Longreads

76 MIN READ

Using extensive documentary footage from the Maoist conflict, General Sam Cowan provides incisive analysis on the military effectiveness of the People’s Liberation Army.

Foreword

I am delighted that my article analysing the strengths and weaknesses of the armed wing of the Maoist party, the People’s Liberation Army (PLA), is now available on The Record and particularly as it comes just after the recent 15th anniversary of the signing of the Comprehensive Peace Accord (CPA) which formally brought the conflict to an end. It also comes just in the midst of the Maoist party’s General Convention, currently underway in Kathmandu. As I make clear later in this introduction, the current party, under the name of the Communist Party of Nepal (Maoist Centre), bears little resemblance to the Communist Party of Nepal (Maoist) that fought the 10-year civil war and won 220 seats in the April 10, 2008 elections to become the single largest party in the 601-member Constituent Assembly. The following month, the new assembly voted to declare Nepal a democratic republic, thereby ending the monarchy, and on August 15, it elected the Maoist leader Prachanda, by name, Pushpa Kamal Dahal, as prime minister. His stock, and that of the party he leads, has fallen a long way since those days, and not just in popularity, as this article highlights.

The article had a long period of gestation. I began researching it after the signing of the CPA on November 21, 2006. The study focused on a number of videos shot by Maoist journalists attached to the PLA’s western division, using small hand-held cameras. Early in 2007, they became widely available and I managed to acquire a number of them through a journalist friend. Starting my work after the signing of the CPA meant that I was able to include in the analysis what I learnt from discussions with senior military sources from both sides which confirm, and in some cases amplify, what is seen and heard on the videos.

The videos I had were in no particular order and at first it was very difficult to make sense of them. I eventually concentrated on six of them that covered three significant military actions in the last year of the conflict, two of which had significant political consequences. The period covers the culmination of the feud between the top two Maoists, Prachanda, the party chairman, and Baburam Bhattarai, his recognised number two, which came close to splitting the party. It also covers their subsequent reconciliation and the start of ‘the Delhi process’ which led to the first formal political deal between the Maoists and the political parties. All these developments are seen impacting on the military actions covered by the 22 clips from the videos included in the article. I believe my study makes an important contribution to understanding an important aspect of a crucial period of Nepali history.

An earlier shortened version of the article, ‘The lost battles of Khara and Pili’ was published on Sep 2, 2008 in Himal Southasian. Doing more work on the material enabled me to produce this much more comprehensive version, which was first published, after peer review, in 2010 in the European Bulletin of Himalayan Research, No 37:82-116. A version of the same article was published as Chapter 9 of the book Revolution in Nepal: An anthropological and historical approach to the People’s War, edited by Marie Lecomte-Tilouine. The article was also published as a chapter in my book, Essays on Nepal Past and Present.

The original article, at Footnote 1, included, as this one does, hyperlinks to three YouTube links to view the 22 videos I worked on, grouped around the three military actions described. The article included, again as this one does, an appendix which gives a full translation of what is said in the clips. However, in this article for The Record I have given a separate link to the 22 videos which are all highlighted by number in the text. There is a short description at the start of each clip together with subtitles in English. I am grateful to Marie Lecomte-Tilouine for inserting them. They are a great aid to those who do not understand Nepali or the particular dialect spoken as the body language is important in a number of the clips. [For ease of reference, the link to the clips is given below, just above the introduction.]

I am most grateful to my friend and brilliant translator, Hikmat Khadka, for working with me over a long period, first, to identify which parts of the various videos would be most useful to me and, second, to do the translations of what is spoken on the clips.

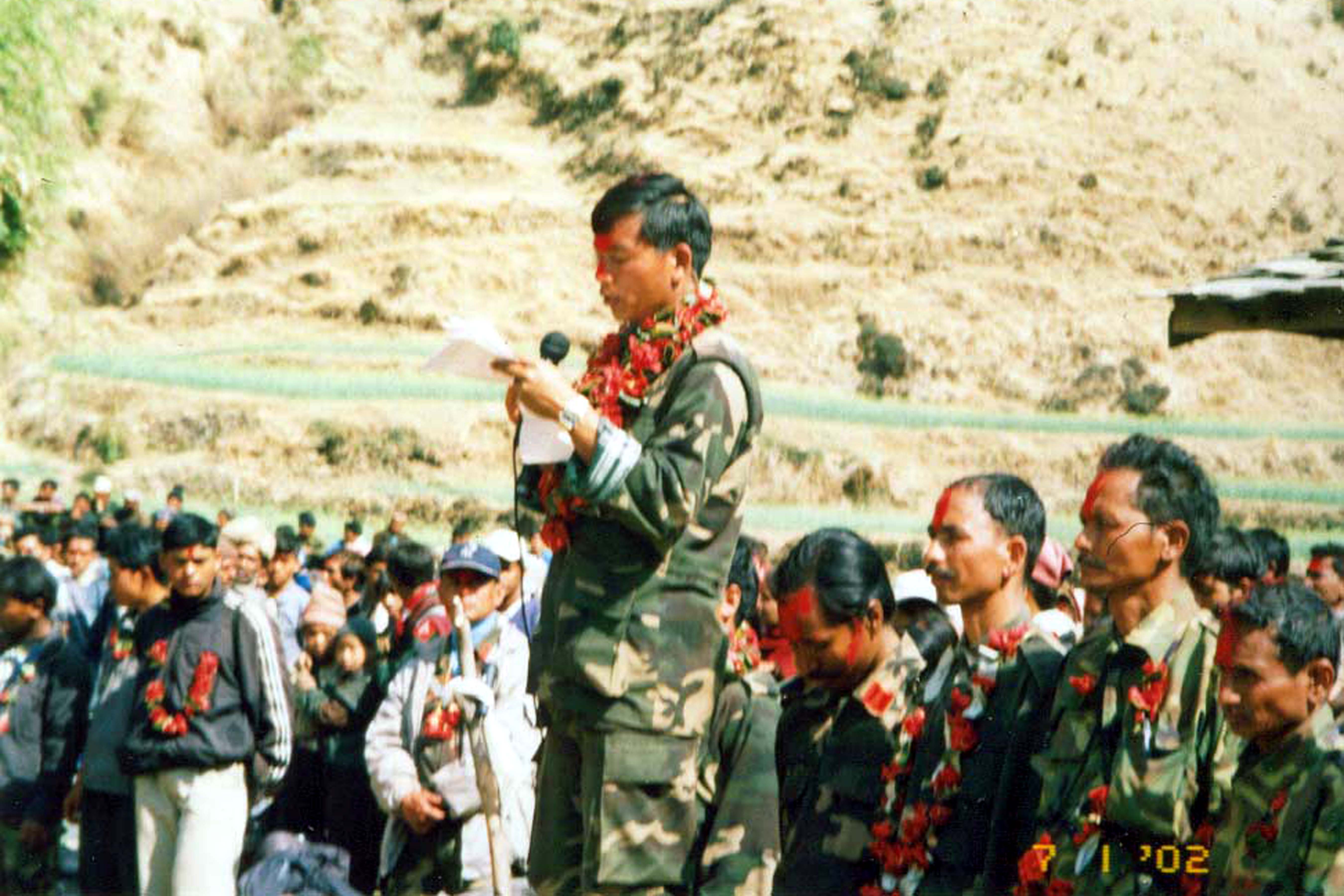

For those who would quibble over the title of my article, I would simply say, please examine the photos and the video clips. The thousands of young people you see did not come from a faraway land. They are all proud citizens of Nepal. You will also observe that all of Nepal is there, male and female, with every caste and ethnic group represented. Whatever weaknesses the PLA had, ‘inclusiveness’ was most certainly not one of them. Indeed, as an armed force, it was one of its greatest strengths. It is my contention that what is seen and heard in the videos shows that the PLA combatants were not simply blinded by ideology or driven by it. As with soldiers everywhere, they were vulnerable to demoralisation, appreciated the practical and tactical importance of sound plans, and knew that success in combat depended ultimately on martial qualities such as strong discipline and brave junior leadership. They suffered extreme hardship, and died and were wounded in their thousands, fighting for what they believed would be a better and more equal and inclusive Nepal.

