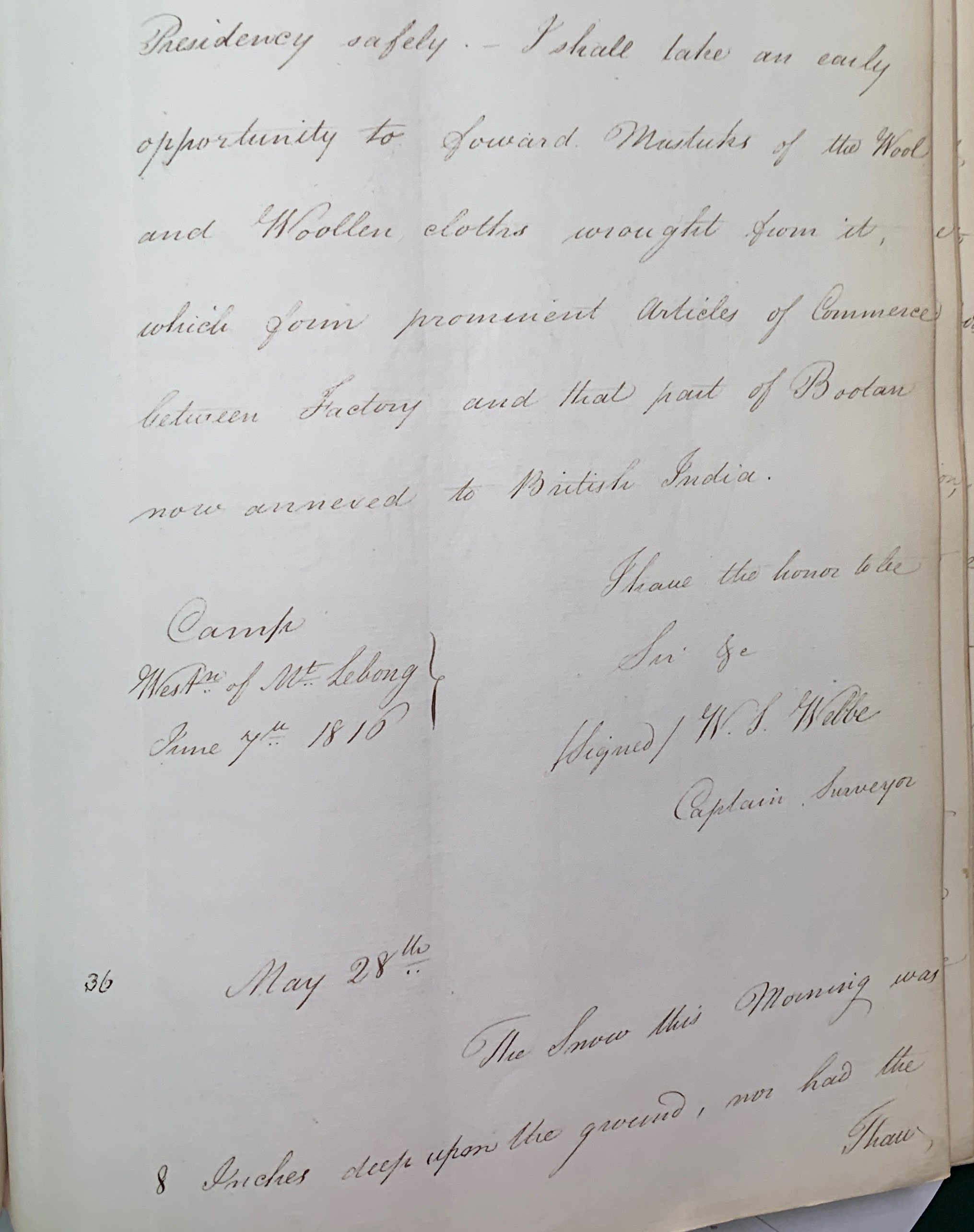

If it should be deemed a matter of importance to acquire such information as my abilities are equal to collect respecting the Mart of Gurdan, I am of opinion that a brief message from His Lordship to the Tartar Viceroy might give me access to that city at the period of the annual fair, and that some account of Lehdak might be collected from the Merchants resorting to it as well as an actual experiment made, if such were desirable, of the value of Pearls and Coral in that market, both articles being of small bulk and easily transportable by Dawk. [to transport by a relay of men or horses]

I enclose for His Lordship’s inspection a specimen of the gold dust of Tartary and one of the Damasker now current at Lehdak. I have also forwarded to your address a box containing botanical specimens of which you will find a list enclosed. I hope they will reach the Residency safely. I shall take an early opportunity to forward Musluks of the Wool and Woollen cloths wrought from it, which form promised articles of Commerce between Tartary and that part of Bootan now annexed to British India.

I have the honour to be, Sir

Signed, WJ Webb

Captain Surveyor

Camp

West of Mt Lebong

June 7th 1816

It is not possible in an article such as this to give every line in a 70-page file but the extended extract from Webb’s diary below gives the main details about the arrangements for the first very important meeting between Webb and the Deba.

The stage management of the meeting is impressive. Nothing was left to chance. No one could feel that they had lost face. Clearly, emissaries from the zamindars and the Deba had worked in close consultation during the planning to ensure that everything ran smoothly and properly, no mean feat in such a very remote spot. As will be seen, this meeting laid a solid foundation for the two highly productive meetings in the days that followed.

I have highlighted three particular points, starting with “the Fountain of Kalapani” which locals considered as the source of the river of the same name, and how the conversation was facilitated using three interpreters. The third point highlighted is what preoccupied discussion at this first meeting.

Webb records that the Deba had drawn up a list of questions about the recently concluded war between the forces of the EIC and Nepal. It is not surprising that the Deba was anxious to hear details of events about which he would only have heard vague and possibly inaccurate accounts. Nor is it surprising that Webb used the opportunity to put across the Company’s views on the reasons for the war and its outcome.

The meeting ended on what could reasonably be described as a very fraternal note which set the tone perfectly for what was to follow.

[SC: Based on consultations I had with friends who I knew could guide me on matters Tibetan, I have inserted some comments in brackets which I hope readers will find both interesting and instructive.]

May 28th.

