Features

Culture

11 MIN READ

Sandwiched between Thamel and Indrachowk, Na: Gha Twaa, or Naghal tole, with its toothache deity and numerous dental practices, has long been a dentistry hub. But things are changing.

Tucked in between Thahity chowk and Baangemuda lies a small neighborhood that goes by the name Naghal tole, locally known as Na: Gha Twaa. Often treated as a commuter’s bridge between the Thamel-Chhetrapati areas and the Ason-Indrachowk side, the primary Na: Gha street is usually packed with hawkers, scooters, bikes, and the occasional motor car that’s made the grave mistake of entering old Kathmandu’s claustrophobic streets.

At first glance, this neighborhood is anything but interesting. It lacks the touristy charm of Thamel and the bustling economy of New Road. Instead, it has a faux-cobblestone road with large periodic craters. The street is filled with an unorganized mess of pedestrians, illegally parked two-wheelers, and periodic splatters of pigeon scat and red paan spit. One might even say that Na: Gha is the tried and tested definition of your average Kathmandu street.

But prod a little deeper, enter the right gallies and ask the right questions, and you will start discovering the true character that this little neighborhood – Ward 25 of Kathmandu Metropolitan City – hides behind its dusty and forgettable facade. From under the banality of its everydayness emerge intriguing accounts of familial professions, age-old heritage, and the ever-flowing stream of time and change.

For one, there doesn’t seem to be one answer to what Na: Gha really means. While some locals suggest that the word ‘na:’ means ‘iron’ in Nepal Bhasa, alluding to a history of jewelry shops and metal workers around the area, others believe that the name Na: Gha might have been given in a similar fashion to other neighborhoods around the area, such as Won: Gha (Indrachowk), Ten: Gha (Tengal), and Nhu: Gha.

Sixty-five-year-old Siddhi Ratna Shakya, a local who used to specialize in scripts for the Department of Archeology, believes that the origins of the name Na: Gha are a tad different.

“I believe that ‘Na’ carries two sets of meanings. The first being a rendition of the Sanskrit word ‘Nawa’ meaning new, and the second being a shortened translation of the Nepali word for nine, ‘Nau’,” said Shakya.

As Shakya and I enjoy a cup of masala tea at a small chowk within Naghal, he points towards the Naghal baha, a traditional Buddhist Newa monastery, and explains, “Legend has it there used to be nine ghaitos (larger copper vessels) at the Na: Gha baha. These ghaitos were important symbols of prosperity in Newa culture, which might be why the neighborhood ended up being named Na: Gha.”

Coincidentally, there also happen to be nine chowks with nine wells tucked within the tole.

However, another Na: Gha resident and a prominent Nepal Bhasa academic, Rita Na:gha Bhani disagrees with Shakya.

“The ‘Na’ in Na: Gha is followed by a bisarga (colon). This implies that this ‘Na’ means new,” said Na:gha Bhani.

As for the actual neighborhood and its people, many of those who know of Na: Gha know it for the relationship this neighborhood shares with dentistry in Kathmandu. Many locals even claim that the neighborhood was not just Kathmandu’s dental hub but was the very point where dental practices began in the valley.

In an interview, pioneering dentist Dr Basanta Bahadur Rajbhandari lends support to this claim, naming Asta Man Rajbhandari, a Na: Gha local, as the first to have started dental practices in the valley, serving during Chandra Shumsher’s reign.

Actually visiting Na: Gha lends further credence to this assertion. The neighborhood is riddled with dental practices. Every ten meters or so, you are greeted by signboards with large painted smiles that read, “Teeth fixed here.” There are even shops that showcase full sets of teeth and dental prostheses as specimens inside glass cabinets in their foyers.

In Na: Gha, dentistry appears to have been the occupational norm, far before modern-day dental standards even came into existence. Back in the day, much like any other occupation, dentistry was a skill passed down from parent to child. And while a formal education in dentistry was never considered mandatory, many practitioners would have spent their lives helping in and around their father’s dental shop, learning the trade from a very young age and taking over when they came of age.

Dheeraj Ram Rajbhandari is one of many Na: Gha locals born into these dental families. Rajbhandari, 51, makes up the third generation of dentists in his family. His clinic, “Family Dental Clinic”, was started over eight decades ago by his grandfather.

“My grandfather started our clinic while working as a dentist for Juddha Shumsher. Back then even a six-month training certificate from India was acknowledged as a substantial qualification. There were no dental clinics at the time, rather these businesses were referred to as shops and practitioners weren’t considered doctors but rather shopkeepers,” explained Rajbhandari.

Since then, the small shop gradually adopted modern-day standards and practices, but still continues to be based on the bottom floor of the Rajbhandaris’ ancestral home in Na: Gha. During all this time, the shop was passed from grandfather to grandmother, then father and his three uncles, and now to Rajbhandari. Even Rajbhandari’s two older brothers make a living as medically licensed dentists. Rajbhandari himself never went to dental school, but chose to diverge from his academic background as a satellite engineer to manage his family’s clinic and ensure the continued existence of his family’s legacy.