They proudly served in what they called the Janamukti Sena, the army of the people, fighting against what they believed to be another army that represented a state which, when not oppressing their communities, was totally uninterested in doing anything to help them. That their political leadership subsequently abandoned them and every political principle they once claimed to hold is another story altogether but it is a good reason for giving this article, and the video clips inclusive to it, wider exposure now as they vividly highlight the scale of the gap between the hopes and aspirations of the young people who feature in the video clips and their betrayal by rapacious political leaders. It is a further tragedy that this betrayal extended well beyond those who served in the PLA or were members of the Maoist Party at the time. The dominant performance of the Maoists in the April 2008 elections showed that millions of people across Nepal, while disapproving of the armed insurgency the party initiated, fervently shared in the hope of the fundamental changes the party leadership promised.

In conclusion, on military effectiveness, I conclude that on balance, as a guerrilla army using the tactics and strategy of the form of warfare set down by Mao, the PLA performed highly effectively. It lacked the capacity to move successfully to the level of conventional war, but there can be little doubt about the significance of its central achievement in fighting an army armed to the teeth by India and the US to a strategic stalemate. It is not surprising, therefore, that the CPA, reflecting the ground reality of strategic stalemate, spoke of ‘the armies of both sides’, and that the Agreement on Monitoring of the Management of Arms and Armies treated the two together in such key areas as UN monitoring, while at the same time making specific provisions to reflect the continuing singular role of the army of the state.

It is worth recording that two of the PLA leaders featured in this article have made successful transitions to political life. Nanda Kishore Pun, ‘Pasang’, who features in one of the key Khara clips, is the current Vice President of Nepal and Janardan Sharma, ‘Prabhakar’, who features in a number of the Khara and Pili clips, is the Finance Minister in the current government.

DISTURBING CONTENT WARNING

Some readers will be disturbed by the images on Video Clip 11 and the photo which appears below the paragraph that follows it. They show images of mortally wounded Maoist combatants during and after the Khara battle. After a long discussion with my editor, we felt it necessary to include these images as part of the documentary record as they reveal an essential part of the story where words fail. I elaborate on that in the lines below the photograph.

***

Inside the People’s Liberation Army: A Military Perspective

Introduction

Much has been written about the Maoist conflict in Nepal, which lasted from 1996 to 20061, but little that gives objective insight into the basis of the military effectiveness of the armed wing of the Maoists, the People’s Liberation Army (PLA)2. This analysis is based mainly on a study of six Maoist-produced videos which cover an ambush that went badly wrong at Ganeshpur on 28 February 2005 and two significant battles that took place at Khara (on 7 April 2005) and Pili (on 4 August 2005). Ganeshpur is notable for the loss of an elite group of PLA fighters, including a particularly popular PLA commander, in a botched military action, and the consequent impact on morale. The Khara and Pili battles are notable for their significant political consequences, as well as for the fact that the two commanders-in-chief were personally involved in the instigation of deeply flawed plans that led to humiliating disaster and significant loss of life. Both sides, therefore, have a continuing strong vested interest in drawing a veil over what happened in these battles and why. The period covers the culmination of the feud between the top two Maoists, Prachanda, the party chairman, and Baburam Bhattarai, his recognised number two, which came close to splitting the party. It also covers their subsequent reconciliation and the start of ‘the Delhi process’ which led to the first formal political deal between the Maoists and the political parties. All these developments are seen impacting on the military actions covered by the videos. The analysis is also based on discussions with senior military sources from both sides which confirm and in some cases amplify what is seen and heard on the videos3. I have also applied my own experience as a professional soldier for forty years and a knowledge of Nepal gained over many visits and extensive trekking since 1965.

The videos I have studied first became available to selected journalists in late 2006. They were shot by Maoist journalists attached to the PLA’s western division, using small hand-held cameras. It would appear, not least from the candour of what is said in them, that initially they were intended primarily for internal use for analysing military actions, and very possibly also for recording for posterity the contribution of the PLA to the Maoist struggle.

The videos provide a singular insight into the military capability and internal dynamics of the PLA. No commentary is provided: the people seen on the videos, from senior commanders down to the most junior ranks, speak for themselves, often in the most candid and critical terms. A feature of them is the use of revolutionary songs as background music. These songs are an important part of Maoist culture, recorded on cassettes, written in song sheets and distributed widely: the melodies are based on the evocative folk songs of Nepal and have an immediate appeal4. Some are lyrical ballads and some, as on these videos, are much more martial.

Two particular songs are frequently used. The first is ‘Lamo Bato’ (‘Long Road’). The chorus refrain is ‘A long track of a thousand miles begins with a single step’ and typical verses are:

He who loves the people wins,

He who loots the people loses.

He who can win over death drives the world,

He who can enjoy gunpowder can exist in every fierce battle.

Bodies fall before the bullets, but confidence never does,

Physical remains degrade after death, but ideology never does.

The second song is ‘Hami Rato Manche’ (‘We the Red People’). The constantly repeated chorus is ‘We the red people, the people of People’s Liberation’ and typical verses are:

We can swallow fire, we can dry the ocean,

We are the people who were created from the martyrs’ blood,

We are the people who go on destroying the enemies’ forts.

We are the people who go on hunting for the people’s enemies,

Making earth and sky tremble, causing wind and storm to blow,

Chewing up the hearts of feudalists and imperialists.

These brief extracts illustrate a strong ideological drive centred on notions of sacrifice, violence and contempt for death. I leave the interpretation of such songs within a Hindu cultural context to anthropologists, but it is my contention that what is seen and heard on the videos show that the PLA combatants were not simply blinded by ideology or driven by it. As with soldiers everywhere, they were vulnerable to demoralisation, appreciated the practical and tactical importance of sound plans and knew that success in combat depended ultimately on martial qualities such as strong discipline and brave leadership.

In sum, the action on the videos provides a reasonable means for assessing the PLA’s fighting effectiveness: its strengths and weaknesses; the state of its training; and the quality of its people, particularly at the crucial leadership level of company, battalion and brigade, which has seldom been publicly exposed. Although there are few images of actual fighting, not least because most attacks took place at night and the obvious danger to the journalists, the videos also provide an opportunity to judge the quality of the PLA’s battle procedures, a military term of art covering all the complex processes necessary to launch a force into action in good order at the right time and place. These range from the giving of orders, to logistic support, to the movement, usually over many days, to (using conventional military parlance) an Assembly Area near the objective, and the subsequent insertion and correct positioning of assault formations in a Forming Up Point (FUP) prior to crossing the Start Line at H Hour, the time given for an attack to begin.

The strategic context and Maoist strategy

The PLA and its opponents, the Royal Nepal Army (RNA), fought two very different wars. Essentially the RNA fought a conventional war of attrition in which the emphasis was on the control of key territory such as urban centres and district headquarters, and on inflicting casualties through military engagements with the aim of weakening the Maoist will to fight, through a gradual exhaustion of physical and moral resistance. The PLA fought the war guided by a fundamentally different concept of conflict, as set down in the writings of Mao Zedong which in turn reflect many of the ideas of Sun Tzu who, 2500 years ago, drew on an existing corpus of Chinese ideas and practices in formalising his theory of war. Sun Tzu focuses on the need to manipulate the enemy to create the opportunities for easy victories and on lulling the enemy into untenable positions with prospects of gain, then attacking when they are exhausted. He stresses that avoiding a strong force is not cowardice but indicates wisdom because it is self-defeating to fight when and where it is not advantageous (see Keegan (1993: 202) and Sawyer (1993: 155)). This emphasis is reflected in a number of Mao’s best-known military maxims: the enemy advances, we retreat; the enemy camps, we harass; the enemy tires, we attack; the enemy retreats, we pursue5.

At the strategic level, Mao’s concept of ‘protracted people’s war’ is his most enduring legacy. He stressed that at all times the revolutionary army must stay unified with the people among which it fights. The people can thus supply the recruits, supplies and information that the army needs, and can be politicised at the same time. In this way, the cultural and political structure of society can be transformed step-by-step with military success. Revolution thus comes about not after and as a result of victory, but through the process of war itself. Hence, Mao’s best known slogan: ‘Power flows out of the barrel of a gun (Keegan and Wheatcroft 1976: 209). Intrinsic to Mao’s ideas about protracted war is the need to establish base areas and liberated zones and also the need to move through the stages of strategic defence, strategic equilibrium and strategic offence.