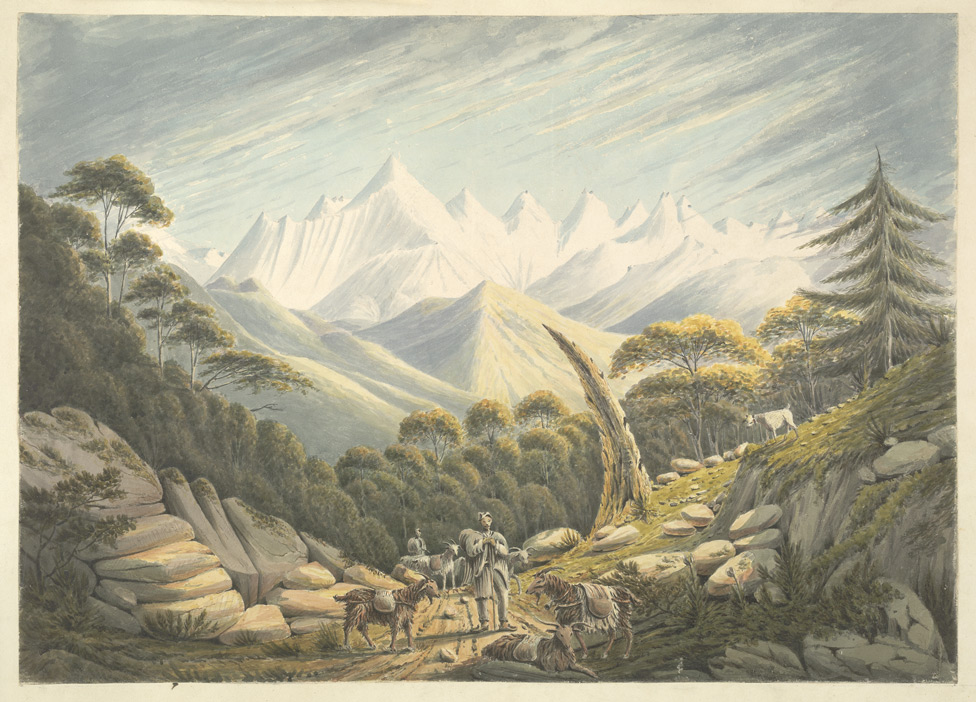

The snow this morning was 8 inches deep upon the ground, nor had the Thaw become sufficiently effectual to admit of our proceeding towards Kalapani till one o’clock. The road even then been so inconvenient for walking that I was fain to avail myself, for the first time, of the assistance of a yak. The animal led by a Bhotea carried me the greater part of the distance, without making a single false step. The road lied along the edge of the Kalapani river, which tho’ stony was very passable for horses. During the march we twice crossed the stream by spar bridges,[SC: consisting usually of round timbers/tree trunks lashed together] and although one of them consisted of only a single plank, the yaks passed over leisurely indeed, but without faltering or exhibiting any appearance of being appalled by the rushing of the torrent below. The whole distance was 3520 fathoms, at about a mile short of Kalapani we passed a tepid spring on the right bank of the river, the temperature of which about 8C, its water appeared to me not to possess any mineral taste. Juniper bushes were plentifully scattered on the path, a few trees were observed and these were exclusively alpine and Bhajpule.

The hills on other hand were of naked rock, the snow still rested at about 50 feet above our path, small parts of the same occasionally concealing the channel of the stream. My tents were placed near the Fountain of Kalapani, a place of religious resort, and considered by the Natives as the source of the river of the same name. [SC: by my reckoning, the camping spot must be close to where the Indian Army camp is located today] The Deba had requested I should camp upon this spot, the ground he occupied being concealed from view by a jutting rock about half a mile further in advance. That Chief had sent some of his people to greet my arrival who were also the bearers of a Teeafub [SC: meaning uncertain] consisting of a joint of Mutton dried in the Tartar manner, a skin of Butter, a plate of tea and a dish of Suthoo, a Sweetmeat composed of Barley meal, ghee and Sugar. [SC; ‘Suthoo’ is the usual Hindu and Urdu word for tsampa. Webb is describing the Tibetan delicacy known as ‘thü’, but misses out the crucial ingredient of powdered dried cheese!]

After some negotiation of the Chief in the first instance objecting to return my visit, it was at length settled I should in the first instance wait upon him, and that he should return the compliment on the following day. I lost no time in repairing to his camp which was about a mile distant. The accommodation of the chief was a double poled tent of woollen cloth sufficiently capacious but the materials of too slight a texture to afford much defence against severe weather. Two or three small tents were pitched near it.

The Horse of his Troop were grazing around, generally small, compact and well made, their coats exhibiting no appearance of having ever suffered the torture of the Curry Comb – intermixed with these were a few very fine mules which I was told are used only for carrying burthens [SC: old form of burdens]. The Deba’s Secretary accompanied by some others met me at the precincts of his camp and conducted me to the Tents of their Chieftain.

He was seated on an Ottoman cushion covered with a gaudy Carpet at the furthest extremity, but rising at my entrance he advanced a few paces and shook hands with me. The others in the tent took off their caps and bowed. The Bhoteeas who had accompanied me initiated this latter move of salutation, presenting their muzzurs Turbans in hand.

The Deba’a son was sitting on a silk cushion on his fathers right hand, a silver seat he placed for me on his left, for which ever I was permitted to substitute my chair. The rest of the party ranged themselves along either side of the tent, sitting down without ceremony or signal from the Chief. Our conversation was duly carried on through the medium of no less than three interpreters, the first rendering my Hindustani with the language of Bootan, the second into the dialect of the Bordu and the Deba’s Secretary into the more polished language of Oochoong. Of which place the Deba is native. I strongly suspect however this last interpretation was employed rather for ceremony than from necessity.

[SC: “Bordu” denotes one or other of the many Tibetan dialects that are spoken in the borderlands. “Oochoong” refers to Ütsang, which collectively refers to Central Tibet and is still widely used. It is divided into three parts. Ü is the more eastern part, centered on Lhasa, and Tsang is the western part, the main centers of which are Shigatse and Gyantse. Nearly all the provincial governors of Tibet under the Dalai Lama’s government came from Central Tibet, where the various dialects spoken – particularly those of Ü – are considered to be the most refined. It is significant that Webb regards the last step of translation from a border dialect of Tibetan to the “more polished” Ütsang dialect, as being “rather for ceremony”, since the Deba probably understood the provincial dialect but was pretending to be too refined to do so. The fact that the Deba was a native of Ütsang confirms that he must indeed have been a Central Tibetan aristocrat.]

Previously to detailing our conversation it may not be considered intrusive to describe the person and costume of Deba Butong, the Tartar or Chinese Governor of Tuklakot.

He is apparently about 40 years of age, of middle height, stout and athletic in form. The countenance tolerably fair, placid and agreeable, he speaks in a quiet tone of voice, with a grave and measured articulation, his deportment dignified and sedate, never appearing to notice with curiosity objects which must be novel to him or condescend to make enquiries respecting them.

He was dressed in a long robe of buff coloured damask silk, girt round the waist with a crimson sash of the same material, on his head he wore a hat, similar in form to an English one excepting that the crown was round. The whole was covered with a rich cloth of Silver lace, the crown was surmounted by a small Chrystal Globe from which as a center hung pendant a fringe of orange coloured Silk about a span in depth. He wore pendants in both ears consisting of a large irregular shaped Pearl strung with alternate beads of Tourmaline and wrought gold. [SC; this is a long pendant earring, called ‘along’, worn by Tibetan officials] In his sash was thrust a Chinese pencase of Steel inlaid with Silver which with its Inkstand were badges of his Office. Behind his Ottoman was placed his Couch covered with Leopard skins and before him a Chinese lacquered desk, a silver tobacco pipe gilt and ornamented with fillagree work, his teacup of the knot, or globular excrescence of the Klumea Tree which takes a high polish, and resembles in appearance Saltin Wood but having a dark waving vein and on either side a bag of Rupia leather, one containing sweetmeats and the other tobacco. A straight two edged sword was laid by his side, and half his cushion was occupied by a Shuck dog which he occasionally patted. No part of his head appeared to be shaven, his hair was plaited into long tails reaching to his loins. [SC: if he had been a Chinese or Manchu official the front of his head would have been shaven and he would have had a single plait] The whole party wore stout boots of Rupia leather.

