Writing journeys

8 MIN READ

In another edition of Writing Journeys, advocate Dev Datta Joshi reflects on the difficulties of schooling as a visually impaired person and how he came to see writing as a transformative tool.

Over the years I’ve worked with quite a few Nepali professionals on their writing skills. Dev Datta Joshi has been one of my favorites. Despite facing challenges that few of us will ever encounter, Dev ji overflows with good cheer. He also possesses a humility about his skill gaps and a hunger for learning that has made working with him a joy.

Dev ji grew up in the remote far western hills of Nepal. When just a little boy, a disease robbed him of most of his eyesight. Somehow, he persevered through various levels of school to become a lawyer. For many years, he fought hard and effectively to increase opportunities for blind and visually impaired Nepalis, and those with other disabilities. He likes to write, and has found publishing short articles a useful tool to advocate for disability rights. He describes part of his journey in this essay.

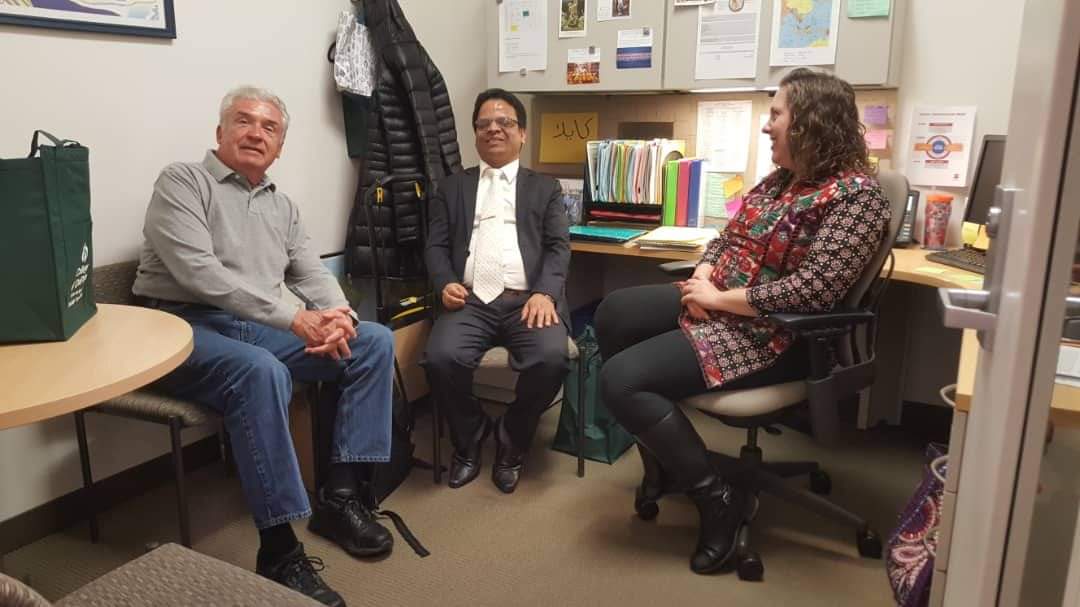

I got to know Dev when helping him with a fellowship application to study in the US. In that situation, not everyone is fun to work with. But Dev definitely was. He quickly grasped that my suggestions were not about the English language but about writing– about structure, clarity, and conciseness. He then worked hard to understand and address his weaknesses, without expecting me to do his work for him.

In his essay here, he mentions one of the challenges he faced in putting together that application: how to tailor it for American audiences who might not know a thing about Nepal or about disability rights or legal affairs. In addition, he had to explain a lot in very few words. Dev happily wrote and re-wrote, and then re-re-wrote and re-re-re-wrote his application until he got it where it needed to be. I was not surprised he got the fellowship.

Dev Datta Joshi is a leading expert in the area of disability rights, and has published extensively in the area. His focus is inclusive education, legal capacity, access to justice, and de-institutionalization of persons with disabilities. His publications include ‘Forgotten girls’ (Republica, December 17, 2017) and ‘Equality before the law’ (The Kathmandu Post, December 6, 2017). In 2018-2019, he was a Humphrey Fellow at American University in Washington D.C.

Writing Journeys appears every Wednesday on The Record. Click here for a roster of all the writers featured so far.

***

Powerful writing can transform society

I was born in Dadeldhura district in the Far West, one of Nepal’s poorest areas. There was no road. The society into which I was born faced illiteracy, poverty, malnutrition, and superstition.

When I was two years old, black fever (kalaazar) infected my village. I suffered its grim effects for three days. This disease stole much of my vision. At first, this did not cause me many problems, but the situation quickly deteriorated. I had to walk an hour to my primary school so traveling to-and-fro on difficult foot trails became much more dangerous.

Despite my poor eyesight, I excelled academically. I worked hard. My parents encouraged me. I used to read by holding books extremely close to my eyes even though eye specialists say that books should be at least 25 cm away while reading. Reading this way caused headaches, but I had no choice.

When I started primary school, fellow students and even teachers teased and bullied me. One day, my teacher wrote the classwork on the backboard but I could not write it down in time, so he scolded me harshly. I felt embarrassed. I burned with a sense of injustice. Events such as this left a deep imprint.

In grade seven, I became a district topper among 60 schools. I won a prize of Rs 500. I also performed well in quiz competitions, essay writing, and speech competitions. In college, I won prizes in academics as well as in extra-curriculars.