So in Mao’s terms where had the conflict in Nepal progressed to in early 2005? The period of Strategic Defence in the People’s War was deemed to have ended with the completion of the Sixth Plan in February 2001. In a document presented to the Central Committee in February 2004, Prachanda claimed that the stage of Strategic Balance or Equilibrium was reached with the attack on the RNA base at Ghorahi in Dang in November 2001. The Maoists announced the launch of their Strategic Offensive on 31 August 2004 but declared a preliminary subphase of Strategic Counter Offensive (see Ogura 2008).

A framework for an assessment of fighting effectiveness

The above sets the context for analysing the performance of the PLA in the three military operations selected but, before doing so, it is useful to have a framework for assessing the effectiveness of any military force. British military doctrine6 usefully defines ‘fighting power’ or ‘military effectiveness’ as having three distinctive but related components: the physical, the moral and the conceptual:

a. The physical component is the means to fight. This requires that people be recruited and trained; and that weapons be acquired and distributed for them to fight with.

b. The moral component concerns the ability to get people to fight. Those recruited have to be infused with the warrior spirit and mentally prepared for fighting through discipline and by convincing them of the merit of the cause for which they are being asked to risk their lives. Getting people to fight also involves the key area of motivation. This follows from high morale, but also depends crucially on maintaining a strong sense of purpose, a key task of commanders at all levels. A vital element of the moral component is leadership—the projection of personality and character to get soldiers to do what is required of them, whatever the difficulty and danger. Skill in the techniques of leadership is the foremost quality in the art of command and contributes very largely to success at all levels of war.

c. The conceptual component can be described at one level as the thought process behind the ability to fight. It is often based on ‘military doctrine’, not in the sense of providing rigid rules to follow but in establishing a common understanding of the approach to war that can be followed by all commanders from top to bottom. In short: this is how we fight. This component also emphasises the importance of effective command and the centrality of psychological factors in war, whatever its level of intensity, reflecting Clausewitz’s view that ‘all military action is intertwined with psychological forces and effects’ (von Clausewitz 1984: 136)7. In other words, war in all its manifestations is as much a mental as a physical struggle, and is fought as much with brains as with force. This struggle of opposing minds lies at the heart of strategy, the art of which is not to apply force on force but to employ strength against weakness; what Sun Tzu memorably described as achieving a situation where one is ‘throwing rocks at eggs’ (Sawyer 1984: 187). To achieve the concentration and surprise necessary to do this, a successful commander must read his opponent’s mind while disguising his own intentions. He must also minimise the potentially destructive effects of Friction, a term Clausewitz used to describe the host of factors that work against the successful implementation of any military plan. In this specific context, Clausewitz said, ‘everything in war is very simple but the simplest thing is difficult’ (von Clausewitz 1984:119 ). Size is a critical factor: the larger the force the more difficult it is to control, particularly when things go wrong. Hence the importance of experienced, strong willed commanders, a well-practised chain of command, the proper delegation of authority and responsibility, and reliable channels of communications.

In assessing the military strength and effectiveness of any force, full weight must be given to all these factors.

Ganeshpur

In late February 2005, the PLA’s western division was deployed in the Tarai to carry out an attack on Gulariya, the district headquarters of Bardiya district, about three miles from the Indian border. This plan was aborted because of fears that it had been compromised but, rather than withdrawing immediately to the relative security of the hills, a decision was made to mount an ambush in the Ganeshpur area on the main road connecting Gulariya with Nepalganj, the headquarters of Banke District, about 25 miles to the west. The ambush was carried out on 28 February 2005. While withdrawing, the ambushing force was surrounded by forces of the RNA and suffered heavy losses. The 37 PLA fighters killed in this action included Jit, the Brigade Commander of Second Brigade, an elite PLA formation designated as ‘the mobile brigade’. A further sixteen PLA people in a blocking position were also killed.

‘Jit’ was Prembahadur Roka from Dhyar village, near Ragda in Jajarkot. He was a legendary fighter of renowned bravery who had taken part in many Maoist attacks since the start of the People’s War, including the major assaults at Dunai in September 2000, Holeri in July 2001 and Mangalsen in February 2002. He was also a key commander in the successful attack on a RNA Ranger battalion in the forest area of Pandaun in Kailali in December 2004. Just two weeks before his death he had led the attack on the prison at Dhangadi in Kailali which had released 150 prisoners, over half of them Maoists.

The statement issued after the action by Prabhakar, the commander of the Western Division, pulled no punches. It showed in stark terms how scarred the Maoists were by the mauling they received:

We consider this incident very serious. The human and logistical losses have seriously affected the Western Division….. having given serious thought to our shortcomings in our analysis and synthesis of the comprehensive situation of that particular battle, we have to embrace the fact that we must advance through many sacrifices to turn the negative to positive8.

As divisional commander, Prabhakar must have authorised Second Brigade to carry out the ambush but Vividh, the vice divisional commander, was jointly responsible with Jit for the ill-conceived and badly executed plan which had such disastrous consequences.

Video Clip 1 is a short extract of a starkly realistic and insightful appraisal of what went wrong from a wounded combatant. In essence, he says that they were committed to the plan, and had the spirit to carry it out, but failed to understand that the enemy could discover what they were going to do. They also failed to observe his movements. They were still on the last plan. The plan was weak by being over-focused on attack. There was no plan for all-round defence when the enemy attacked them. Later in the video he says that the loss of their group leader left them devastated and that even when they broke clear there was no one to direct them.

Given all he has been through, his stoical and very articulate comments are impressive, and reflect well on his training as a PLA fighter. He concludes his analysis by saying:

Although we may be wounded or suffering due to physical pain, we hold a spirit to give all our blood and sacrifice our lives for the Party. In that spirit of sacrifice, we are proud of the (wounded) situation we are in.

However, the body language of those around him indicates a degree of demoralisation, and this is more manifest in Video Clip 2. What is seen and heard vividly demonstrates that, whatever might be claimed in Maoist poems and songs, the PLA, like other military forces, was not immune from the fact that casualties can hit morale hard, particularly the loss of popular and well respected leaders, and particularly their loss in ill-considered and badly executed actions. It is the job of commanders to deal with the consequential damage to morale.

On the videos Vividh is shown addressing two different groups of clearly demoralised fighters. To the first group, shown on the clip, he says that only Jit has been lost and that the party has many more commanders. He appeals to those listening to come forward bravely and aspire to be commanders. His acknowledgement of the impact of Jit’s death, and his effort to use his reputation and sacrifice to inspire those he is addressing, are common features of both talks. To the second group, not shown in the video extract, he says:

Together we must move forward, and we must become Jit. The common goal of every member, commander and commissar of this brigade has to be: ‘I want to become Jit.’ How to become Jit? This is the main issue. This is a beautiful and selfless goal, one that is filled with courage and wisdom. You and I must fulfil that goal.

Aside from ideological references, most military commanders would be very satisfied to give talks of such quality to soldiers who are in the state we see them in. The body language of many of those listening is not very responsive or encouraging but, given the searing experience they have been through, that is what one would expect. They all know the commitment expected of them when they became soldiers in the PLA: in Vividh’s words, at that point they signed their own death certificates.

Despite the imagery, it is a moot point how much this obligation, with its stress on the merits and value of sacrifice, differs from that of professional soldiers down through the ages. One distinguished soldier and academic memorably described the obligation as ‘an unwritten contract with unlimited liability’ (Hackett 1983), and the universality of remembrance rituals and the names and tributes on war memorials in every town and village in the western world attest to the near universal recognition of the value and honour placed on sacrifice.

At the practical level, Vividh assures his listeners that ‘a careful and detailed analysis’ of the action will be carried out. This echoes Prabhakar’s reference to ‘an analysis and synthesis’ to identify ‘shortcomings’. Nothing is known of the extent of this investigation or if anyone was held personally to account for the disaster. What is known is that just 39 days after the Ganeshpur action, despite Prabhakar stating that ‘the human and logistical losses have seriously affected the Western Division’, the division was part of a large force that attacked the RNA base at Khara, on the border between Rukum and Rolpa. Some elements of the division did not take part in this attack, including Vividh, the vice divisional commander. The reason for his absence, with others, can only be speculated on, but the setback at Ganeshpur must have had some impact on the morale of those from the western division, particularly from Second Brigade, who did take part in the Khara attack.