At the furthest extremity of the tent stood a domestic bearing a huge brazen teapot containing about a gallon. Its contents warm and mixed with Ghee were distributed without any distinction to the whole party and was to my taste extremely nauseous and unpalatable.

After a few introductory compliments in which the Deba inquired after the health of the King and of the Governor General the conversation led to the occurrences of the late war with Nepal and its termination. This subject occupied the time till near sunset the Chief preparing numerous questions, all of these being replied to, he remarked that according to my account the Nepalese were certainly the aggressors. It was well that the event had decided on the side of justice offering his congratulations to the success of the British arms. On my rising to take leave he said that he would not suffer me to depart without expressing his regret at the necessity he felt to with-hold his consent to my visiting the lake of Manasarovar as the prohibition was general and unqualified.

The Viceroy of Gurdon who had disobeyed this order in favour of Messrs Moorcroft and Hearsay, had been removed from his situation with disgrace, and summoned to Oochung where, in all probability further punishment awaited him.[SC: In July 1812, Moorcroft and Hearsay, dressed up as Indians, had entered Tibet illegally to visit Lake Manasarovar with, as indicated, likely dire consequences for the Viceroy of Gurdon] He begged me however to believe that the prohibition was not directed especially towards the English but had in point of fact been caused by the incursion of the Gorkhas. He expressed a hope that by quitting Tuklakot to meet me in deviation to the general rule, he had given me sufficient proof of his own favourable disposition towards my nation and that I would so far give him credit as to believe him incapable of saying one thing and meaning another.

To this I replied that obedience to supreme authorities was a duty early impressed upon the mind of every soldier and that however his refusal operated to my individual disappointment, I was bound to respect his and admire his integrity and that now being aware of the consequences to him which my visit to the lake might be attended, I requested him to forget that I had preferred a solicitation which I no longer felt serious to repeat. The Deba as if he felt relief from a disagreeable topic and having fixed the hour for his visit tomorrow I took leave.

As with all visits, the question of presents can often be sensitive but Ketee Boora, the chief zamindar of Johar, had a solution ready to hand. Indeed, it would seem that he suggested the need for gifts in the first place. The Deba was clearly delighted with what he was given.

May 29th

It had been suggested to me that some presents would be expected and upon ransacking my scanty store, I could find nothing suitable excepting two silver goblets which had not been used. These however seemed hardly sufficient, but Ketee Boora, having heard of my distress very civilly offered to furnish me with a few yards of broad cloth from his investment, which reasonable supply enabled me to receive my visitor as I wished.

I had pitched my tents together so as to afford accommodation for the whole party and about Noon the Deba arrived on horseback with his small troop. Having offered him refreshments of tea and sweetmeats I presented him four yards of scarlet broadcloth and the silver drinking cups. He appeared particularly pleased with the latter and admired the beauty of the workmanship.

In the next extract, Webb raises two subjects that reveal how the zamindars used this meeting to protect and promote the interests of their people and used him to promote their concerns. On both subjects, the Deba gave a very positive and forceful response – “there would be no interruption”. His commitment to take firm action against incursions from Nepal into what was now the territory of the EIC would have been welcome news to Lord Moira and his team. His commitment to communicate to his superiors at Gurdone and to the other frontier marts details from the meeting was another positive for Webb. Webb’s threat to bring in the military in the event of any interruption might have exceeded his authority but it must have sounded suitably impressive at the time. On the plundering by the Jumlee raised by the zamindar of Byans, the Deba stated that he was aware of this, and the news pained him, but since he had just heard of the outcome of the recent war, it might be that the news had not reached that remote area.

There were two subjects which though perfectly distinct from my official situation I thought it proper to touch upon and hope that in this instance I did not act erroneously. The first was the jealousy which was known the Gorkhas endeavoured to eveite and which it was feared might occasion some interruption to the commercial relations between Bootan and Tartary.

The second was stressed upon me by the Zemindars of Beeans who had been severely plundered last year by their neighbours of Jumlee and the latter again threatening to repeat their incursions it was their general opinion that the influence of the Deba was sufficient to prevent such an occurrence. Their great desire to effect a meeting with the Chief and myself derived itself principally from this object. I introduced the first, therefore, cautiously and without seeming to doubt what would be the nature of the Chief’s reply nor did he disappoint this apparent confidence but declared without hesitation that no interruption should take place and the usual trade at Tuklakot and that as in the regular course of duty he should communicate to his superiors at Gurdon all the occurrences of our meeting. He felt confident that he might include also the other Marts on our frontier.

The second topic had been already brought forward by a petition of the Zemindars proffered to the Deba, in my presence, rather unexpectedly. To this I ventured to add that such conduct on the part of the Vassels of Nepaul would be a gross infraction of the Treaty recently concluded and that as the English did not suffer insults patiently the consequences might even render Bootan the scene of military operations. That the occurrence of these was always to be deplored and that as the presence of Troops in that quarter could not only interfere with the peaceful avocations of commerce but consume their supplies of grain on which the very existence of the inhabitants of Taklakut depended it seemed that he himself was scarcely less a party concerned than the Boras who had addressed him.

He answered that he was already appraised of the circumstances mentioned and that they

had occasioned him great uneasiness. That feeling convinced from the new Character my statement had given to the Nepalese War that no sinister views were entertained by the English against his government that he should think it his duty to expostulate and protest against such conduct on the part of Joomlee. He added however that I had communicated to him the first intelligence which might be considered authentic of the conclusion of peace which he also should not fail to promulgate thinking it possible that since at this moment no Gorkha agent resided in Jumlee, correct intelligence of this event might not have reached that remote Pergunnah.

The Deba next raised a subject that was central to the concerns of both him and the zamindars. He explained that all these pergunnahs paid revenues into his treasury, which had continued under Gorkha rule, and, essentially, he wanted to know if the British would be happy for these arrangements to continue? Clearly, the Gorkhas had spread the word that the EIC would not be happy. Fortunately, the zamindars had already told Webb that Edward Gardner had directed them to continue the payments. This enabled Webb to give a very polished and confident answer to the Deba’s question. He gave an equally impressive answer to the follow-on question about the deployment of troops to collect the rents due to the EIC. The Deba’s response was just as polished and statesmanlike.

In the last paragraph of the extract, as will be seen from the diary account of Day 3, Webb amassed a large amount of valuable information “respecting trade on the border” from his discussions with the Deba. This was his central mission. Nearly all the information would have been new to Lord Moira and his senior officials.