During my Intermediate in Science (I.Sc.) examination, a senior government official treated me poorly, questioning why I was holding the exam papers close to my eyes. However, I persevered and passed in the first division.

I wanted to be an engineer. Unfortunately, I had to abandon this as a result of my poor eyesight. I needed a support person during engineering practical classes to do instrument readings. I requested help but the administration did not provide it.

When I was young, I was fond of writing. I used to write on education, environment, and science and technology. While in school, I never got any ideas from teachers on how to draft an effective article. My primary and secondary school teachers gave priority to rote learning, which continues even today.

In rural Nepal, access to education is usually a pipedream for blind students. Blind students are ignored at school. Teachers know very little about how to help blind children. Many teachers and administrators think blind students can’t learn. For these reasons, in rural Nepal, many blind children don’t go to school at all.

Some parents do not send blind children to schools in order to protect them from discrimination and abuse. Also, especially in rural areas, schools don’t provide Braille and large print textbooks for the blind and visually impaired.

Education policymakers too are not aware of what inclusive education really means. As a result, illiteracy remains high among blind people. I have visited schools in Ireland, Canada, and the United States and spoken at length with teachers about how to ensure quality education for blind students. These countries provide reasonable accommodations to blind students such as support people, flexible curricula, extra exam time, and disability allowances. As a result, blind students can often lead fully independent lives and can reach the careers they want to become productive members of their communities. Even in Africa and Latin America, despite limited resources, little gap exists between an inclusive education policy and its practical implementation. But Nepal has a long way to go.

In 1996, in Dadeldhura, I established an audio library with accessible technology for blind people -- the first ever, not only in Nepal, but also in South Asia. The library has helped blind Nepalis overcome educational barriers. We have recorded -- in English, Nepali, Hindi, and Doteli -- thousands and thousands of printed books so that blind people can compete with their able-bodied counterparts. We have recorded books on history, geography, politics, general knowledge, and education. Nepali students now have access to the Ramayana, Bhagavad Gita, The Bible, Mahabharata, Swasthani Brata Katha, Shri Krishna Charitra, and books like Karnali Blues. With help from this audio library, thousands of blind people have secured employment and have completed their graduate studies. A few have completed doctorates.

I have published two books and more than 100 academic and newspaper articles, nationally and internationally, about disability rights. Sometimes, I write about corruption in Nepal. My writings have helped change public perceptions about persons with disabilities. While visiting Nepal’s remote areas, teachers tell me that they have read my articles in national daily newspapers. I have also received emails from Australia and Europe regarding my articles on disability rights.

In 2003, I won a lawsuit at the Supreme Court to ensure free inclusive education for over 90,000 children with disabilities. Back then, schools denied disabled children admission, taking away their right to education.

Nepal needs to do more to improve writing skills. Last year, I visited a few public schools in Kathmandu to learn about student writing skills. I asked grade 10 students to write a few sentences on girl’s education. But none of them could write even one sentence. They did not know how to start writing.

In Nepal, even university students do not know how to draft a few sentences of writing. If we look at Master’s and PhD theses, they seem the same. Students ‘copy and paste’. Sadly, in Nepal, most academic staff do not care about plagiarism.

To be honest, before winning a Humphrey fellowship to study in the US in 2017, I did not know how to draft an effective and simple essay. Before that, I did not think about the audience. I used to choose long words and long sentences. I did not know about clear formatting and strong verbs. Also, I did not know about paragraph structure. I’ve found Tom Robertson’s ‘Mitho Lekhai’ videos on writing skills to be instrumental to improve writing skills.

Effective writing plays a vital role in changing society. In a country like Nepal, where rule of law is weak, writing articles can help make Nepali citizens, government officials, and the international community safeguard the rights of vulnerable groups, especially rural, disabled people. I became a human rights lawyer to challenge disability-based discrimination, nationally and internationally. Writing well helps me do that.

Tom Robertson Tom Robertson, PhD, is an environmental historian who writes about Kathmandu and Nepali history. His Nepali-language video series on writing, 'Mitho Lekhai', is available on Youtube. His most recent article, 'No smoke without fire in Kathmandu’, appeared on March 5 in Nepali Times.

Interviews

12 min read

Vyathit was a prolific poet who wrote in Nepali, Newari and Hindi languages

Writing journeys

9 min read

Writer Amish Mulmi provides a running analogy for his writing in this week’s Writing Journeys, while also handing out sound advice on how to write well.

Features

The Wire

12 min read

News from 1953 about the turmoil in Nepal’s Terai still resonates today

Writing journeys

6 min read

This week on Writing Journeys, series editor Tom Robertson takes apart an older article of his, line-by-line, providing critical insight into what makes a good essay.

COVID19

Photo Essays

3 min read

Covid-19 forced Jaquir Mansuri to cancel his daughter’s wedding and delay his plans for retirement but the pandemic is not over yet and Mansuri has gone back to work.

Writing journeys

9 min read

Writer and educator Niranjan Kunwar reflects on his writing process and provides advice on how to make your words fly.

Perspectives

11 min read

The acceptance speech of writer Yogesh Raj who received the 2018/2019 Madan Puraskar for his historical fiction, Ranahaar.

Writing journeys

11 min read

This week in Writing Journeys, journalist and storyteller Chandrakishor writes about the value of learning new languages and using writing as a tool for social harmony.