Assessment of the Ganeshpur action

The action shows the massive advantage the RNA had in tactical mobility over the PLA in the flat lands and good roads of the Tarai, and the effective use it could make of these. It also showed the tactical and operational naivety of senior PLA commanders, amounting to recklessness, in not appreciating the dangerous position their force was in, and not just because of much inferior tactical mobility. The RNA knew exactly what the Maoists were going to do, yet all too obviously the Maoist commanders had no awareness of RNA movement and positions. The inevitable result of this massive disparity in mobility and intelligence was the human and logistical losses referred to by Prabhakar in his statement. Jit and other key fighters were among the human losses, but equally significant would have been the psychological damage to confidence and morale which are key ingredients of effectiveness in any fighting force.

Background to Khara

The PLA first attacked the RNA base at Khara in May 2002. It was repulsed, with over 150 Maoists killed. It is hard to understand why the Maoist high command thought that it could succeed with another attack just two years later, knowing that the RNA had greatly strengthened the Khara fortifications. The video footage (Video Clip 3) shows the base to be well sited on high ground, thus requiring any attacking force to fight uphill through minefields and elaborate barbed-wire obstacles, all capable of being covered by machine-gun fire. The fortifications also included a layout of well-prepared trenches and bunkers. One infantry company and one engineer company, about 250 men, occupied the base.

A conventional military assessment would have indicated that an attacking force would need a strong opening bombardment of artillery and mortars, perhaps supported by air strikes, to weaken the defences before assault forces could be launched with any chance of success. Even with such preparation, however, the attacking force itself would still need strong superiority of firepower to succeed. The Maoists enjoyed none of these advantages, and the lessons of previous failed attacks should have been clear to them. In November 2002, they had failed to overcome the strongly prepared RNA positions at Khalanga in Jumla District, a setback that the Maoists subsequently acknowledged to have been a turning point in the war, and one that required a serious downscaling in their aspirations for overall military victory (see Ananta 2008). In March 2004, the PLA likewise failed to overrun the RNA defences at Beni in west Nepal, and Khara was a much tougher objective.

Information on Khara is very difficult to come by. The battle has now been written out of Maoist history, and no member of the party is prepared to talk about it to anyone. So why did this attack go ahead? Why the sensitivity and the collective amnesia about it? The answers are rooted in the bitter dispute between Prachanda and Bhattarai, which came close to splitting the CPN (Maoist) in late 2004 and early 2005. Much is known about this feud because, as part of the reconciliation deal, all their acrimonious exchanges were published at the time on the Maoist website.

The dispute came to a head in January 2005, when a politburo meeting demoted Bhattarai, his wife Hisila Yami, herself a prominent Maoist activist, and a few other key supporters, to the level of ordinary party membership. They also had restraints placed on their movement and outside communications. This dispute had a long history and many facets, but from early 2004 one key issue had begun to dominate. For some time the Maoist leadership had known that there was no solely military way forward towards seizing state power. As indicated by Ananta (2008) this truth had most likely dawned on some leaders as early as the setback at Khalanga in Jumla two years earlier. All eventually came to agree that an alliance was needed, but the two sides remained divided over whether it was to be with Nepal’s political parties, facilitated by India, or with then King Gyanendra and his army. Baburam Bhattarai crystallised the division starkly when he characterised his opponents as ‘those who consider feudal despotism as more progressive than capitalistic democracy.’9

We now know that in late 2004 Prachanda was involved in direct talks with personal representatives of Gyanendra. There was the prospect of an imminent meeting between the two and it is alleged that the carrot being dangled before Prachanda was the prime ministership. Then came the body blow of 1 February 2005, when Gyanendra launched his coup and seized absolute power. Journalist Bharat Dahal, in an August 2007 article in Nepal magazine (Dahal 2007) asserted that this action led directly to the decision to launch the Khara attack:

The timing of action against Baburam coincided with the time when Gyanendra seized power. To Prachanda, all the doors to the palace, India and Baburam were closed. He prepared a draft of the attack on Khara in order to prove his ‘brilliance’. The Party’s huge armed forces were mobilised for the attack, but the plan failed miserably.

This allegation could hardly be more damning—that Prachanda chose to attack the strongly held Khara position to show that, despite what Baburam Bhattarai and his supporters were saying and the hard lessons from past battles against well defended positions, there was a military way forward to seizing state power. The evidence from the videos shows the allegation to be soundly based.

The Khara battle: The start of conventional warfare

Prachanda committed both the PLA’s western and central divisions to the Khara attack. Video Clip 4 shows some of the PLA crossing the Bheri river and marching through the hills on the way to the assembly area for the attack. The considerable logistic challenge of moving and feeding thousands of people across long distances in the terrain shown is not dwelt on in the videos. The two songs used as background on this clip are ‘Lamo Bato’ and ‘Hami Rato Manche’.

In a briefing to troops on the march, Prabhakar, the commander of the Western Division, links the need for the battle directly to Gyanendra’s seizure of power, and spells out its extraordinarily ambitious aim, which is to open the door to final victory (Video Clip 5). He also gives a clear exposition of the reasons for moving from combatant warfare, and from the stage of strategic balance, to one of strategic counter attack: the alternative was ‘to allow our base areas to be demolished and all the people there to be massacred and destroyed’. He says that revolutionary transformation of the party was needed to escalate the war and that the party is now moving forward by being integrated and centralised—a reference, surely, to Baburam Bhattarai’s demotion.

All brigade commanders and commissars interviewed before the battle make it clear that this battle marks the move away from mobile/ combatant/guerrilla warfare to morchabaddha yuddha or conventional warfare; in sum, a test of strength between Prachanda’s and Gyanendra’s armies. All are fully confident about victory in the battle, and about its aftermath. All echo the theme of digbijaya abhiyan — a campaign of conquest.

The first question asked of Jiwan, the Third Brigade commander, (Video Clip 6) is very significant in pointing to Prachanda’s direct and personal involvement in making the plan and defining its aim: ‘In the words of Chairman Prachanda, you are in a campaign which leads up to the campaign of conquest. How have you taken this moment?’ His reply is a clear confirmation of the assumption in the question. He is in no doubt either about the expected domino effect that will follow success. He says that now: ‘We will launch attack after attack. We will achieve success after success. We will destroy the enemies’ forts, and now we will probably advance by sweeping away the enemy.’

The same optimism radiates from Bikalpa (Video Clip 7), the Eighth Brigade vice commander, and this answer again points to Prachanda as the prime mover behind the plan to attack Khara: ‘Our Chairman has a dream, which is very much linked to reality. That dream relates to victory, we have a dream to advance through Digbijaya Abhiyan…..We have an aspiration to open that door to conquest.’

Confidence in the plan and the chances of victory are vital prerequisites to success in war. One can only speculate about how it was that battle-hardened Maoist military commanders got themselves into such a delusional state of mind, but it is clear that Prachanda personally convinced them of the need for the battle, that it could and must be won, and that success would open the way to final victory.

The final orders for the attack were given round a large model built to represent Khara’s features and defences. Impressive as it is, it is one-dimensional and the earlier video views of the actual Khara position show how inadequately the model represents the difficulties of attacking it. Pasang, the Central Division commander, was given overall command for the operation. His orders start with a ritual-like greeting to those present, reminding them that they have taken ‘an oath of your own deaths’. He goes on in more matter-of-fact language to echo imagery from the writings of Mao about becoming ‘a real new person in history’. In Video Clip 8 he produces further evidence about the provenance of the imagery of ‘opening the door to conquest’ and the higher purpose of the decision to attack Khara:’Let us take our revolution to that level, and let us really open the door to revolution, or in the words of the Chairman, let us ‘open the door to conquest’. It is with that commitment that we have fixed this target’. The clip also shows Pasang moving on to use the model to point out ground of tactical significance. His remarks sound more like general exhortation than detailed orders, though clearly the video gives only a short version of what he must have covered.