The Chief then observed till within the last twelve years Beeans had been exclusively attached to Tuklakot and that I would not have remained so long in Bootan without learning that certain Revenues had been paid into his Treasury for time immemorial by Choudars, Beeans and Dharma which had never been interrupted even during the periods of the Gorkha government of Kumaon. He wishes to know, therefore, whether any alteration was projected in this respect. The Zemindars had previously told me that they had been directed to continue these payments by Mr Gardner and I therefore replied that having already explained the nature of my own office, the Chief must be aware that in giving a direct reply to this question, I should be guilty of great presumption but that if he really enquired my opinion as an Individual I conceived that the conquered Pergunnahs had reverted to the British government exactly as they stood under that of Nepal that I understood no orders had been issued tending to diminish his receipts and that adverting to the general character of the English Government they were not accustomed to abolish ancient usages to the prejudice of their friends and allies. The Chief appeared satisfied with my reply.

He next inquired what number of troops would be employed in collecting the revenues of Bootan; whether they would be sent periodically for that purpose or remain stationary in the Pergunnahs. I answered that oppressive Governments only find it necessary to make their Collections at the point of the Bayonet but as under the British rule the Zemindars were contented and, it was very rarely necessary to employ the military in realizing their revenue adding that it was not to be supposed Bootan would form an exception to this general rule. The Deba bestowed some compliments on a state so careful of the interests of their subjects and said that in this respect we imitated the Custom of China.

The remainder of our conversation was desultory consisting principally of enquiries on my part respecting trade on the border, the actual degree of dependence upon China proper and other general topics, to all of which the Chief replied with great politeness without any apparent reserve. I shall subjoin the information I gained under one general head but I have thought it necessary to detail the previous subjects more minutely because I thought that they were discussions removed from my Employment some of which it might have been perhaps more prudent to avoid.

These last lines of the diary entry covering Day 2 speak for themselves, as do the opening lines covering Day 3. ‘Brotherly’ respect for each other is openly declared.

The Chief remained with me near five hours, sending for his pipe and large teapot, as seeming to consider me but an indifferent preparer of that beverage.

In spite of his reserve, I noticed that the glitter of a brooch set with some small Brilliants ever and anon excited his attention and though the value of the trinket was rather greater than it was quite agreeable to disperse of on such an occasion I felt so much pleasure with the manner and behaviour of the Chief that I determined to gratify him with it and when he rose to take his leave I told him that I had already thanked him for the trouble he had taken in coming to meet me and for the pleasure I derived from receiving him as my Guest but that he must not suppose me insensible of the compliment he had paid me an Englishman, by trusting himself among us with a few unarmed attendants, just at the period when every exertion had been made to prejudice him against my countrymen and my government, concluding by requesting his acceptance of the brooch as a token of remembrance. He was evidently much gratified by the present and requesting me to halt another day fixed the 31st for his return to Tuklakot when I also should be at liberty to pursue my travels.

May 30th

About noon the Deba sent persons to conduct me to his tent, regarding me to favour him with another visit. When we were seated he apologised for the smallness of the present he was about to offer, as he had left Tuklakot hastily and without having made provision in this respect. He then delivered me a small handkerchief of flowered silk, a little gold dust and threw across my shoulder a course Scarf of China grass cloth. [A typically Tibetan ceremony of valediction] He then repeated his intention of writing to the Viceroy of Gordon assuring me that if in the course of my journey I should pass near the capital of that Chief and should be desirous of an interview with him, that I might confidently rely upon him giving me the meeting. After hours of conversation on a different subjects, we parted with mutual protestations of regard, the Deba desired me to consider him henceforth as a brother.

This next part of the article gives selected extracts from Webb’s diary from Day 3. The detail and range of the information listed show just how forthcoming the Deba had been in sharing his knowledge with Webb. It also bears further witness to the great respect the two men had for each other. The intense focus on trade speaks for itself.

I learned from the Deba that 130 years had lapsed since the perfect subjection of the Provinces on our border to China which he calls Geeal probably the same as Kiang an extensive province of China, where the Emperors Court was held previously to its removal to Pekin which last name the Deba does not recognise. The Imperial orders reached Tuklakot via Jangsum Oochoong (or Lafee), Farm and Gurith, [SC Note: I am uncertain about the transcription of the last two words] of which last Tuklakot is a dependency. The Expresses are carried by Horsemen of whom there are relays upon the road in 45 days from the Emperor’s Court to Oochong, [Lhasa] thence to Gurdon in 15 days and lastly to Tuklakot by a single horseman in 6 days. [SC Note: In practice probably 3 days] The supreme control of the western provinces is vested in the Deba of Oochung. The Deba of Gurdon also possessing considerable authority. Deba being the Tartar title for Viceroy, Governor, we understand what was meant by former travellers when they state that Thibet is governed by the Deb Rajah. The name Tibet is not known here.

The Chinese empire extends in a westerly direction 5 days journey to the westward of Gurdon but does not include Lehdak, though I am informed but even this city pays a small revenue to Oochoong. [SC: This is a reference to the Lopchak tax/tribute paid annually to Ütsang as part of the settlement after the 1680-1684 Ladhak-Tibet War] I am rather inclined to think, it is more properly an annual gift to the Chief Lama or pontiff . Wherever a Deba resides a Lama is also appointed, the first being the civil and military governor, The second a Prelate to whom spiritual concerns are intrusted. Both authorities are occasionally relieved or transferred from one station to another. The Deba of Tuklakot is entering upon the fourth year of his governance. The Viceroy of Gurdon has been still more recently appointed.

I could not learn how far the Chinese authority extends to the northward. It does not appear that Caravans of Merchants from this part of Tartary resort to China proper or indeed that any regular Trade is carried on. Various manufacturers of China are brought to Oochoong, as silk and petty wares and from the latter place the wealthier inhabitants of Tartary procure several articles of dress or luxury, but the aggregate derived is so small as scarcely to merit the denomination of Commercial Trade.

The principle Marts near the recently extended British frontier are Gurdon, Durchung [on the bank of Lake Mansurowa] and Taklakot, the distance between the two last not exceeding 15 Miles or two days journey for laden animals.

Gurdon is a continual Mart, but it should appear that in the month of September an annual fair is held which is resorted to by the Merchants of Ledak and Cashmire and that at this period very extensive commercial business is transacted. The superior value and greater variety of articles brought to Gurdon, necessarily limits the Trade by Barter which is almost exclusive at the other Marts and renders a circulating medium necessary. The Coin in ordinary use is the Jumashee struck at Ledak, from silver bars or ingots imported from China. Gold Dust also supplies the place of money though strictly speaking I think it should more properly speaking be considered an article of trade.

Dhurchung is probably situated up on the high western road and serves as an entrepot between Oochoong and Ledak. The individual merchants pitch their tents, and a market of this kind continues from June to October. I have not yet received the volume of the Asiatic Researches which contains the account of Mr Moorcroft’s tour, but as I conclude that that Gentleman visited Durchung and can speak from actual observation I refrain from detailing information acquired at a distance which cannot probably be so correct.

Taklakot is also in a limited way a continual Mart, that is for Salt and Borax. A Fair also is held here during the months of October and November at which season the whole vicinity is covered with the Tents of Merchants from every direction.