Rajbhandari holds onto the hope that he will be succeeded by his children and they will keep the family business going. That’s more than likely to happen as both his son and his niece are currently in dental school.

Further cementing Na: Gha’s age-old ties with dentistry is a deity called ‘Washya Dyo’ in Nepal bhasa, literally translating to the ‘Toothache God’. This deity looks nothing like the gods and goddesses in the many Hindu temples in the area. Washya Dyo is an idolless large piece of wood that protrudes out of the side of a building and into the street. This chunk is said to have been part of a tree that once had roots all over the neighborhood.

Local lore has it that if a person prays to the deity and then nails a coin into the wood, any and all dental ailments will go away. A few skeptical locals such as Rita Na:gha Bhani, however, say that nailing coins might have been a way to discourage thieves from pilfering money that had been offered to the gods.

Locals like Rajbhandari and Shakya do not know of any direct correlation between Washya Dyo and the numerous dental practices in Na: Gha Twaa but it would be safe to assume that the existence of such a deity certainly helped dentistry blossom into an occupation here.

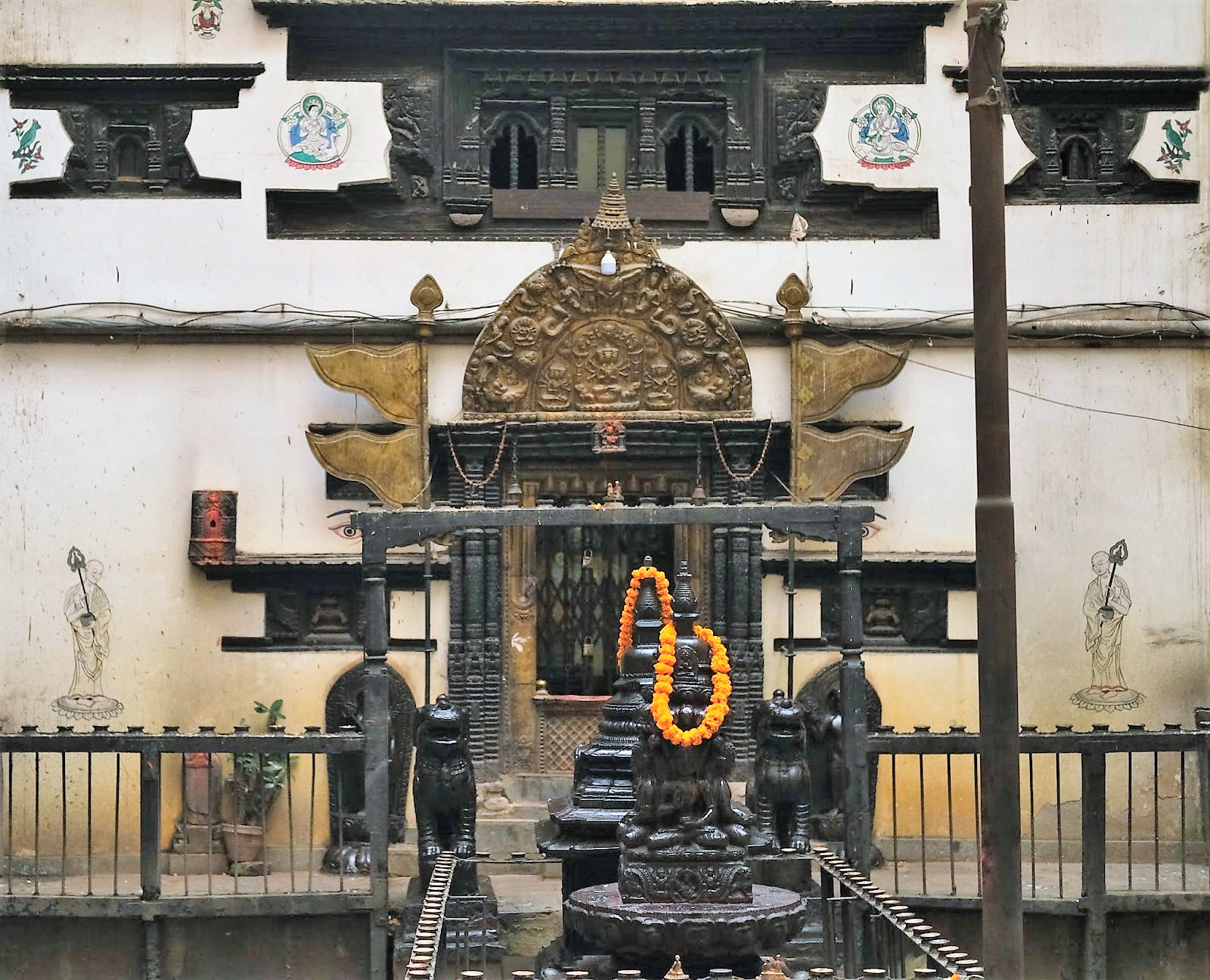

Dentistry and Washya Dyo are not the only pieces of history that exist in Na: Gha. Scattered across the neighborhood are dozens of historic heritages that have been determined to date back as far as the 6th century. A few key ones include the Nasa Dyo temple, the 9th-century Uma-Mahesvara sculpture, the 6th-7th century Kumar Sambhav (currently on display at the National Museum), and the iconic Shree Gha bihar.