In the video, Pasang and Prabhakar are shown sitting side by side. The body language between the two is not good, particularly that of Prabhakar when Pasang is speaking. Prabhakar’s own contribution (Video Clip 9) is muted, to say the least. He opens with a rather off hand remark and gesture towards Pasang: ‘We also took some help. Comrade Pasang even attended a class and returned with some training’ before making some vague remarks about the history of the conflict up to this point. A later interview with Bikalpa hints strongly at major differences of opinion between the two divisions over the plan for the attack: differences that were apparently never resolved. To preserve the vital principle of unity of command, general military custom would have required the brigades of Prabhakar’s division to be put under Pasang’s command, with Prabhakar having no place in the command chain. In military operations, there must never be any doubt about exactly who is in charge; there can only be one overall commander and one aim, in order to ensure absolute unity and focus of effort. Any other arrangement risks confusion and disaster, which is exactly what happened to the Maoists at Khara.

Video Clip 10 shows elements of the lead assault groups moving from the Assembly Area towards the FUP on the afternoon prior to the attack. What is striking is the scarcity of rifles. In conventional military terms, those shown would be classed as engineer assault troops who will lead the attack to cut through the wire or to dig under it. Shots from this and other videos suggest that quite a few women were employed for this most hazardous of military tasks. Those seen with back packs will be carrying the ubiquitous Maoist socket bombs and others will be carrying pliers for wire cutting. The clip is also interesting for the confirmation it gives of how the PLA conducted such attacks. One survivor of a successful Maoist attack on a fortified Armed Police Force and RNA camp at Gam in Rolpa district in March 2002 describes it clearly and accurately:

We were sleeping peacefully. We were in a very small number and proved no match against thousands of Maoists, most carrying grenades and armed to the teeth. They were Terai-based people, Tharus and Kham Magars. These terrorists came in three groups. At first, there were those who hurled grenades and at their back, there were those who held guns in their hands. And after those gunmen, there were those who were trained in carrying the dead and the wounded. Among them were also groups of medics (Ghale and Dangi 2002).

The evidence from the videos confirms this description. No actual fighting is shown but there is a short sequence (Video Clip 11), which conveys the message that the attack started in darkness. An M-17 helicopter gunship is shown hovering over the position and there is a short sequence which shows some PLA dead and wounded near the objective itself, with one of the latter being treated for a serious wound. The clip is enough to convey just a little of the harsh reality of a battle of this intensity.

The PLA did well to achieve total surprise. During the previous three days the RNA had received reports of large columns of Maoist forces moving across Rolpa and Pyuthan, but the exact location of the attack was known only after it began. The attack was intense and came from all directions. The reserve water tank of the position, which was raised above ground, was hit at the start of the attack, draining away all the drinking water. The M-17 helicopters giving fire support to the defenders during the night gave a big boost to the morale of the defenders. Although the attackers were able to close up to the wire perimeter and dig in round the position in places, by dawn only one section of about ten people had managed to fight their way inside the camp perimeter; but only to a distance of 15 metres, and all of them were killed on the spot. No further penetration was achieved.

I am certain that these are the bodies of the Maoist fighters I refer to above who managed to fight their way into the perimeter of the RNA camp. Given the weak plan and the fact that the Maoists lacked the firepower to attack such a strongly defended position, I find it impressive that this small section of combatants reached this point before being killed, having crawled their way uphill under the wire for an extended distance while under sustained heavy fire. In conventional armies, such actions would have led to the posthumous awards of the highest bravery medals. However, the photo and the images in the clip do more than just convey an impression of the harsh reality of a battle of this intensity. At different times during the Maoist conflict it was fashionable in Kathmandu to hear claims being made along lines such as, ‘the Maoists back is now broken’. This was always a prelude to stressing that there was no need to open talks with them as a military solution was very close. This, of course, turned out to be hopelessly wrong. As I wrote in an article in Himal Southasian, (‘Nepal’s two wars’, February 24, 2006) which argued the urgent need for peace talks to bring the conflict to an end: “War is not metaphor. War is death, destruction, ruined lives, communities torn apart, children orphaned, women widowed and much more. All decisions and discussions about its utility should be guided solely by awareness of these harsh consequences, not by mind-sets protected from reality by soft words and platitudes.”

This need to save lives by ending the war urgently through negotiations was not something that hit me with the benefit of hindsight in Feb 2006. Just after I retired from the army, I had a one-hour private conversation with King Gyanendra in Narayanhiti Palace in November 2002, just after he had taken his first step towards seizing absolute power, which would prove fatal for the monarchy. No one else was present. At the meeting, I gave him my view that I saw no possibility of a solution by arms. Notwithstanding periodic tactical gains, neither side would be able to deliver a decisive strategic blow that would end in the capitulation of the other. The war would end the way such conflicts invariably ended; by the parties to the conflict sitting round a table and arriving at a political compromise.

In sum, I advised the King that he had to do a deal with the political parties, prior to holding talks with the Maoists, otherwise at some stage he would find himself isolated. This advice was not well received. In the end, with disastrous results for the monarchy, King Gyanendra decided to go it alone, relying on the assurances he was constantly receiving from the army, that the Maoists would be defeated militarily, and taken out of the equation. Such assurances reinforced the King’s already strong preference to avoid dealing with the political parties. This would clear the way for him to establish a version of his father’s Panchayat system, under a constitution that would be granted to the people by him, their sovereign, as his father and brother had done in 1962 and 1990. As in those constitutions, ultimate power would have remained in the sovereign’s hands. All of this was very clear from my conversation with King Gyanendra.

The RNA claimed that in follow-up operations it captured documents that showed that Pasang’s plan covered the contingency of renewing the attack the following night from the PLA’s dug-in positions around the perimeter, and there is evidence in the video that this was the case. The attack did pause at dawn and there was a subsequent loss of momentum. During the morning an M-17 helicopter can be seen landing about twenty men from a Ranger battalion as reinforcements (Video Clip 12). Their arrival gave a great boost to the morale of the surrounded defenders. Clearly it would have had the reverse effect on the morale of the attackers who had fought all night at such a high cost to achieve so little. It is significant that the video shows the time of this event as the point when the attack was called off. Some fifty PLA bodies were recovered from around the perimeter, but casualties must have been much higher. Some reports speak of over 200 PLA killed, with many others seriously wounded.

The attackers fought long and bravely against determined RNA resistance, but they lacked the firepower to achieve success against such a strongly entrenched and defended position. Other significant factors also worked against success. After the battle, two separate interviews with Bikalpa point to deep-rooted weaknesses within the PLA’s chain of command that prevented all possibility of victory.

In the first of these (Video Clip 13) Bikalpa indicates the depth of the difference between the two divisions over the plan for the attack. He says that at a meeting Prachanda ‘had made the spirit of the plan very clear to all comrades’ but that there was ‘a huge debate, a very long debate’ between the two divisions over the tactics to be used in this first battle of conventional warfare. He alleges that Pasang’s division did want the battle to be conducted over two nights, as the RNA claim the captured documents show, but that Prabhakar’s division argued that the battle should start in mid-afternoon, and that they should fight through the night and take the position by noon of the next day.

Irrespective of the merits of these two plans, after the battle, in Bikalpa’s second interview, given to some Maoist journalists, (Video Clip 14) he points to even starker reasons why the attack was doomed to fail; namely, glaring weaknesses in the PLA’s command and control arrangements during the battle, and confusion over the respective roles of the two divisions. He says that the western division’s main role was ‘to provide support’. He complains that the battle ended before some of the people under his command had been committed to the attack, generating real anger and even the threat of disobedience. This suggests that large parts of the western division were never committed to the battle. But his main criticism is more noteworthy:

There were many problems when we went to the battle. There were many weaknesses. As we analyse things, we have to bear the consequences of certain shortcomings. Things did not happen the way we had imagined they would because there was mischief and betrayal. Many things ended up deceiving us. Whose weakness was it the most? In clear and straightforward terms, it was the commander’s weakness. It was the main commander’s weakness and also ours.