The principal articles bought from Tartary are Wool, Woolen Cloth and gold dust to which may be added Tea and goods from Oochoong for home consumption.

The Deba computes [SC: Modern speech, calculates] that from 15000 to 20000 Fleeces are annually brought to the markets of Gurdon and Taklekot, but says that the goat’s hair used in the manufacture of Shawls is not to be met with at either place, Lehdak enjoying an almost exclusive monopoly of that trade, nor could it be in the Deba’s opinion be easily deviated from the present channel. [SC Note: This would have been bad news for Lord Moira given his letter to London, dated 20 July 1815, in which he had told the Directors that control of Kumaon would almost certainly give the EIC exclusive control over the shawl-wool trade.] The Wool bought at Taklakot is delivered by the individual proprietor of flocks, it is neither picked or sorted. As I have not yet seen a Fleece, I am unable to form any estimate of their average weight and as they are generally obtained by Barter, I am equally at a loss respecting the market price but from a rude comparison I think the latter may be taken at about three fleeces for the Farrukhabad Rupees.

Gold dust would readily proportion to the demand. It is delivered in small parcels laid separately in a rag and one of these is called a Fitang. I found the contents to be 81 grains Apothecary’s Weight. The Grains of Gold are of a large size, and pale yellow color apparently containing but little drops. Supposing the intrinsic value to be the same with foreign Gold in Bars, the London price of which is now quoted at £4. 3 per Ox the Fitang should be worth about 14.01/4 English Money but the price demanded here is no less than 8/8 Furruckabad Rupees

If my information be correct, there is a distinction of the Gurdon Market which I have not yet mentioned that goods are deposited in the custody of wealthy Brokers instead of being delivered by the individual proprietor.

I could not obtain any satisfactory account of Lehdak, and as more favorable opportunities may occur during my Journey I think it better to wave that subject altogether for the present.

The Deba thinks that Pearls, Coral, the Shell called, Sunteh, and broad cloth to the amount of in all, 8000 or 10000 Rupees annually would find a good market at Tuklakot. But the experience of the Bhoteeas is certainly unfavourable to the latter article and though great steps be laid upon Pearls and Coral by all parties actual experiment is the only criterion by which we can finally decide.

I was informed that in all matters of ordinary import the Deba of Gurdon was competent to act from his own authority and upon proposing as an instance, “an arrangement respecting Commercial intercourse with Hindustan” I received a tacit assent accompanied by an observation that it would be unbecoming as a Subordinate Officer to give a direct reply to the question. [SC Note: such trade had stopped during the Gorkha occupation of Kumaon]

At this point in the file, the page above appears, headed, “Statement of annual revenue paid by the Zemindars of Dharma and Beeans, to the Chinese officer stationed at Tuklakot. Kaudum Rolle/Kotte and Choobingkot.”

There is no note on the page to indicate who produced it but it is a fair assumption that Webb himself must have done so based on information given to him by the zamindars. They would have had this sort of information in their head. See note in the bottom right of the page where it says, ”The above statements were collected from the Zemindars of Bootan. I have no reason to suppose that Deba was informed that any such enquiry was instituted.”

All the Byansi villages are listed so it is likely that this was compiled before, following a request by the Nepalese, the EIC handed Changru and Tinkar over to Nepal. This transfer took place in September 1817.

It is clear that the zamindars of the villagers of Dharma paid annual revenue to the authorities in three places – Taklakot, Kandumkot, and Choolingkot, and each Dharma village had their own assessment of what each was supposed to pay – in rupees, maunds of grain and measures of cloth, though the villages of Beeans paid taxes only to Taklakot, in the form of cash rupees, maunds of Ooa [a type of high altitude barley] and, instead of cloth, yak loads of beams-rafters, posts and planks for building, and basket mats. This was the price that the Bhotiyas had to pay to be allowed to cross into Tibet on their annual trading trips. They also had to pay rent for their houses and land on the southern side of the frontier, a requirement which particularly irked some senior British officials.

On the names listed at the top of the page beside Taklakot, Dr Shekhar Pathak has very helpfully commented as follows:

“I could not trace the names. They may be smaller locations near Taklakot. Purang/Taklakot was the major mart meant for Indians and Nepalese. Lipu Lekh was used by Chaudans and Bians traders, Darma traders used to cross Limpiya and Mangsya passes. Traders from Johar used to reach their mart Gyanima after crossing three passes (Untadhura, Jayanti and Kingri Bingri) and from there used to come to Taklakot. Villagers of Chhangru and Tinkar used to cross over the Tinkar Lipu to reach Taklakot.

I have found the name Khardam/Kardam in the Survey of India Maps of 1851, 1907 and 1916. It may be Kandum. Its location is in the upper catchment of Karnali. Choolingkot may also be a smaller mart nearby. There were some inner marts in Kumaon like Neykorchu near Kuti village, Bedang in Darma and Kalapani in Bians.

Lipu Lekh was also the pass for Chaudans traders to reach Taklakot. Naturally they paid taxes to the Taklakot authority but I could not understand the meaning of '8 MOSS of Boa Johar'. This may be a tax of some kind, perhaps paid in the form of some crops.”

By way of further explanation, when Britain annexed the province of Kumaon at the end of the war, it was given the legal status of a Non-Regulation Province. To quote Bergmann, “In some places, in order to effectively deal with changing local contexts, the colonial government suspended the full application of imperial law, complex bureaucratic procedures and separation of powers. Non-Regulation provinces such as Kumaon were ministered not by the rule of law but rather by ‘discretion or executive interposition’. In practical terms this meant that the commissioners of such provinces were much more powerful than their counterparts in the regulated areas.” [“Confluent territories and overlapping sovereignties: Britain’s nineteenth century Indian empire in the Kumaon Himalaya”, Christoph Bergmann.]

The system worked well in everyone’s interest, and in ‘The Gorkha War and its aftermath’, I give one example of what happened when the British tried to change the arrangement. In brief, the Deba and the Bhotiyas conspired together to force the EIC to abandon implementation of the changes proposed. To quote, “thus were the senior officials of a great imperial power in its pomp made to bend to the will of Tibetan officials and Bhotiya traders.”

The extract from Webb’s diary concludes with eight pages of detailed descriptions of plants and trees in the areas through which Webb travelled.

After the diary extract comes the significant letter, dated 16 November 1816, signed by J Adam, Secretary to the Government of India, giving the official response to Webb’s submission dated 14 September 14, 1816. [Full transcription below] The “far from disapproving” assessment in the second paragraph is probably best understood with reference to the following paragraph which gives not only strict instructions to Webb to cease all communications with the Deba, or with any other Chinese official, but also to suspend what he was doing at that time and to move out of the area. The reason given for this harsh line is that it has “become peculiarly necessary to observe the strictest caution in all our proceedings on the Frontier of Chinese Tartary and in our intercourse with the Officers and subjects of that Government.”