Shree Gha, with its towering stupa, is also called the Kathesimbu, the Dharma Kirti bihar, and the Drubgon Tangchup Chueling Tibetan Monastery. Hidden some way from the main Na: Gha street, Shree Gha appears as a smaller version of the Swayambunath Stupa. American author Kerry Moran, in her 1996 Nepal Handbook, refers to Kathesimbu as a name that translates into “Swayambhu of Kathmandu.”

As to how such a massive piece of Buddhist architecture comes to exist in a neighborhood like Na: Gha, Moran mentions a fable that states that the stupa was originally from 5th century Buddhist India. A Nepali tantric was challenged by its builders to breathe life into it, which the tantric promptly did. The stupa is then said to have sprouted legs and followed the tantric to where it is today.

In more modern times, when buildings rarely come to life anymore, Burmese politician and Nobel laureate Aung San Suu Kyi is believed to have resided and studied Nepali and Nepal Bhasa at Shree Gha, also known as the Dharma Kirti bihar, during her second visit to Nepal in 1973-74.

Today, Shree Gha is more of a casual courtyard for locals to drink some warm chiya while basking in the winter sun. In the morning and evenings, school kids crowd street food vendors while robed Buddhist monks chant prayers inside the monastery; young lovers feed grains to flocks of pigeons and small groups of teens share smokes behind some chaityas.

Shree Gha is not the only part of Na: Gha that has changed. Over the course of time, the entire neighborhood has grown into something quite different from what it once used to be, both visually and culturally. While there are still a handful of traditional Newari homes scattered around the neighborhood, most ancestral homes in Na: Gha have been replaced by tall, skinny cement counterparts.

Rajbhandari, whose own home has gone through significant renovations through the years, says that it was a natural progression.

“Families got bigger, but the land stayed the same size,” he said. “The only choices people had were to either move out of the neighborhood or to reconstruct houses to be taller and have more rooms.”

But it is not just the physical structures that have transformed; the people too have changed. Subhan Kumar Shrestha, 61, a local who was born and raised in Na: Gha, shares that the neighborhood is no longer anything like the Na: Gha that he knew growing up.

“I don’t know anybody anymore. I don’t see a lot of the old locals around. I don’t even recognize the people at the chowk. Everybody seems to have migrated to other places,” said Shrestha.

Shrestha, who is also the immediate former ward chair, reminisces about days past when he and his friends would gather at the one house in the neighborhood with a television to watch football. He fears that with time, the tole is losing its strong sense of community.

“While many local families have moved out, the population of the tole has gotten denser. But despite this, as a community, it has grown farther apart,” he said.

Shrestha estimates that of the 4,500 to 5,000 people living in Na: Gha, only about 15 percent might still be ancestral locals.

As families expanded, people started to look for alternative places to live as the tall narrow houses of Na: Gha were less appealing as family residences, says Shrestha. And with old families moving out of the neighborhood, so did local businesses. Family-owned traditional ghee shops, Nepali paper shops, and goldsmiths that once covered Na: Gha street are now no longer in business.

“It was more profitable for families to close shop, move out, and rent or sell their houses,” said Shrestha.

This is even the case for dentistry, Na: Gha’s most cherished of professions. While Na: Gha continues to be the go-to spot for fixing teeth, Rajbhandari shares that only a handful of clinics have been here for long. Most old practices have long shut down.

“Time changes everything. It is not something where we get to say ‘we will’ or ‘we won’t’,” said Na:gha Bhani. “Instead of trying to avoid change, what we can do is remember our past and keep note of it while trying to make sure that the best values survive to the future.”

Sajeet M. Rajbhandari Sajeet is a Media Studies undergraduate and is currently reporting for The Record.

Opinions

5 min read

The Covid-19 pandemic, with its demands for physical distancing, brings with it an opportunity to reorganise and reshape our cities

Perspectives

9 min read

Reflections on one’s lowest to see what lessons can be learnt by the self and society.

Perspectives

Longreads

20 min read

Violence undocumented is violence denied, and new writing from Kalimpong and Darjeeling — which includes Chuden Kabimo’s Song of the Soil — is correcting this historical wrong.

Books

Perspectives

6 min read

Tim Gurung reflects on his journey of writing a book that traces the history of the Gurkhas, why he wrote it and the lessons we can take away from it.

Books

8 min read

A new book traces the history of Nepali tourism through encounters between Western travelers and Nepalis.

Culture

4 min read

During the many months of lockdown in the past two years, people revisited old hobbies or made new ones. Some discovered a love for baking and are still going at it strongly.

Interviews

11 min read

A 1963 interview with writer and critic Krishna Chandra Singh Pradhan

Features

5 min read

Being critical of the famous and wealthy can help rein bad behavior.