An assessment of Khara

Bikalpa’s criticism of Pasang is unfair and misplaced. The fact that it comes from a brigade commander in Prabhakar’s division, and was filmed by a journalist attached to that division, simply confirms the suspicions expressed earlier, regarding rivalries and lack of unity of command. Pasang would seem to have done well to finish the attack when he did: throwing in more troops would simply have added to the casualties. This analysis shows that as well as lacking the firepower necessary to be successful at Khara, the PLA’s senior commanders lacked the training, experience and the means of communication to ensure that up to 4000 people spread across six brigades and two divisions could be used in a properly coordinated way that made certain that their combined potential was applied effectively to the point of attack. In sum, it was not simply a case that the plan was weak, or that any of the commanders or combatants were weak. The fundamental weakness stemmed from the assessment that the PLA was in a fit state, in terms of training, equipment, experience and command arrangements, to move from mobile or guerrilla warfare to conventional warfare, and carry out a complex deliberate attack on a position as strongly defended as Khara. The responsibility for this flawed judgement ultimately has to rest with Prachanda, the PLA’s Commander-in-Chief.

The final verdict on Khara is the simple, stark assessment of Ramesh Koirala, the Eighth Brigade Vice Commissar (Video Clip 15) ‘the truth is: we lost. In the words of our Chairman, we weren’t able to open the door of victory. It remains closed and padlocked. We couldn’t unlock that padlock.’

For Prachanda, the defeat must have come as a crushing personal blow. His much-proclaimed dream of ‘conquest’ was shattered. There was only one direction in which he could now turn. Within four weeks of the Khara attack, Baburam Bhattarai, still reduced to a position of ordinary party member, was in Delhi with one of Prachanda’s right-hand men, K B Mahara, to start the process that ultimately led to the agreement with the Nepal political parties in November 2005.

The Khara defeat left the Maoists’ military reputation bruised and battered but within a few months, ‘the feudal autocrat’ in Kathmandu would order a deployment of his army that would give the PLA the chance to regain its lost prestige and to acquire over 200 modern weapons and large amounts of ammunition and explosives.

The background to Pili

On 24 July 2005, a mix of pioneer and combat engineers, supported by an infantry company, began to deploy to build a camp on the steep-sided banks of the Tila River, a major tributary of the Karnali in the midwestern Kalikot District. The purpose was to establish a base from which to resume the building of the Surkhet to Jumla road. The decision was taken at the direct behest of Gyanendra. By this time his credibility as an effective ruler was sinking by the day as the Maoist insurgency spread and strengthened, and as most development activities stalled. To boost his public reputation, he decided that decisive action was needed and in early July 2005, at the height of the monsoon, he ordered his army chief immediately to resume the building of the Jumla road.

The likely consequences of obeying this command should have been spelled out to Gyanendra. Instead, the order was merely passed on, and the soldiers were dispatched to build a camp in what the RNA official spokesman, Brigadier General Deepak Gurung, later described with excessive candour as ‘a strategically unfavourable place’.10 A second report quoted him as saying that ‘the temporary security base at Pili was not an ideal location. The decision to set up the base there was a technical one, not a tactical one. We didn’t expect our workforce to bear such an attack.’11 It was a massive dereliction of duty not to have done so, not least in its disregard of one of the most important dictums of war: never underestimate your enemy. Grainy, long range video footage of the camp (Video Clip 16) shows that the camp was built into the side of the hill with the dominating ground on the ridge above left unoccupied, leaving it hopelessly vulnerable to any attack which came from that direction.

The Maoists heard about the RNA deployment on 2 August, ten days after the first soldiers arrived at Pili. Prabhakar was with the Second Brigade at Dashera village in Jajarkot, 70 km southeast of Pili. Vividh, the vice-divisional commander, was with the Third and Eighth Brigades in Turmakhand village in Achham District, 70 km directly west of Pili but on the other side of the Karnali river, preparing to carry out an attack on Martadi, the headquarters of Bajura District. As soon as the PLA commanders heard about the Pili camp they decided that it would be an easy target and should be attacked as soon as possible.

Initially, Prachanda was reluctant to give his approval. At the time, CPN (Maoist) representatives were already in Delhi in consultation with the political parties, and a ceasefire was imminent. Prachanda clearly could not risk going into these negotiations on the back of a reversal on the scale of the failed Khara attack. His commanders assured him that success was guaranteed. The key commanders involved agreed that their forces should set off immediately with the aim of concentrating the division’s three brigades at Raut hamlet, near Pakha village, just one hour east of Pili, during the early afternoon of 7 August.

PLA preparations

Before each major attack, the PLA held a ‘coaching’ day (the English term is used) to finalise preparations and to enable commanders to brief subordinates. Video Clip 17 shows such a briefing of company and battalion commanders of Second Brigade by Prakanda, the Regional Bureau-in-Charge. Prabhakar has spoken before him, telling those assembled that they have good intelligence about the Pili camp, that it is still being constructed, and that the fortifications are ‘not something which had been constructed after years of hard work’ and that ‘the bunkers are made of wet mud, not cement.’ He stresses that, since the work is still going on, they have no clear idea of the defensive layout they will find when they get there; flexibility and improvisation will therefore be needed. Prakanda’s essential message is right on the mark: ‘In war, whichever side makes mistakes faces defeat. Our enemy has just made a big mistake, and we must move quickly to take advantage of it.’

Over 150 kms away on the same day, Vividh held his coaching day for the commanders of Third and Eighth Brigades in Badi Malika secondary school in Raskot Siuna village in Kalikot district. In his 20-minute speech he, like Prabhakar, stresses the uncertainty surrounding the defensive layout they will find when they get to the objective but expresses confidence that its incomplete state gives the PLA an excellent chance of victory. He gives no orders but discusses general tactics that might be used in the attack. He also gives clear indications that the party leadership is nervous about the attack, ordering them, ‘you are to return if you are not confident of success in what you are aiming’. Vividh says that the PLA has gone to attack too many places recently and has returned without fighting for various reasons, including nervousness among the top party leadership that ‘we must not lose on any account’. His main message is that this time ‘we must fight and win, whatever the difficulties’.

In Video Clip 18 Vividh makes a highly practical point on sacrifice which is perhaps not sufficiently stressed by academic commentators on Nepal’s Maoists:

The main thing is that we go forward at once. And although sacrifice is the main thing when we do this, we must not take the issues of arms, technology and the modalities of attack lightly. The history of the proletariat group has been such that it has captured the world through sacrifice of life. So if our sacrifice is in accordance with the right modalities, rules and procedures, such a sacrifice can be accepted more easily. But if there are flaws in our styles, procedures and processes, the sacrifice occurring under such pretext becomes a difficult one to accept.

This shows not a thoughtless and blind ideological approach to sacrifice but a highly practical consideration of what is required to make death in combat both worthy and acceptable.

Perhaps the most interesting parts of the Pili videos are the contributions that Vividh invites from the floor. Eleven unnamed commanders speak, probably of battalion and company level. These are the people at the heart of Maoist military success. It is a safe bet that they would not be in this room unless they had proved themselves in many actions, leading from the front in the style required by all successful military organisations. It is impossible to over-stress the importance of such leadership in war. None of the speakers dwell on ideology. All are clearly highly experienced battlefield commanders. They speak incisively, candidly and critically, often about lessons from past battles that have not been learnt or put into practice. Video Clip 19 shows just four of them.

The first speaker essentially says that attacks are failing because of a gap between the understanding of the plan beforehand and its practical application during implementation. Only by closing this gap will success come, he stresses. The second speaker makes this point even more starkly. He refers to Khara to highlight that if everyone has a different understanding of the plan beforehand, there will never be consistency in implementation. He underlines his case by asking a highly pertinent rhetorical question: before Khara everyone got the same coaching so why was there such variation in implementation? What is decided before the battle is not being implemented, he says.

The third speaker is emboldened enough to cast doubt over the move to morchabaddha yuddha or conventional warfare. He does not mention the phrase but his line is clear enough. After moving to the unique stage of strategic counter attack the desired results are not being achieved: ‘Therefore, let’s accept that we have not won. So if we are to return from this point, I would say that the party centre must reconsider the wargraph of the force’s counter-attack strategy. They should look back and trace any mistakes.’

The fourth speaker’s contribution is typical of many in highlighting practical lessons gleaned from previous attacks. His main point is that the PLA has limited arms technology so it is important to make the best use of what they do have. He highlights weaknesses such as wasting ammunition and throwing grenades to land outside wire perimeters rather than inside, and advocates the use of picking up and using discarded enemy arms and grenades as they fight through positions.