So why the loss of nerve? What has changed since the encouragement given to Webb in the letter from Edward Gardner? Two possible reasons spring to mind which might have been felt more strongly by the Board of Directors of the EIC in London. China had long standing suspicions about British plans in the Himalaya. However mistakenly, at this time, Britain believed that since 1792 Nepal was no longer an independent country but a Chinese tributary. Therefore all dealings with Nepal had to be assessed against the need to stop China from intervening on Nepal’s behalf in response to British plans and actions. Probably weighing even more heavily on the Board of Directors at the time was fear of upsetting the always fragile position of the Company’s trading position in Canton, particularly given the rich potential for profitable direct trade with China through that port.

Against that background, ‘far from disapproving’, can be taken in a much more positive light. The ‘hereafter’ in, “on the contrary exclusively of the other advantages, it may be the means of leading to hereafter”, indicates a hope that Webb’s work may yield more benefit in the future. Full tribute is paid to the way that Webb conducted his relations with the Deba. The letter finishes by assuring Webb that all his expenses relating to his gifts to the Deba will be repaid in full. [SC Note: Not included in article]

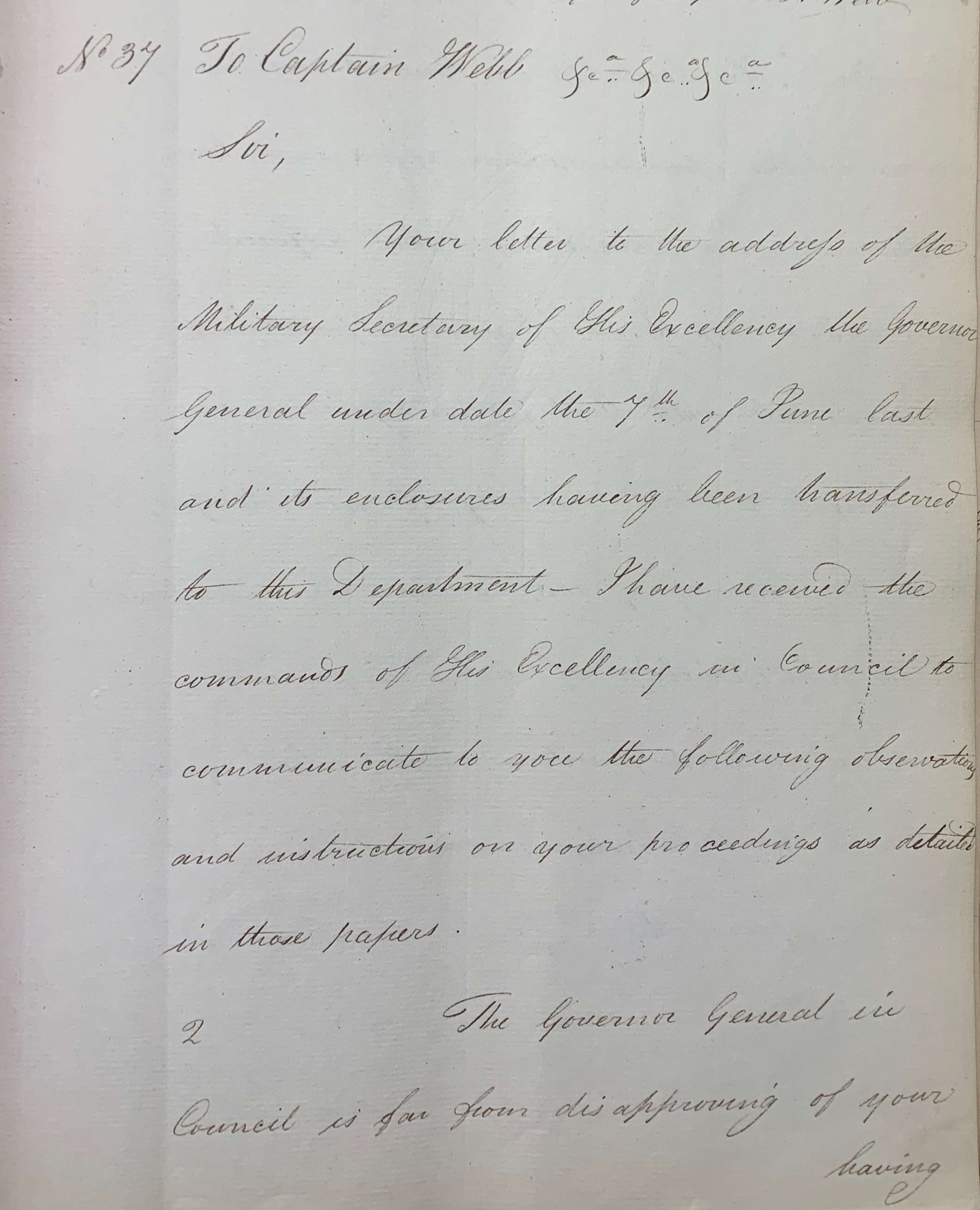

To Captain Webb

Sir,

Your letter to the address of the Military Secretary of His Excellency the Governor Genera under date 7th of June last and its enclosures having been transferred to this Department, I have received the comments of His Excellency in Council to communicate to you the following observations and instructions on your proceedings as detailed in those papers

2. The Governor General in Council is far from disapproving of your having opened communications with the Deba of Tuklakot and having interchanged visits and civilities with him. On the contrary exclusively of the other advantages it may be the means of leading to hereafter. His Lordship in Council entirely agrees in the opinion which appears to have influenced your proceeding, that a frank and cordial expression of your disposition to communicate with that personage was far less likely to produce jealousy of your designs, than the Journey of your survey unaccompanied by the manifestation of such a disposition. The caution and prudence with which your discourse to the Deba was conducted merit also the approbation of His Lordship in Council.

3. I am directed to intimate to you that in consequences of circumstances you have recently come to the knowledge of the Governor General in Council, with relation to the proceedings of the officers of the Chinese government, it has in the judgement of His Lordship in Council become peculiarly necessary to observe the strictest caution in all our proceedings on the Frontier of Chinese Tartary and in our intercourse with the Officers and subjects of that Government. His Lordship in Council would wish therefore that until you shall receive a further intimation on the subject you should endeavor as much as possible to avoid even the most limited intercourse with the Country and people beyond the Himmalek. It will even be expedient to suspend the prosecution of your survey and researches in that quarter for the present and to occupy your time immediately on completing other parts of the work assigned to you which may be pursued without leading to any communications of the nature above referred to.

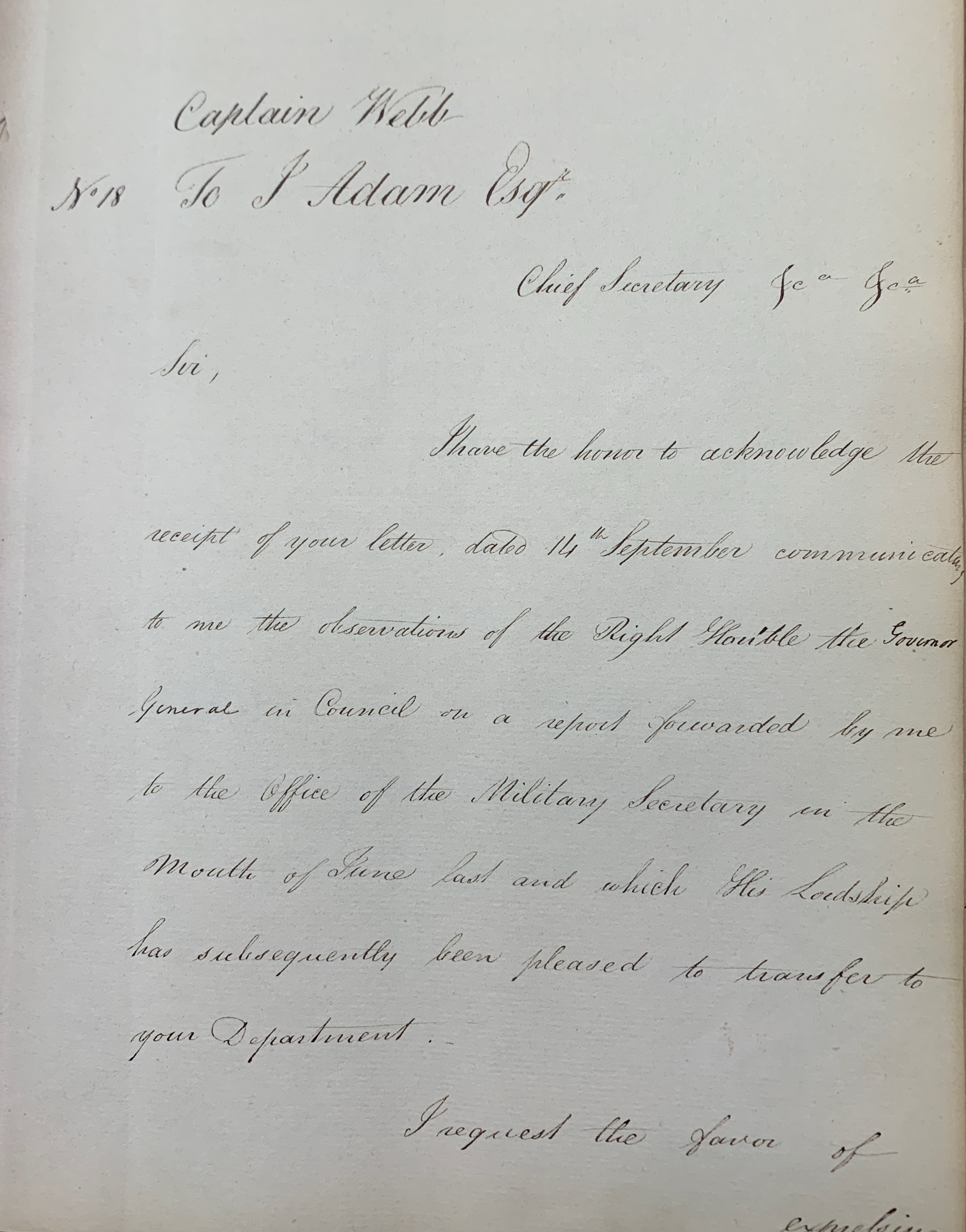

Webb’s response would normally have just required a short acknowledgment of the receipt of the letter from John Adam with an assurance that he understood all that was said in it and would rigorously adhere to the instructions given. His letter does indeed open by saying all that was appropriate but goes on to say that before the letter arrived he had already become involved in activities which the letter directed him to avoid. He explains:

Not aware of the wishes of Government previous to quitting Bootan, I became in some measure a party in a transaction which the receipt of your letter occasions me to regret,but though totally ignorant of the nature of these occurrences which have rendered necessary the precaution you mention, I should hope that there cannot possibly arise any evil from the circumstances which are hereafter detailed. Some time ago Mr Traill, [SC Note: The recently appointed Commissioner for Kumaon] not from any suggestion of mine, sent to me several proclamations addressed to the Merchants of Ludak and Cashmire which stated that having received information that during the Govt of the Rajah of Kumaon, the parties addressed where in the habit of occasionally cavorting with Merchandize to Almora which intercourse had been interrupted by the line of policy adopted by the Gorkha government. The purpose of this proclamation was to convey intelligence, that the events of the late War had placed the Merchandise provinces, including between the Kalee and Sutlej rivers under the British authority for protection, and that the existing government offered every security and Encouragement to those who were disposed to renew the ancient intercourse.

Mr Traill requested me to forward the above by any convenient means and at the same time placed it my discretion to keep back these papers if it appeared to be likely that they could in any way prove offensive to the Chinese authorities.

Webb sent the papers to Tuklakot with a trusted person but goes on to explain:

The Deba had desired me to write to him occasionally and I sent a letter with a briefing present by the same opportunity. The letter in addition to compliments contained only that I had reported to my Govt that an Interview had occurred between us which had occasioned much satisfaction and that from our newspapers, I judged that a British ambassador had arrived in China and that it would be fortunate if such a general state of affairs should result as might enable me to visit him at Tuklakot at some future period.

The snows have commenced at so early a period of this year, that is highly probable this Messenger may not have found it practicable to accomplish his journey, but when I receive intimation I shall think it’s my duty to submit the particulars of the result to government and I have now felt it necessary to trouble you with the preceding detail.

Given that one of the highest aspirations of the EIC was that “Merchants of Ludak and Cashmire” would resume direct trading with Hindustan, it was not surprising that John Adam’s letter acknowledging this letter expressed warm words for Webb’s action, as well as confirming full recompense for the gifts given to the Deba.

Sir,

I am directed to acknowledge receipt of your letter of the 18th ultimo in reply to the instructions of the 14th September.

Your proceedings as reported in that letter are considered to be marked with great judgement and discretion and are entirely approved by his Excellency the Governor General in Council.

His Lordship in Council is pleased to pass the amount of the charges incurred by you on account of presents and Mr Traill will be authorised to pay to your receipt the sum of Rs 309.8 on that account.

Fortwilliam

16th Nov 1816. Signed J Adam Sect to Govt

The final letter in the file by date is a short covering letter to the Board of Directors in London

16 November 1816

On the proceedings of the annexed date is recorded a letter from Captain Webb employed in a survey at Kumaon enclosing an Extract from his Journal relating the particulars of a visit he paid to the Deba or Chief of Teklikot, a Chinese officer subordinate to the Viceroy of Gurdone. This document will be perused by your Honourable Council with interest. We expressed our approbation of Captain Webb’s conduct which appears to have been governed by a laudable degree of prudence and caution. Adverting to the state of affairs on the Chinese frontier however and the expediency of avoiding any thing that might cause umbrage or jealousy to that Government we enjoined Captain Webb to postpone till he should receive a further intimation on the subject the prosecution of any researches beyond the Snowy Mountains and the maintenance of any correspondence with the officers or subjects of the Chinese Government in that quarter. Captain Webb has since returned to Almora and you will perceive from his letter recorded on the annexed date that his conduct continued to be regulated by the same discretion which had hitherto marked it.