The approach march and battle

Getting to the objective on time required the three brigades to do a five-day forced march with little food or rest on two different routes. The videos show that both routes were very tough going at the height of the monsoon, and with a series of 4000-metre ridges to be traversed. Second Brigade travelled in an almost straight line from Jajarkot. Third and Eighth Brigades first had to head northeast in order to cross the Karnali at the Jharkot bridge in Ramkot, well to the north of Manma, the district headquarters. They then came south over Chuli Himalaya to meet up with the Second Brigade at Raut village.

Video Clip 20 shows: the nature of the terrain over which Prabahakar and Second Brigade marched from Jajarkot; a short briefing which took place at midday on the day of the attack, in which speed and urgency is stressed; and the descent to cross the Tila river and the approach march to the objective along the north bank of the river. A helicopter is seen landing 300 metres outside the perimeter of the RNA camp just as the Maoists are moving into position to start the attack. There are also some long distance views of the camp.

The quality of the video drops dramatically at the start of the attack because of fading light and loss of lens focus, but the very short Video Clip 21 is worth particular mention because of what it conveys in such a short time. Shot just after the helicopter landed, it shows elements of Eighth Brigade preparing to take their place in the assault. At the beginning, the light of battle can be seen in the eyes of the two young women being loaded up with the packs carrying the socket bombs. The scene then shifts to show very young and thin people on the trail waiting their turn to be committed, wearing little so that they do not get their clothes caught on the wire as they dig under it or cut it. At the end, two young girls are seen with wire cutters, with two lads behind them holding digging tools to burrow under the wire. This clip again indicates that quite a few women were employed for this most hazardous of military tasks: breaching defences. As fighters, they would probably have had the highest casualty rate of all. In most armies many of them would have their chests covered in medals, including those for the most conspicuous bravery.

Prabhakar and Vividh met as arranged at 1 pm at Raut hamlet near Pakha village and agreed that H hour should be 6pm that evening. The PLA plan was basic in the extreme. Each brigade was simply given an arc of responsibility so as to encircle the camp and ordered to breach the fence perimeter and make the best progress it could into the RNA camp. Attacking from all directions was a sure recipe for a fair measure of chaos and confusion, as well as increasing the risk of inflicting casualties on one’s own forces. The very loose nature of the plan and the other factors mentioned would have put a very strong premium on dash, initiative, bravery and strong leadership at platoon and company level.

The attack achieved total surprise: this in itself is a massive indictment of the RNA’s security precautions. The landing of the helicopter distracted the defenders as they went to unload it. The Maoist commanders decided to take advantage of this opportunity, and the attack began at 5:45 pm, though probably by fire only at this stage since the main attack formations were not yet in a position to physically attack the perimeter of the camp itself. The video shows that Second Brigade was about an hour behind the other brigades in getting into position.

The Maoists quickly captured a number of unarmed RNA soldiers who had been unloading the helicopter, including, they claim, the commanding officer of the battalion, who had come to the helipad. The commander managed to escape during the subsequent confusion, and turned up two days later at Manma, along with 114 other men from the battalion who had also somehow managed to escape from the camp. Some evidence of their rapid exit and bedraggled state comes from an article by Tularam Pandey, the first journalist to arrive in the camp, just six days after the attack. He describes a scene of utter devastation. Along the trail from Manma to Pili, he records, ‘there were torn pieces of uniform, abandoned boots, caps and cartridges of bullets’. He also quoted villagers as recalling how the soldiers who escaped were ‘hungry and naked’, and that they gave the soldiers ‘food, clothes, shoes’.12

The RNA later announced that 227 soldiers had been in the camp at the time of the attack. There were probably a few more, since we know that 58 were killed, 60 were taken prisoner and 115 turned up at Manma. This means that about 120 soldiers stood their ground to resist the Maoists. The RNA drew a veil over who bravely stood and fought, and who did not. Bad weather prevented any air support from MI-17 helicopters. More than 3000 Maoists took part in the attack, so it was not surprising that RNA resistance effectively ceased after about two hours of actual fighting. The outnumbered RNA men, taken by surprise in a badly sited and unprepared camp, did well to hold out for so long. The turning point in the battle came when a seven-man section, which was part of the force that attacked from the unoccupied higher ground, overran the one General Purpose Machine Gun (GPMG) and killed its crew. This had kept the Maoists pinned down for some time. Five of the section were killed and the other two seriously wounded. After that it became, in military parlance, a case of mopping-up other isolated elements, no doubt in an environment of considerable chaos, which probably accounts for different claims for the length of the battle.

The Maoists were ravenous and totally exhausted, so their first action after the battle was to cook a meal from captured RNA rations. Most slept near the camp, though some remained busy destroying and salvaging RNA kit and equipment during the night, an activity that might again have misled some villagers about the actual duration of the attack. The first Maoists began withdrawing at six the next morning. By midday they had all left, having stripped the camp of all that was useful to them, and taking along sixty RNA prisoners. Over 70,000 rounds of ammunition of different calibre were captured, and among the Maoist weapon haul were: one 81mm mortar with 150 bombs, one GPMG, twenty Light Machine Guns, seventy INSAS rifles, and eighty SLR rifles. Video Clip 22 shows the weapons on display at a western division gathering that took place at Bhadam in Jajarkot five weeks later. The first RNA troops arrived at Pili from Manma at 11:00 am on 9 August, a full day after the Maoist withdrawal. Twenty-six Maoists were killed in the attack. The RNA prisoners were released to the Red Cross on 14 September.

The RNA at the time, and later, claimed that the defenders held out for longer than is described here, but just 26 PLA killed in an attack of this scale does not indicate prolonged and over-resolute resistance from what was a very well armed force. Maoist journalists writing for Janadesh, the Maoist news outlet, with memories of Khara to expunge, also had an obvious interest in exaggerating the length of RNA resistance and the strength of the defences. They wrote what I believe to be elaborate, largely fictitious descriptions of the attack, including claiming that the PLA had to endure attacks from MI-17 helicopters. However, given the direct personal connection of Gyanendra and his army chief, General Pyar Jung Thapa, to the debacle, it was the RNA who had the greater interest in distracting people from asking questions about who was responsible. It quickly became apparent that there was to be no question of acknowledging mistakes or of paying proper tribute to the soldiers who fought bravely under such disadvantageous conditions. Instead, their sacrifice was derided and disparaged in an attempt to cover up for gross incompetence and grave dereliction of duty on the part of the top brass. Not even the dead bodies of the soldiers were to be exempt from being put on display in a public relations exercise designed to achieve this nefarious purpose.13

An assessment of Pili

What cannot be disputed is that Pili was a total rout and a serious humiliation for the RNA. It was an object lesson in the disastrous consequences of underestimating one’s enemy. The outcome was a major boost to the prestige of the PLA and its military prowess, at a politically critical time for the Maoists. The PLA commanders and their soldiers deserve great credit for concentrating so quickly to carry out this attack despite the arduous terrain and difficult conditions they had to overcome. Their dash and skill achieved a situation of advantage akin to Sun Tzu’s ideal of applying strength against weakness, in contrast to what had been attempted at Khara. The weakness that was exploited stemmed partly from poor tactical decisions by local commanders in how they laid out the camp, but mainly from the incompetence and appallingly bad judgement of senior RNA commanders who allowed their soldiers to be deployed in such an exposed position without adequate protection.

The video covering the action amply demonstrates the particular strengths of the PLA. The combatants are shown to have levels of toughness, resilience and commitment that one looks for in the best of military organisations. Most striking are the personal qualities shown by the company and battalion commanders who spoke at Vividh’s coaching. Very few people from this group have ever uttered a word in public but their quality as soldiers and leaders shines through, as does their clear aptitude and very obvious enthusiasm for soldiering. As explained, the nature of the Pili battle would have put a premium on brave and innovative leadership at platoon and company level, and it is clear that those seen on the video measured up fully to what was required.

Overall assessment

So what is the overall assessment of the PLA when measured against the three components of fighting power listed earlier? On the physical component, the videos confirm that although the PLA was not short of manpower and could improvise logistic support to enable large numbers of combatants to move quickly across long distances in tough terrain, it was woefully weak in firepower. Large numbers of combatants did not have rifles, and machine guns and mortars were in scarce supply. Socket bombs and other home-made explosive devices could only compensate for this deficiency to some limited degree. This was one prime reason for the defeat at Khara, and would have been a lasting impediment to a successful escalation of their military effort to the level of conventional warfare.