At that point the file ends but the Board’s very short and to the point response to the heroic and highly productive work done by Webb is given in another file, IOR/E/4/695. It reflects the Board of Directors' deep obsession about not doing anything to upset the Chinese.

Political 12 Feb 1819

Visit of Capt Webb

To Deba or Chief of Ticklakot

We are gratified with the interesting extract from Capt Webb’s Journal containing the account of his visit to the Deba of Ticklakot. Such excursions from the jealousy of the Chinese Government must be very cautiously undertaken or they may be less likely to produce a beneficial intercourse than the occasion offences or suspicion amongst Viceroys less enlightened or liberal than the Deba of Ticklakot. We approve, therefore, of the restrictions you imposed upon Captain Webb.

Webb

Webb soon returned to his work fixing the northern and eastern borders of the newly annexed province. His requests to be given an assistant were finally answered at the end of 1818 with the arrival of a draughtsman, Robert Tate, who was especially useful in drawing maps. After five years of work, he produced the first of his two maps of ‘The Province of Kumaon’, one of them a sketch map. Neither showed an international border and both showed the whole of the annexed province. One of them showed the river which flows down from Limpiyadhura as the Kalee, but there is no suggestion of it being a border of any sort. Given all that is revealed in this file there is no logical basis to suggest otherwise.

My research for this article did throw up one interesting story about Webb. I discovered a paper written by Lachland Fleetwood, then of the University of Cambridge, in which he records that, “William Webb, for example, was rather put out to learn in 1816 that a friend had obtained from St Petersburg a publication describing his having crossed the Himalaya, ‘regardées comme inaccessibles’ but ‘par lesquelles on peut ouvrir une route par la Tartarie jusqu'en Russie. [‘regarded as inaccessible’ but ‘by which a route can be opened through Tartary to Russia’] The source quoted is a communication, dated 2 December 1817, from Webb to Colin Mackenzie, the Surveyor General of India, in which Webb conveyed to Mackenzie, presumably in strong terms, why he was so “put out” at hearing this news. [See Footnote 46 of article at this link.

I was fortunately able to make contact with Lachland Fleetwood who generously shared with me the following:

[NAI/SOI, DDn. 150, f27]

Webb to MacKenzie Dec 2, 1817

I am the more anxious on this subject for I know from literary friends in England that this survey has excited some curiosity there, and perhaps even beyond that country: as Mr Strachey procured from the Russian embassy, and forwarded to me from ‘Tibreez’ a number of 'Le Conservateur Impartial' dated March 11th and printed at St Petersburg, which contains the following paragraph:

‘Le captaine Anglais, Webb, qui parcourt le nord de l'Asie, a, dit-on, d’après des nouvelles de l’Inde traversé d'énormes chaines de montagnes courvertes de neige, regardées comme inaccessibles, et par lesquelles on peut ouvrir une route par la Tartarie jusqu'en Russie.’

[The English captain, Webb, who is travelling through the north of Asia has, it is said in news from India, crossed enormous mountain chains, covered in snow, considered to be inaccessible, and through which it is possible one can open a route through Tartary to Russia]

Obviously there was an earlier part to this communication in which it seems Webb expressed concern [I am “the more anxious”] but the obvious question is what is “this subject”? It would seem from what immediately follows that the subject is his survey and his worry seems to be that details in it seem to be becoming available to a wider public. Webb wrote his letter to John Adam covering the extended extracts from his diary on 14 Sep 1816. It was replied to on 16 Nov 1816. So the dates fit an assumption that Webb is understandably ‘anxious’ about people leaking the details from his diary. [Lachland Fleetwood has a very interesting looking new book ‘Science of the Roof of the World: Empire and the Remaking of the Himalaya’ on the verge of publication.]

On William Webb, these words from the book A Mountain in Tibet by Charles Allen strike just the right note on the life of an outstanding public servant and the sad way in which his career in India came to a close:

“At the end of 2016 the report of his survey work in Kumaon was read before a meeting of the Asiatic Society of Bengal in Calcutta. Webb had computed the heights of nearly all the highest peaks in his area and when these were given there were exclamations of disbelief. He had provided the first scientifically based evidence to support Henry Colebrook's claim, made 20 years earlier, that some of the Himalayan peaks could be as high as 26,000 feet above sea level. Among the 130 heights that he gave was one for Peak XIV, now better known as Nanda Devi. Webb reckoned it to be 25, 669 feet high which is just twenty four feet higher than today's estimate.

Three years later he completed his survey of the Kumaon frontier by making his way past Niti village to the head of the Niti pass - but no further. It must have been a sad moment for him. For most of those five years he had worked without the assistance or companionship of another survey officer. “I am absolutely in a state of banishment” he wrote plaintively in one of his letters. “It is now half a year and upwards since I have seen a European face, and but for correspondence I should run no small risk of forgetting my own language.”

In 1821 the Surveyor-General retired and the selection of his successor began. William Webb believed himself to be a strong contender for the post, but to his great dismay the appointment went to John Hodgson, his junior by several years. For Webb this was “the total destruction of my hopes”. Declaring that the promotion of Hodgson over his head appeared to “attach some stigma to my professional character”, he sent in his resignation, which was accepted.”

In January 1822, William Webb handed over his maps and the field books of the Kumaon survey to the new Surveyor-General and sailed for England and a retirement, without receiving any honour or preferment for the outstanding work he did for Lord Moira and the EIC in amassing a host of new information about the state of trade over Britain’s new northern frontier.

We can only speculate on whether his meeting on Lipu Lekh with the Deba and his declaration about the strong bond of respect they forged with each other cast a cloud over his future career prospects. Perhaps it was the strong feelings he expressed in his letter to Colin Mackenzie, complaining about the leak of sensitive information which led to the article in the St Petersburg magazine. Maybe he was perceived as being too strong a character, and of not being a safe pair of hands. We will never know but we can hope that his retirement was a happy one and that he was long able to regale his friends about the three days he spent on Lipu Lekh in conversation with “the Deba or Chief of Ticklakot, a Chinese officer subordinate to the Viceroy of Gurdone.”

As with information analysed from ‘the Nepaul War papers’ in my earlier article, the detail in this file definitively refutes the notion that Lipu Lekh was some sort of afterthought by Lord Moira in the campaign to occupy and annex Kumaon, rather than being a central driver for the whole war plan.

With the acquisition of Garhwal and Kumaon, Britain had for the first time achieved, after many years of trying, a frontier which gave it direct contact with Tibet and with land under the sovereignty of the Chinese emperor, and the prospect of profits from the trade that would follow. No one named in the 70 pages of this file, from Lord Moira through the Deba to the zamindars, had the slightest doubt that this new British frontier included Lipu Lekh. The Sugauli Treaty had been formally signed three months before the meetings and from this time on, the EIC indisputably controlled the pass and the southern approaches to it, as subsequently did the British Crown and, after 1947, independent India. Administrative records and the accounts of many British citizens who travelled through the area during the period of British control, testify to that fact.