The PLA also shows up moderately in the area of the conceptual component. Senior commanders were highly motivated and committed, and many of them had years of experience of fighting at company level, but understandably they lacked training and experience to command and manoeuvre brigades in a large contact battle. The communication means at their disposal was also inadequate for this purpose and Khara showed the inevitable outcome when unity of command is lacking and when there are no properly understood and well-practised procedures for the delegation of authority and responsibility. The escalation to morchabaddha yuddha ruthlessly exposed these weaknesses and was a grave error, as the young commander in the schoolroom pointed out.

On the moral component, the videos clearly show that the PLA scores impressively high against all the criteria listed: mentally prepared for fighting; belief in a cause; highly motivated; a strong sense of purpose; brave and talented leadership; and a willingness to put one’s life on the line, whatever the danger. These very great strengths helped to compensate for many of the other weaknesses identified. However, Ganeshpur showed that the PLA was not immune from the fact that severe setbacks and casualties can hit morale hard, particularly when those concerned can see that their commanders failed them. The crushing defeat at Khara also showed the grievous error of elevating this component as being supreme above all other considerations. Before World War I, the French and British generals committed the same mistake but, like the PLA at Khara, they learned the hard way, and at great human cost, that offensive spirit and high morale can only carry an attack so far when faced with the physical realities of barbed wire, well-prepared entrenchments, machine-gun fire and determined defenders.

On balance, as a guerrilla army using the tactics and strategy of the form of warfare set down by Mao, the PLA performed highly effectively. It lacked the capacity to move successfully to the level of conventional war, but there can be little doubt about the significance of its central achievement in fighting an army armed to the teeth by India and the US to a strategic stalemate (see Cowan 2006). In doing so it played a pivotal role in ushering in the momentous political changes seen in Nepal over the last 4 years.

Nearly four years after the signing of the Comprehensive Peace Agreement that brought the conflict to a close, the PLA combatants who achieved this impressive feat of arms still languish in UN supervised cantonments despite the agreement providing for a special committee to supervise, rehabilitate and integrate them. Would they make good soldiers in a conventional army? There was a clear ideological dimension to their training and culture but, on the evidence of the videos, the PLA knew that, at root, military success is fundamentally based on the unquantifiable but eternal martial qualities of leadership, discipline, courage, tenacity, willingness to endure hardship and danger, and ultimately to risk and if necessary sacrifice one’s life.

Bringing the combatants together with elements of the present Nepal Army to form a new army in Nepal would take time and considerable effort but with the right military and political will, and with the right investment in suitable confidence building measures, and as part of a total reform of the Nepal Security Sector, I am certain that it could be done, following patterns adopted in other parts of the world. All the provisos listed are important but the process will remain stalled until some political will emerges to make it happen. This seems further away than ever, as therefore does the prospect of consolidating peace and democracy in anything that remotely could be described as a New Nepal.

***

Footnotes

1 This article owes its provenance in part to a joint research programme funded by Agence National de la Recherche and coordinated by Marie Lecomte-Tilouine, People’s War in Nepal: An anthropological and historical analysis. The results of the programme were published in 2013 in a book under the same name. The present article is a chapter in the book. It was first published in the European Bulletin of Himalayan Research, Number 37, 2010. A link to it is given under References at the end. Relevant video clips, referred to in the text, can be viewed at <http://bit.ly/EBHRvideo1>, <http://bit.ly/EBHRvideo2> and <http://bit.ly/EBHRvideo3>. A YouTube link to the clips with English subtitles can be found here. Written translations and their numbers linked to the clips are given in the Appendix.

2 A notable exception is Kiyoko Ogura’s painstakingly researched and very graphic account of the PLA attack on Beni, the District Headquarters of Myagdi District, on 20 March 2004 (Ogura 2004). I am most grateful to her and to my friend Anne de Sales for the support and encouragement they have given me in preparing this article. Their respective singular and illuminating insights have been invaluable to me, although the views and judgments expressed are mine alone. I am also most grateful to David Gellner for his sustained encouragement.

3 I am very grateful to Hikmat Khadka for translating what is spoken in the extracts of the videos referred to in this analysis. The sound is of variable quality so there is room for doubt on some minor detail, but I am confident that the general sense of what is spoken is accurately conveyed.

4 See Stirr (2013), de Sales (2003), Lecomte-Tilouine (2006), Mottin (2010).

5 Mao’s prolific writings are summarised in various compilations of what is generally known as ‘the little red book’. His ideas, including the link with Sun Tzu, are well analysed in Griffith (1961), which includes a translation of Mao’s 1937 essay Yu Chin Chan (‘Guerrilla Warfare’). Griffith writes: ‘Guerrilla tactical doctrine may be summarised in four Chinese characters ‘Sheng Tung, Chi Hsi’ which mean ‘Uproar (in the] East; Strike (in the] West’. Here we find expressed the all-important principles of distraction on the one hand and concentration on the other; to fix the enemy’s attention and to strike where and when he least anticipates the blow. Guerrillas are masters of simulation and dissimulation; they create pretenses and simultaneously disguise or conceal their true semblance. Their tactical concepts, dynamic and flexible, are not cut to any particular pattern. But Mao’s first law of war, to preserve oneself and destroy the enemy, is always governing’ (Griffith 1961: 26).

6 Design for Military Operations – British Military Doctrine Chapter 4 Military Effectiveness. http://nssc.ge/cms/site_images/British_Military_Doctrine.pdf

7 See also, of many examples, on page 137—‘Military action is never directed against material force alone: it is always aimed simultaneously at the moral forces which give it life, and the two cannot be separated.’

8 ‘Indian Army Intervenes against the Nepal People’s War’ by Li Onesto, 30 Jan 2005 (Countercurrents.org).

9 Letter from Baburam Bhattarai dated 23 November 2004, published in Samay magazine on 6 January 2005.

10 ‘Defective weapons blamed for Pili disaster Kalikot debacle: a Post report’. The Kathmandu Post, 13 August 2005.

11 ‘Video footage shows gory images of slain soldiers, ‘Maoists violated int’l humanitarian law’: RNA’ (nepalnews.com report 12 August 2005.)

12 ‘Reporter’s diary from Pili’ by Tularam Pandey, Kantipur, 22 August 2005, as reproduced in Nepali Times no. 262, 26 August 2005.

13 See nepalnews.com report referred to at Footnote 11. Also Cowan (2008).

***

Appendix: Extracts from video clips cited

Video Clip 1 [Wounded combatant] 00.55

‘Comrades, on the question of the implementation of our plan in particular, our spirit was at its own height. For our part, we were committed to implementing the plan made by the Party. We had the kind of spirit that would have been necessary in order to implement that plan and to attack the enemy, in one way or another, as a tiger would do. And we maintained that spirit. However, we did not realise that the enemy could possibly discover our plan, or (let us say that) we failed to understand the enemy. We observed the enemy’s movement only from one side; and, like our Party, we failed to observe their allround movement. Neither could we make the Party’s plan an objective one accordingly. We did not watch the movement from the Gulariya side but followed the (same/previous) plan. While we even chased the enemy coming from the Gulariya side, we failed to look in all directions. Let us say that there was a planner’s weakness in this. Anyway, such a situation arose.’

Video Clip 2 [Vividh to demoralised combatants] 01.10

‘Comrades, at times of loss, incompleteness and inadequacy, we must find adequateness and wholeness. Only then can we go forward. We must bear this in mind. Therefore, we must not forget this, and we are together in this. Only Jeetji has been knocked down. Our Party still has many more commanders. Those who cannot become commanders shall not become commanders now. The coming steps shall determine this. Please be prepared. We shall recruit people from here itself. Come forward bravely, and together we shall proceed. We shall sit with all comrades for a careful and detailed analysis.’

Video Clip 3 [Scenes of Khara objective] 00.18

Video Clip 4 [PLA approach march: crossing Bheri; through the hills] 00.51

Video Clip 5 [Prabhakar’s orders on march] 01.59